6. Oca

I may be more enamoured with Oca’s structure than with the film itself. The Mexican film, written and directed by Karla Badillo, is a minor odyssey featuring an ever-increasing cast of spiritually lost characters, each searching for an archbishop in the nearby but seemingly unreachable town of San Vicente. The idea of a disparate ensemble linked only by their shared, single-minded goal is so appealing to me that I find myself able to ignore the film’s obvious shortcomings. The dazzling shots of untouched Mexican vistas don’t hurt, either.

We begin with our main character, Rafaela (Natalia Solián), a nun who’s sent to fetch the archbishop and have him revitalize their all but non-existent congregation. Slowly but surely, we’re introduced to the rest of our archbishop seekers: a handful of bickering residents from a small town who wish to present the archbishop with a statue of their saint; a mysterious, wealthy woman who wants to know if she’s a good person; and a soldier on a contentious political mission. These storylines inevitably intersect, causing quaint chaos as motivations and divine understandings clash.

Rafaela’s story, unfortunately, is the only one that gets enough context to resonate. The other journeys are interesting in what is present, but so much necessary information is inexplicably absent. We get no backstory whatsoever for the wealthy woman and no explicit understanding of the soldier’s commands, rendering both of them only approachable at an arm’s length.

Rafaela is fascinating, though - when we first see her, she’s just received a dream that the head nun treats as a prophetic vision. Along the way to San Vicente, we see Rafaela treat her fellow pilgrimage-goers with a kind but cold distance, and she receives vague hostility in return. She is caring in moments, entirely ambivalent in others. When she reaches the archbishop at long last, Rafaela receives some unwanted wisdom: anyone who claims to be a prophet is arrogant, mad, or very special. Odds are against the latter.

Oca’s complicated relationship with religion comes into focus with a scathing proposition - attempting to interpret the will of God will say nothing of God and everything of the interpreter. God’s plans are not to be understood by us mortals; we’re only along for the ride, so to try to find meaning or pattern or expectation in His decisions is only a reflection of our own selfish desires. To provide my obnoxious atheistic take, Oca rejects scripture provided by mankind, invoking a more unknowable perspective of theology. The film provides such a strong thesis and structure, it’s a shame that Oca is slightly less than the sum of its parts.

5. Babystar

Good afternoon, good evening, and goodnight! Babystar is a cautionary tale, a not-quite-horror coming-of-age Truman Show-referencing satire aiming down sights at parents who feel the need to broadcast their - and their children’s - every waking moment. Set largely in a boxy, modernist German home, Babystar provides its own all-access look into the life of 16-year-old Luca (Maja Bons), the only child of vlogger parents (vloggers first, parents second) Jurek (Liliom Liwald) and Stella (Bea Brocks). When Luca finds out that she may have a new sibling on the way, she’s sent down a spiral of hate, confusion, and self-discovery.

I say Babystar is not quite horror since the film’s tone doesn’t fully come into focus until its final moments. The film is replete with instances where, with a lesser director, Luca would have most certainly committed gruesome acts of violence against her negligent parents. Director/writer Joscha Bongard, however, keeps things teetering on the edge of carnage but consistently rushes back to reality, making for more grounded insights into Luca’s mindset. The result is a more effective satire, one that heightens the obvious real-life observations the film is trying to make but keeps them relatable and occasionally heartbreaking.

Luca’s journey feels somewhat episodic, with her being initially (non-forcibly) confined to her house and comforted only by a creepy AI version of herself. She makes a tentative friend when a producer comes to visit with some young fans, setting up Luca’s eventual search for meaning. Subsequent chapters feature different, often tragically hilarious ways in which Luca tries to find her connection to humanity after being relegated to parasocial relationships for so long, all to no avail.

Despite Luca being social media famous for her approachability, she finds herself helpless when it comes time to interact with real, flesh-and-blood human beings. The film’s biting sense of humour keeps things from feeling dour, and its deliberate, colourful cinematography gives Babystar a glib sense of superficiality. Some steps on Luca’s road to relatability are more effective than others, but the ending finds a way to tie it all together in a bittersweet bow.

