If you judge just based on its trailer, Katana Zero appears to be a fast-paced, gory, stylish action game with a killer synth soundtrack and a heavy reliance on ‘80s action movie tropes. And it is all of those things, but it’s also smarter, funnier, sadder, and more careless with its mature themes than you might think. Katana Zero fails to provide any kind of content warning so here’s one: in addition to its frequent focus on mental illness, drug addiction, and withdrawal, the game also depicts suicide and violence against children. If you’re not comfortable with any of that, you may want to skip this one. But if you can deal with its clumsy handling of all sorts of sensitive subjects, Katana Zero may be worth checking out for both its sheer high-speed fun and its surprising complexity.

Another thing that’s clear from the trailer: Katana Zero owes somewhat of a debt to Hotline Miami, but not nearly as much as it might seem at first. Both games feature pumping synth soundtracks, high-stakes action, quick deaths and resets, and a protagonist on the verge of mental collapse, not to mention that they’re both published by Devolver Digital. The core gameplay loop is fairly similar as well: At the start of each stage, you’re given time to plan your approach, then you dive into a level full of enemies to dispatch and you don’t stop moving until either they’re all dead or you are. Outside of that, though, Katana Zero is a different beast altogether.

In Katana Zero, you’re always equipped with a sword, and you can pick up anything from bottles to smoke grenades to attack at range. You can also slow time with the push of a button, which allows you to ambush your enemies, dodge attacks, and even deflect bullets. It’s a relatively small set of options, but the game is constantly giving you new ways to combine them. At the start of the game, you’ll likely struggle against rooms with two or three unarmed opponents in them. By the end, you’ll be taking on entire SWAT teams with ease. The farther along you get, the more each level starts to feel like a puzzle to be solved more than a fight to win, and the best thing about it is how you can look for solutions on the fly. You can only slow time for a few seconds before stopping to recharge the power, but it gives you enough time to plan and pull off some really spectacular maneuvers if you use it judiciously. Knowing when to deflect or dodge gunshots, how to best attack from stealth, and how to use the environment to your advantage can turn an encounter that would be impossible in head-on combat into a swift, balletic victory. You might play a single encounter a dozen times until you get it right, but once you’ve figured out all the angles, you can turn an entire room full of gun-toting thugs into a fine pink mist in a matter of seconds. And at the end of each area, usually just a few interconnected rooms long, you get to watch a surveillance video of your successful attempt in real-time, without all the time-bending hijinx you used to achieve it.

Despite the basic loop staying the same throughout the whole game, Katana Zero never got old for me. When it ended (after five or six hours), I was satisfied, but could have easily played it for twice the time. That’s partly because the core of the game is just so fun, but also because it also continuously transforms by the context of each level. In some games, moving from a rooftop to an underground bunker might not shake things up to much, but Katana Zero’s focus on precise execution makes even small differences in level layout and enemy placement completely change the flow of an encounter. Some, but not all, stages also end with a climactic boss fight, which again shake up the formula in interesting ways. Rather than acting like a heat-seeking missile as you have through most of the levels, zooming inexorably toward your terrified prey, boss fights put you on the defensive. You have to study their patterns and make good use of your time-slowing abilities to both read and react to their attacks. You may die 15 times in one fight, but when you do, you’re immediately resurrected for another run. Just like the rest of the levels, your final victory against a boss may take a minute or less in real time, but that comes at the end of much more time spent trying and retrying, testing and adjusting, warping the flow of time until you know your enemy better than they know themselves. The final boss in particular is an immensely satisfying duel against a better-equipped opponent who refuses to play fair, calling on you to master your limited tools to win.

Although I had a blast with Katana Zero the first time around, it definitely lacks replayability. Since the game is largely about figuring out how and where to attack and honing the mechanical skills you need to win, your second playthrough is an entirely different experience. It’s still challenging at points, and still fun to tear through levels that once tripped you up, but it just didn’t hold my attention that same way. There are some rewards for going back through the game, though. Once you’ve finished it, you unlock a vault where you can equip upgrades for your sword by finding keys scattered throughout the game. These keys are hidden behind some fairly interesting challenges, and I only found 3 out of 5 in my playthrough. Some of the upgrades are purely aesthetic (and very cool), while others change the way your sword behaves in interesting ways. I only wish that there were more challenges after this point, because the way these swords tweak your behavior could make them really fun to play with if replaying the game weren’t already an easier experience. There is some hope there, as the developers confirmed in an email that the final door in this area will be unlocked by a future DLC release.

If that’s all there was to Katana Zero, it would be an exceedingly fun game; well worth playing, though you can finish it in a long afternoon. But there’s much more to the game than combat, and the parts outside of that make it much more interesting and much more complicated.

