Arcade games sure are cheap! That’s their general reputation, anyway. I’m not talking about their price here, but rather their tendency to lie, cheat, steal, and beat you down for your quarters. That gets expensive. Like any lovable rogue, however, arcade games remain appealing despite their penchant for thievery. Some arcade games are more fair than others, yet they all tend to lean on a sense of challenge to incentivize players to come back for more punishment. The truly dedicated players know that even the worst offenders contain tricks to learn and master in order to tip the scales in their favor – that’s what makes them fun.

Double Dragon Gaiden: Rise of the Dragons explores the balance between the scales of arcade difficulty. What exactly is the perfect balance between difficulty, mastery, and enjoyability? Rather than creating a game that definitively answers that question, Double Dragon Gaiden instead puts the solution into the hands of its players. It provides ample options for the individual to concoct their ideal arcade game experience. This experiment reveals that putting the power to tip the scales in the player’s hands comes at a cost.

One of the greatest strengths of arcade games is how easy they are to revisit. They typically focus on being easy to understand, immediately gripping, and ideal for short play sessions. Those core principles not only tempt people to give the arcade machine their quarters, but ensures that fresh quarters regularly cycle through the machine.

That well-oiled machine only works when it’s built upon a strong foundation. In other words, the game design being fun and engaging is the biggest motivator for wanting to continue to play it. Yes, it’s true: the best way to get people to replay your game is to make it good. Get out your notepad, because I have plenty more shocking revelations for you.