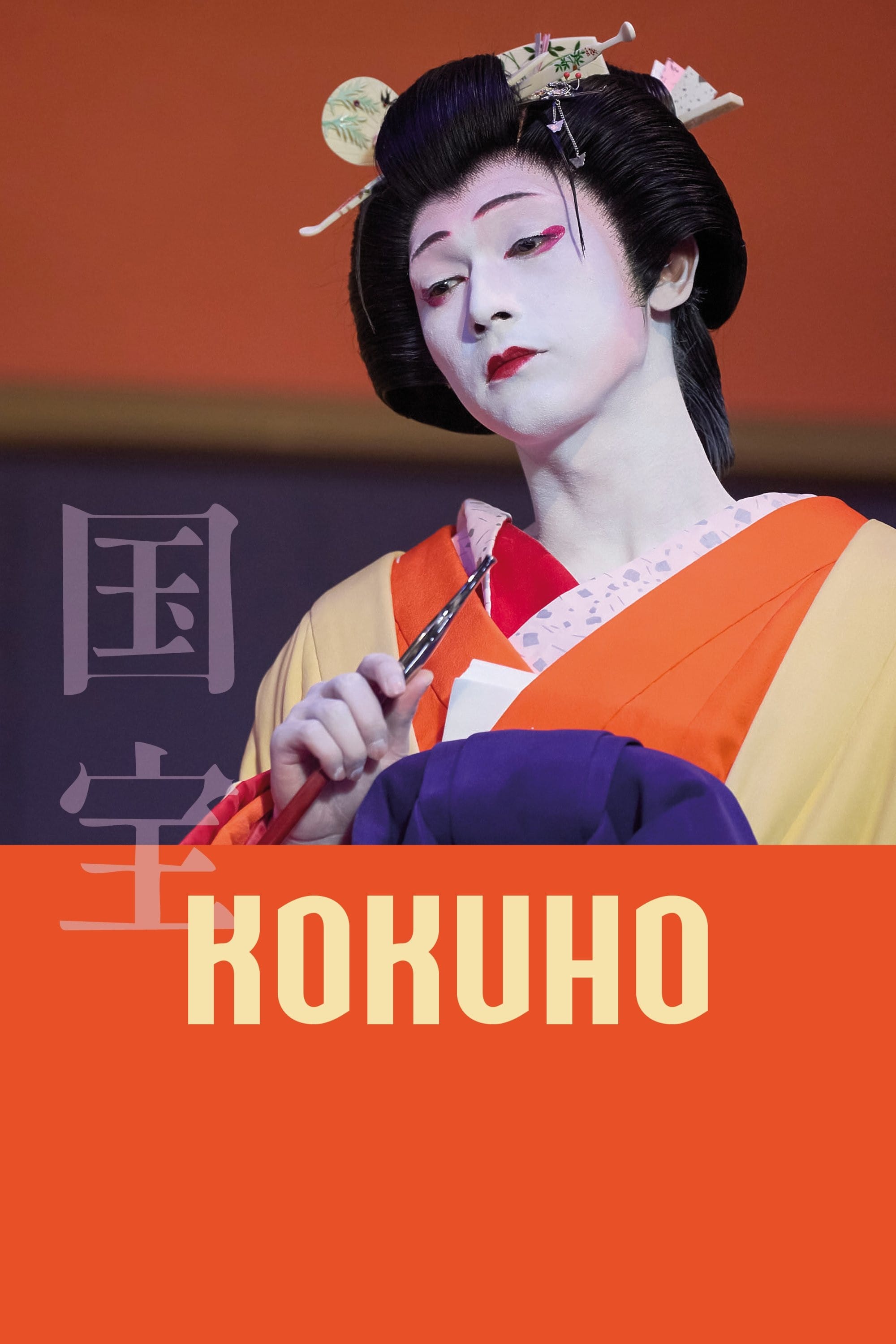

4. Kokuho

Set in the elegant world of Kabuki theatre, Kokuko is an epic built around the volatile friendship between two performers, each striving to be the greatest of all time. I went in knowing next to nothing about Kabuki; I had seen the costumes before, but it was an otherwise entirely new storytelling medium for me. The odd method of speak-singing and the over-the-top makeup came off as silly at first, like a confounding form of opera (which is already rather confounding). By the end, though, I felt intimately connected to the art and the inimitable feelings it can evoke.

The film begins in 1964 Japan, with a relatively amateur Kabuki performance from 15-year-old Kikuo Tachibana (Sōya Kurokawa at this age, then Ryo Yoshizawa once older), the son of a Yakuza boss. The performance turns tragic when a rival clan attacks and kills Kikuo’s father, initially sending the young man on a path of violent revenge. But Kikuo isn’t destined for a life of crime - he’s taken in by Hanai Hanjiro (Ken Watanabe), an aging Kabuki star who sees great potential in him, instilling in Kikuo a crucial piece of advice: the best revenge would be to honour his father and become the greatest Kabuki performer alive. Also gunning for GOAT status is Hanai’s son, Shunsuke (Keitatsu Koshiyama, later Ryusei Yokohama), who forms a fast friendship with his new housemate. We follow the two through five decades, chronicling their complicated bond as they rise through the ranks of theatrical stardom.