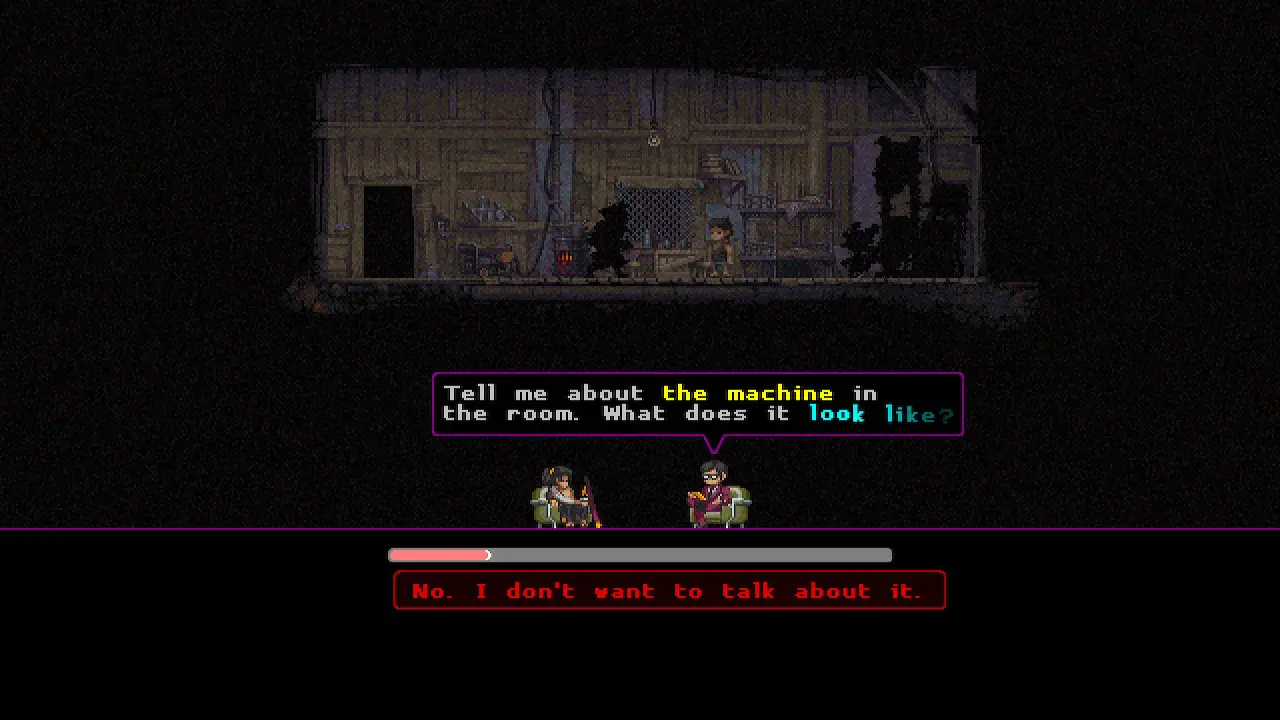

One of the coolest parts of Katana Zero actually has nothing to do with its combat. While it may seem from trailers that the game is mostly a series of combat rooms connected by cutscenes, you actually spend a fair amount of time navigating through non-combat story scenes. Between and during missions, your character (alternately called The Dragon or Zero) attends therapy sessions, has phone conversations, and talks to people in his apartment building and in the lobbies of hotels he’s been sent to murder someone in. Most of these conversations have actual dialogue trees that can affect how the game plays out in small but significant ways. Deciding when to lie, cooperate, or even interrupt the person you’re speaking to can change not just how characters react to Zero, but even how levels play out.

Alongside the unexpected amount of dialogue comes a story that’s surprising in a lot of different ways. First of all, there’s simply more focus on story than I would have expected going in. Katana Zero isn’t just an action with bits of narrative sprinkled in between levels. You actively play through story scenes that are every bit as important as the combat, lending context to what could otherwise be senseless violence. In these moments, Katana Zero often takes on a much more somber tone, a feeling that’s aided by its music, which switches from fast-paced synthwave to melancholy piano melodies as the scene dictates. The game is full of storytelling tricks that are genuinely compelling, to the point that I was often eager to get through its incredible combat just to reach the next story beat. While your actions can’t change the events of the story in many significant ways, you still need to make choices that propel it along, and those choices can radically alter the tone of the game. At other times, control is taken away from you, and you start to see that the story you’re being told might not be the whole truth.

I’m glad that Katana Zero takes its story seriously and has the guts to tackle more complex ideas than “you’re an assassin with a cool sword,” but this is also where my feelings get very complicated. One more warning is in order here: I’ll be discussing the sensitive content mentioned above and spoiling some of the story’s themes beyond this point.