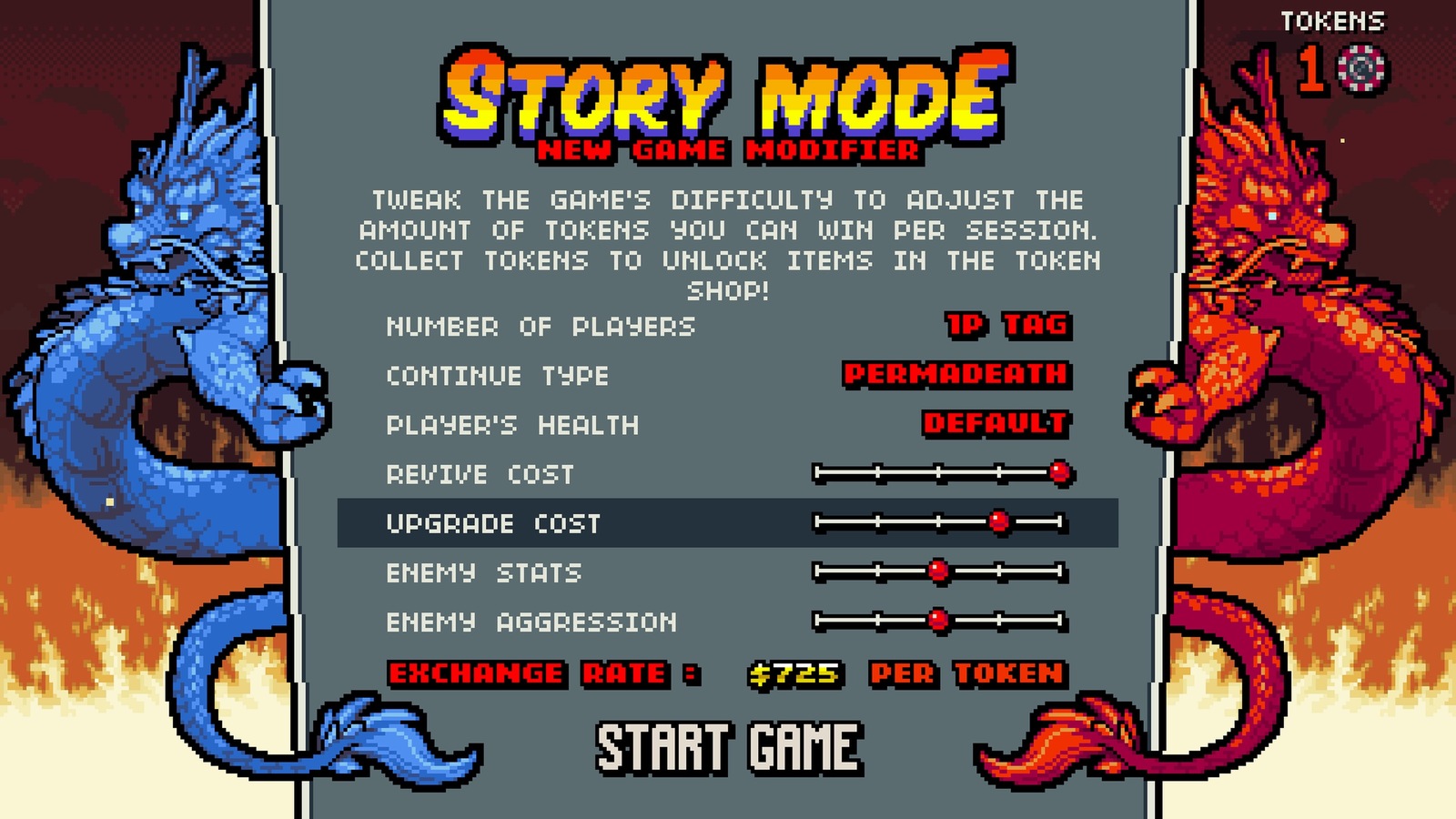

I bring this idea up because Double Dragon Gaiden disagrees with it, at least to an extent. Instead of crafting one single “good” vision of the game that everyone experiences, it builds a framework for offering a multitude of visions. You can tweak the difficulty of the game through different sliders like enemy stats or aggressiveness. The game utilizes a nonlinear structure where you pick which stage to tackle first, while the ones you don’t pick gradually expand in length and difficulty. As you progress through those stages, the game offers a random selection of upgrades for you to pick from in order to give you an edge. Depending on how you tweaked things, at the end you’ll cash in your points for a payout of tokens that can be used to unlock extra content.

Basically, the game offers a lot of gimmicks to keep you playing. That isn’t an inherently bad thing, but it does tell you where this game’s priorities lie. Double Dragon Gaiden does not trust its core gameplay to keep you coming back and instead outsources that task to various subsystems. This emphasis on replayability informs how the game is designed in both positive and negative ways.

Let’s first remove all of that replayability gobbledygook and examine Double Dragon Gaiden as a normal beat-em-up game. All games in this genre rely on basic principles of spacing and timing – you constantly move in and out of your enemy’s range of attack to land your own hits at the ideal time. Double Dragon Gaiden pushes that foundation to a noticeable extreme. Each playable character carries themselves with a noticeable weight; they don’t move particularly fast and their attacks will often have a lengthy “recovery” period after execution, which leaves you unable to move for a second or two. The first word that popped into my head while playing was “slow”!

I don’t actually mind the lethargic feel of the combat that much. The commitment it asks of players when pressing buttons gives the game an engaging learning curve. Once you take some time to adjust, it all feels natural and keeps you thinking about your next move. The slower pace also complements the main mechanics that Double Dragon Gaiden throws into the mix to spice things up.

A tag system and a “crowd control” mechanic put a spring in Double Dragon Gaiden’s weighty steps. Whenever you begin a game, you select a team of two characters that you can actively swap between. This system adds some variety in movesets as well as some strategy by providing some defensive options when you find yourself locked into an enemy’s assault. A sudden swap can allow your partner to swoop in and save your partner, although a poorly timed tag can just as easily result in both your fighters getting beat down. It’s a fun if underutilized idea. When it comes to a system like this, I half-expect it to blow the door wide open for creative combos and options, but the “get out of jail” card element to it ends up being the most compelling argument for its inclusion.

On the other end of the spectrum, the “crowd control” mechanic risks being too prominent for its own good. The idea is sound: the more enemies you group up and defeat with one special attack, the better the game rewards you for it with food powerups. However, this concept takes over how you think about the game in a big way. Crowd Controlling is how you restore health and, more importantly, how you maximize your score. That being the case, I always found myself fishing for crowd controls by waiting for enemies to group up. They’re flashy and feel good to pull off, but both the process of waiting around and the “Crowd Control” notifications that pop up on the screen after doing them slow down an already slow-paced game.

Ultimately, these bigger ideas establish an identity for solid if unambitious combat mechanics. Other little tricks and nuances exist to add some depth, like being able to cancel certain moves with runs or jumping to give your character a brief window of invincibility. No matter your tactics, however, it all comes back to those long periods of vulnerability after attacks. Everything you can learn is either to avoid that drawback or minimize your risk of it putting you into bad situations.