Black Swan this is not. While the two will butt heads and be tested by envy and rivalry, their friendship is the film’s heart. The film dabbles in melodrama, mirroring the far more exaggerated delivery of Kabuki, choosing the most emotionally potent moments between the two as points of interest along the decades-spanning timeline. Ambitious but not overly so, Kokuho’s nearly 3-hour runtime is spent exploring every inch of Kikuo and Shunsuke’s relationships with each other and themselves. The two are constantly diverging and then crashing into one another, creating art when they collide and bitterness when apart.

Kokuho is as uninterested in traditional romance as its leads (despite a subplot involving a childhood friend love triangle - no, this isn’t an anime), instead allowing the audience to fill in the words left unsaid between these two men who care deeply for one another. Perhaps those words are too unsaid, though - despite the ripe and obvious stage having been set for at least the hint of a queer story, there’s a case to be made that a gay or trans reading of the film is too subtle to be intentional. Though not a requirement, obviously, there are just enough moments of tangible chemistry to conjure these feelings, without any moments that capitalize on them. And, unless I’ve missed something, I don’t believe there are any deeper metaphors within the “men dressing as women” conceit of Kabuki itself.

Nonetheless, Kokuho is riveting and devastating and undeniably impressive, with its Kabuki sequences containing some of the most resonant moments of the year. Kokuho is already a massive hit in Japan, and I hope it continues to turn heads when it inevitably arrives in Western theatres.