The biggest reservation I had going in was the game’s use of therapy sessions as a plot point. While a lot of games have been getting better about depicting mental illness recently, the “homicidal maniac” trope is one of its most common expressions in games and in the ‘80s movies that inspired Katana Zero, and that seemed to be where this game was leaning. Levels in the game are punctuated with Zero seeing a psychiatrist for the PTSD he developed fighting a war in a thinly veiled Vietnam stand-in that’s only ever referred to as “the jungle.” He’s given a new assassination target and is administered Chronos, the drug that gives him his time-warping powers. There’s also some talk about people addicted to Chronos being willing to kill to get more.

These things seem to play into harmful stereotypes about mental illness and addiction, but in the context of the game, they’re at least a little easier to swallow. Throughout the game, you learn that Zero is the product of a military experiment using Chronos to turn him into a super soldier. Without a regular injection of Chronos, he’ll die. His “therapist,” while ostensibly working to reintegrate Zero back into society, is actually manipulating him, sending him to kill people who are aware of the government’s use of the drug. I thought this twist was ultimately successful, but its initial resemblance to some ugly cliches definitely put me on edge. In the end, the game isn’t attempting to make a statement about addiction or to realistically depict mental illness and therapy. Instead, characters in the game are using this imagery as cover for their manipulation of Zero. Still, some players will likely be put off by how much the game draws from outdated tropes.

A far more troubling aspect of the game is its repeated insinuations (and even depictions) of violence against children. A few of the most disturbing scenes can be justified in the context of Zero’s growth as a character, though they still seem needlessly graphic, but the most egregious one seems included simply to shock and it derails the game right at the end. Throughout the game, Zero forms a relationship with a little girl living in his building, which at first seems to help him start healing from his trauma. However, near the end of the game, the girl is kidnapped as a result of Zero’s actions, and a post-credits scene shows her captors discussing their plans to hurt her. It becomes clear that her role in the story was never as a character of her own, or even a way to show Zero’s humanity. Instead, she exists to be kidnapped and (presumably) rescued by Zero at some point. It’s an offensive scene that feels emotionally manipulative while adding nothing to the story. You can’t keep it from happening if you finish the game, the scene has no resolution, and there’s not even a sense of how Zero feels about it. It’s just a crass setup for a sequel that sours the ending. There are other threads left dangling that are also irksome just because they leave the story feeling half-finished, but none are as repellant as this one.

To be clear, I’m not saying that any of these subjects should be off limits, but they need to be approached with the appropriate amount of care, and not every game is the right venue for the discussion at all. Katana Zero has an interesting story it tell; it just doesn’t seem to have anything to say about any of the difficult subjects it brings up, and nothing about the game’s presentation prepares players for them. Zero can certainly be read as a victim being forced to kill to survive, and the disturbing plot about child abduction could be used to show his growing empathy, but the game never engages with those ideas. That reading is also undercut by Zero saying at one point that he actually just likes killing. And when the story is at its darkest, Katana Zero’s driving synth score, spectacular violence, and sense of humor seem at odds with its serious subject matter. The problem here isn’t that Katana Zero depicts PTSD, violence against children, or drug addiction, it’s that that depiction clashes with the game’s tone, and it uses them as window dressing without delving into their meaning or considering their context.

It’s a shame that Katana Zero makes these missteps, because it makes it hard to recommend what I otherwise thought was a phenomenal game without some serious caveats. My feelings about the game took a huge downturn right at the finish line, to the point that I might actually advocate just turning the game off once you beat the final boss to avoid some of its nastiest moments. Despite all my misgivings, I’ll be curious to explore Katana Zero’s DLC and planned sequel (also confirmed by the developers); I can only hope they find a way to change course and make the story they’re telling as interesting and thoughtful as the way they tell it.

Katana Zero

Great

Katana Zero is a game that I loved playing, but I walked away from it with some major reservations. On top of its tight, excellent swordplay, fun time-shifting powers, and pitch-perfect soundtrack, Katana Zero packs some interesting storytelling tricks that I wasn’t expecting. On the other hand, it uses its innovative structure to tell a story rife with ill-conceived takes on disturbing subject matter without a content warning in sight. Katana Zero is an extraordinarily fun experience for the few hours it lasts, but the bad taste it left in my mouth lingered much longer.

Pros

- Satisfying combat feels like a lightning-fast puzzle

- Soundtrack perfectly sets the game’s shifting tone

- Tells its story with an interesting dialogue system

Cons

- Fairly short without much replayability

- Relies on potentially offensive tropes and ends with a manipulative cliffhanger