The sluggish recovery speaks to my biggest gripe with the game. It feels like it was balanced to justify all of those aforementioned difficulty sliders rather than what would make the game most fun. So much of the nuance of the combat mechanics revolves around defensive measures when it has the potential to do much more. This is a game where you have near constant access to tag-teams, devastating super attacks and crowds of enemies to unleash them on, yet it pulls those ideas off with noticeable restraint. On one level, the game simply doesn’t give you a lot of options to go on the offensive. On another level, it’s best you don’t try too hard anyway because the game will punish you mercilessly for it.

Double Dragon Gaiden’s framework suits a crowded, chaotic kind of game where people are constantly being pummeled; the problem is that it best suits it when the person being pummeled is you. One wrong move, especially in boss fights will result in the enemies eviscerating your health bar as they all gang up on you. I found that using a character like Marian, who specializes in long range gun attacks and crowd clearing rocket blasts, to be the only relatively safe solution. If you run back and forth while clipping enemies until your super meter recharges, you can keep enemies at bay and yourself out of trouble.

When you crank up the enemy’s stats and aggressiveness, a drawn-out, defensive style of play becomes the default approach. Some fun can still be found here, but overall it makes playthroughs drag. This problem can’t be cleanly avoided with how the game is designed.

No matter how you tune the difficulty, the core concept of the game is that it becomes more difficult as you progress. The fact that the game can reach a point where the core combat mechanics are insufficient for enjoying it justifies the nonlinear structure of the game, the upgrades, and the presence of the difficulty sliders.

When you sacrifice the actual gameplay for subsystems, the end result should be worth the trade-off. The focus on replayability does have merit.

I enjoy the ability to choose your stages the most. As the game opens, four separate gangs take advantage of a power vacuum caused by society’s collapse in the wake of a nuclear war (by the way, Double Dragon takes place in the post-apocalypse in case you missed that). You choose the order you tackle each gang in, with the idea being for each one you defeat, the others grow in power. This makes the enemies tougher and the subsequent stages expand with additional areas.

The expansions in particular add to replayability in a fun way – some stages contain nastier environments than others, and the last stage you pick will always supercharge the boss for an appropriate final encounter. Once you know the differences, you can plan out which stages you want to breeze through and which you can accept at their worst.

Beyond that, most of Double Dragon Gaiden’s replayability options boil down to mostly stats. The difficulty sliders focus almost exclusively on stats. Purchase upgrades ideally should result in new ways to experience your character and create new playstyles, but that’s not how it pans out. Unfortunately best upgrades have less to do with making the game more fun or interesting to play and more about remaining competitive with the enemy’s stats. That’s okay, just not particularly exciting.

All of these subsystems feed back into tokens. The higher you set the difficulty, the less times you need to revive, and the less upgrades you buy, the more points you can convert into tokens. With these tokens, you unlock more playable characters, art, hints, and music. This is theoretically the end-all-be-all reason to continue playing the game. Everything I mentioned above boils down to collecting these things.

Do the tokens make the game? Do all of these replayability ideas extend Double Dragon Gaiden far beyond the lifespan of the average beat-em-up? Why am I asking you these things? Hopefully I’ve asked enough questions here to build up the suspense.

Well, I played through the game in its entirety about five times. Through these playthroughs, I experienced every major variation of the stages. I defeated the strongest versions of all of the bosses. I tried out a dozen characters and bought more than my fair share of upgrades. Most importantly, I earned more than enough tokens to completely buy out everything in the store.

“Oh, that’s it,” I thought as I closed out the store for the last time. I officially exhausted everything that this game was seemingly built for in less than ten hours. Maybe five playthroughs sounds like a lot, but for this kind of game I don’t think it is. I’ve played my favorite beat-em-ups dozens of times, some probably even approaching triple digits. Sadly, I don’t expect that I will be approaching anywhere near that number for Double Dragon Gaiden.

It’s not like Double Dragon Gaiden isn’t a charming game. The cutesy 2D art brims with personality. The soundtrack leans heavily on remixes, but they are energetic ones that revitalize tracks from throughout the entire mainline series. Some of them are so good that they’ll make you say “Double Dragon IV had a soundtrack!?” when you unlock the songs in the store and find out where they’re from.

However, the main selling point of the game holds it back. In its rush to add a lot of things, it fails to execute on the single most important thing: being unequivocally enjoyable to replay on its own merits. Arcade games always walk a tightrope of balance, but that just makes it all the more important for them to be balanced by the steady hand of the development team. If you leave too much room for players to tip the scales however they like, that can prevent the core experience from making an impact.