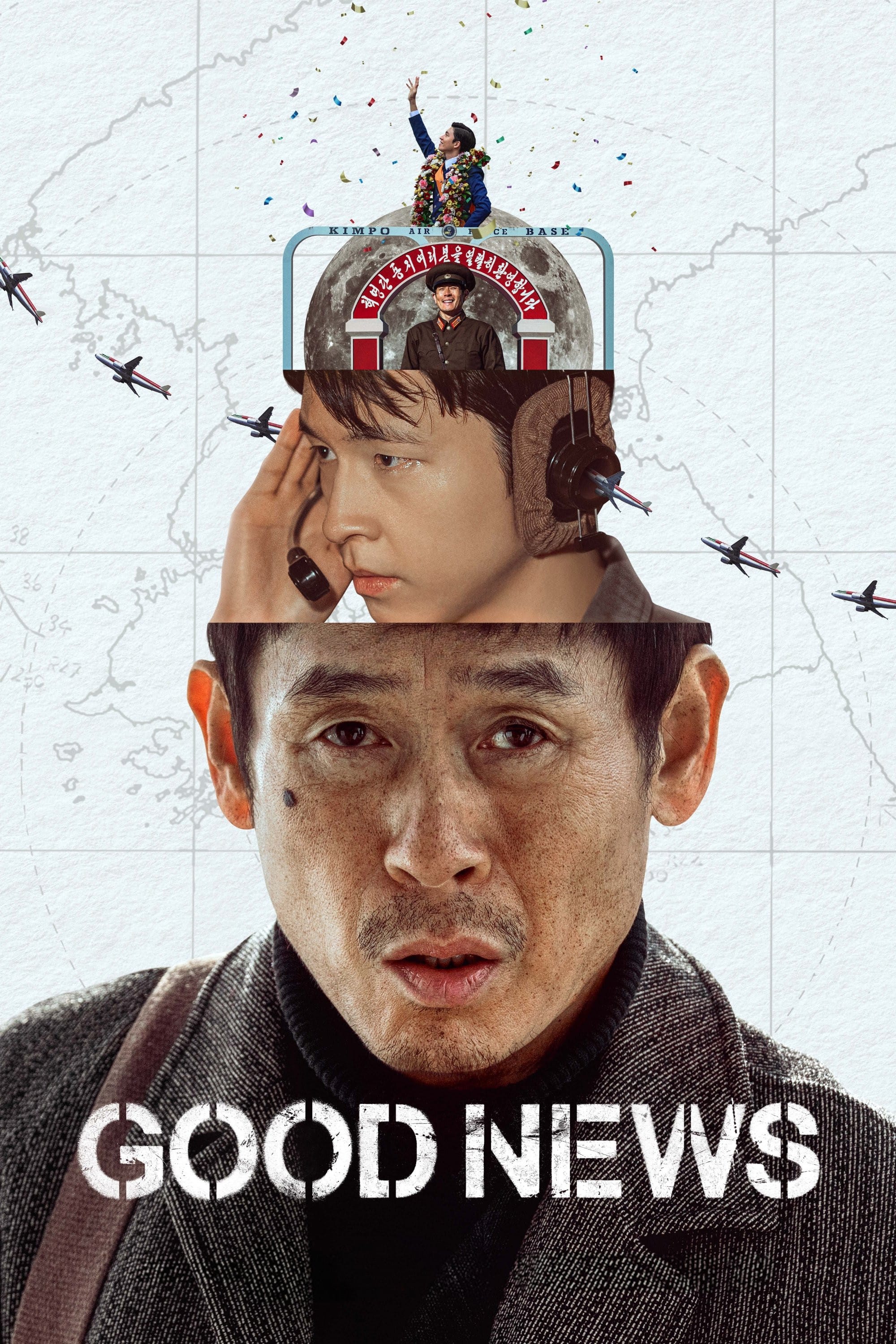

3. Good News

Never has a plane hijacking been so hilarious. Good News, a Korean film from writer/director Byun Sung-Hyun, flips the high anxiety of a political thriller on its head, crafting a wicked satire of perennial bureaucracy and the death of responsibility.

It’s 1970 and communism is the scariest word in every language. Some young members of the Japanese Red Army Faction have taken it upon themselves to ditch the supposed capitalist hellscape of Japan and hijack a passenger jet headed for South Korea. Their new destination? The communist utopia of North Korea. Armed with knives, guns, and bombs, they take control of the aircraft, sending both the Korean and Japanese governments into a frenzy as they do everything they can to ground that plane. What follows is a Korean mission - headed by a mysterious government agent known only as “Nobody” (Sul Kyung-gu), alongside an underqualified but uniquely capable Air Force lieutenant (Hong Kyung) - to save face, with the secondary mission of saving the airborne hostages.

A phenomenal ensemble cast takes us from one ludicrous plan to the next, as everyone scrambles to pass the buck. The film deftly balances genuine tension with Dr. Strangelove-referencing political parody, both of which it executes flawlessly. The film’s middle section features an absurd grand illusion in which South Korean intelligence tries desperately to make Seoul’s airport into a facsimile of Pyongyang’s in a ploy to fool the hijackers, with results that had me both in awe and doubled over with laughter.

Good News never gets stale, but it does outstay its welcome. The final act, while still fun, suffers from a needless repetition of points made better, earlier. The endless bureaucratic stupidity and unwillingness of the higher-ups to take any responsibility is effective enough without an extra 20-odd minutes that could have easily been cut in service of a tighter conclusion. Regardless, this is a fresh, weighty satire that will surely make a splash when it releases soon as a Netflix original.

2. Sound of Falling

Sound of Falling is agonizing. You will feel an all-consuming sense of dread for nearly two and a half hours, regardless of whether you love it or hate it. Director/writer Mascha Schilinski has shaped a film that’s intricate, meticulously detailed, at times confounding, but is guaranteed to make you feel the way Mascha intended.

We wander through the lives of four women, each relegated to a different time period between the early 1900s and the early 2000s but living in the same German farmhouse, each tormented by trauma and abuse - past, present, and future. Oscillating between the discrete periods often without notice, the film creates a texture of suffering rather than a concrete, linear narrative. The frequent temporal shifts feel alienating at first; it’s not easy to keep track of who’s who and when’s when, and the film almost demands a second viewing. But the feelings remain: Sound of Falling is unrelenting in its presentation of sexual abuse, either firsthand or the effects of bearing witness to it, never outwardly depicting any acts, yet constantly confronting the viewer with feelings of lost identity and loneliness.

This is all wrapped in a film that oozes despair, filled with imagery that looks innocuous but feels sickening. There’s almost a haunted house element, as if the very walls of the home - the only consistency among the timelines save for some familial connections - are providing us with these fragments of terrible memory. The film is not empathetic, it is not empowering, it is not hopeful, it is a pure representation of what it’s like to feel as though you’re never going to stop falling. Sound of Falling was not made for everyone, though I find it hard to believe anyone wouldn’t find themselves deeply affected by it.

1. Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie

Nirvanna the Band the Show is the greatest thing that Toronto has ever birthed. Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol created the show as a web series in 2007, then got a full series that aired on Viceland in 2017 for two seasons. NTBTS combines improvisational banter between Matt and Jay (playing fictionalized versions of themselves) with real interactions with the good people of Toronto, all of whom are entirely unaware that they’re actively influencing the narrative of a TV show. Each episode features a different harebrained scheme that will surely result in Matt and Jay achieving the impossible: getting a show at the Rivoli, a local bar/restaurant that has live music on occasion.

The film is no different; of course it begins with another one of their brilliant plans (this time involving a base jump from the CN Tower). The film quickly goes even more off the rails, though, taking the duo back in time to when it all started - Bill Cosby, Jared Fogle, and Jian Ghomeshi (a Canadian creep, for those unaware) leer at them from newspapers and ads while an audience laughs uproariously at Bradley Cooper dropping the f-slur in The Hangover. Yeah, it's 2007. We're treated to one enlightened gag after another, some involving meticulous planning on the crew’s part and some stemming from the unpredictable Toronto public. Matt and Jay's ability to improvise and adapt on the fly is unparalleled; they somehow manage to elicit something hilarious from every inch of this fine city.

The duo has so many inventive ideas; it’s unfathomable how they possess both the humour and the technical expertise to flawlessly pull off anything they think of. An early section of the film involves the reuse of their own footage from 17 years ago to create the illusion of having time-traveled, seamlessly weaving the past and present together in a way that makes it feel like this movie was 20 years in the making. This is innovative comedy, à la Nathan Fielder but with the silliness turned up to 11. Even if you’re not Torontonian, you owe it to yourself to check out the genius of Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol.