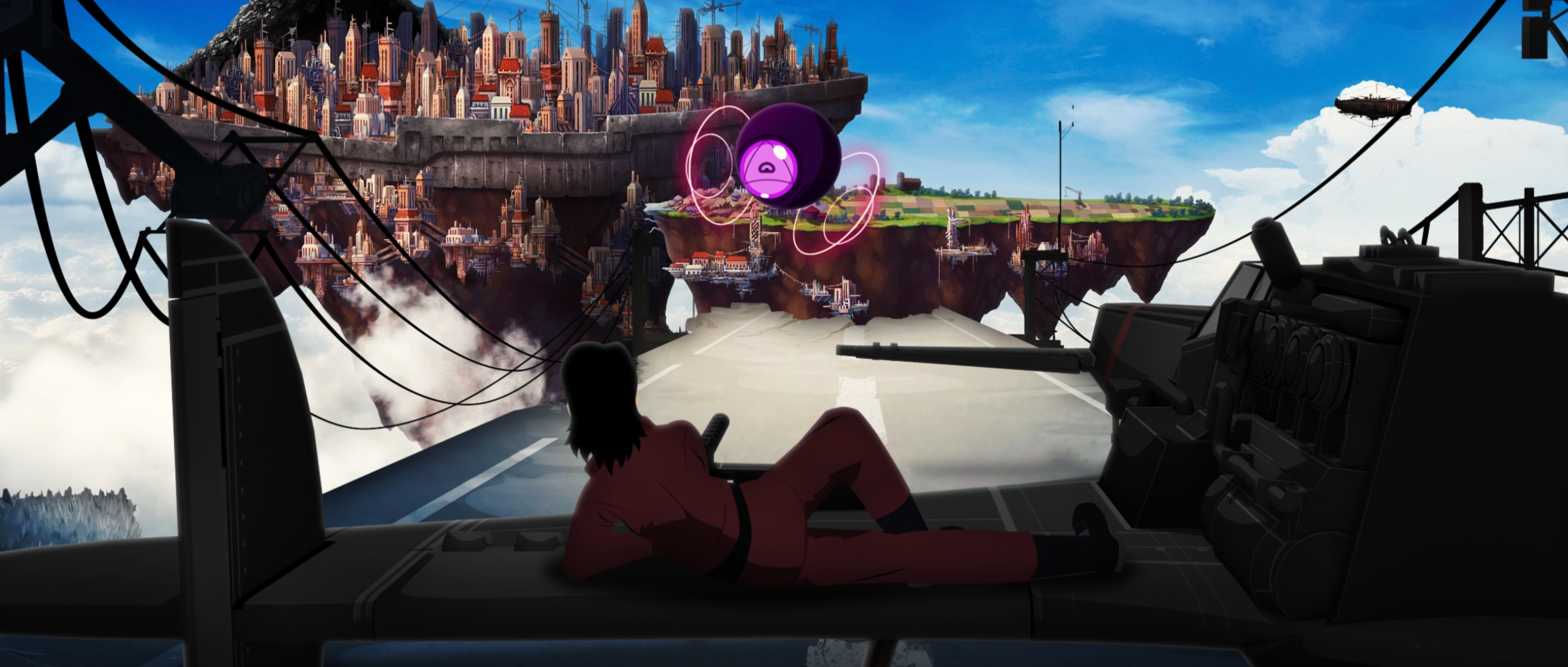

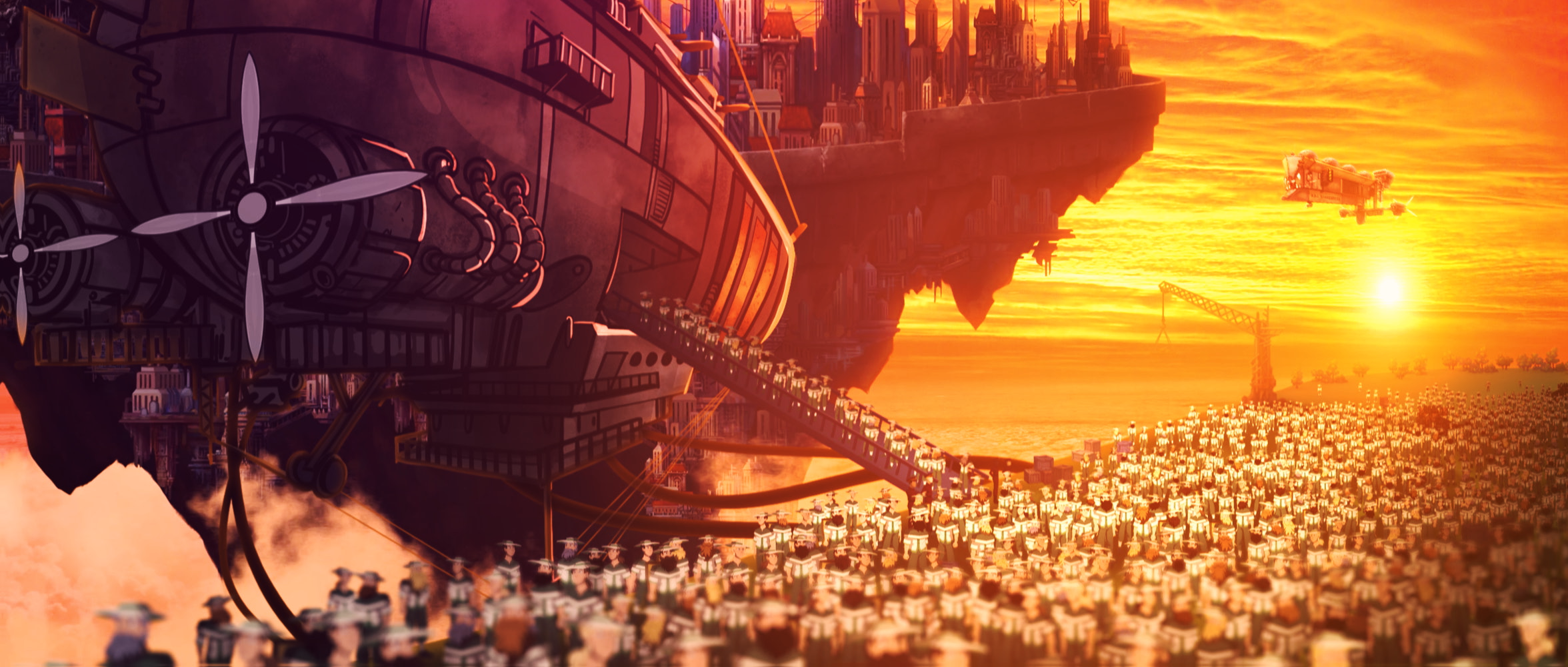

Song in the Sky defies description, but I’ll try my best. An independent horror/action animation, the series takes place in the last Haven of mankind, a city floating in the air above the murk of an endless sea of darkness. Stretching on into the unknown, possibly forever, the Abyss houses inhuman god beings that rise to smite Haven, protected by a fleet of airplanes and a few friendly denizens of the dark below. With its pilot animation released in 2018, a small team has been hard at work bringing the story to life, and today sees that revival, in one of the most stunning, glorious, ambitious works by a small team that I have had the good fortune to witness.

More than description, Song in the Sky defies reality. It shouldn’t be this good. Something this outlandish and work intensive couldn’t, so the modern film industry tells us, be made at all. Yet here it stands, as defiant as the pilots it depicts. Owing influences (direct and indirect) to Evangelion, the Night Land, and Ghibli, Song in the Sky stuns in its grandeur, its intrigue, its quality of design, and the simple impressiveness of the fact that it exists at all. Though it was supplemented by voices, concept/background art, and writing by a small team, the bulk of the conceptualization, directing, animation, and production fell solely on the shoulders of one Samuel Frederich. I spoke with him about his project, his process, and the dedication it takes to bring your vision to life, even if mostly on your own.

Song in the Sky spins a dense web of action and worldbuilding. Haven’s denizens know of their gods through ancient, Biblical verses, with little verification other than their destructive potential. Coming back years later, this held one of the more surprising reveals: that the pilot’s theme song, an atmospheric and haunting melody, was actually one of these verses, hiding lore in its depths for all this time. Its sweeping stakes and character designs bely a deep emotional throughline and careful details hidden all over the frame.

Sam is an animator/writer/editor living in Los Angeles, but originally from nowhere and everywhere. A military family showed him multiple continents and kept him constantly on the move, helping to inform an expansive view of art and stories, and some of the visual design of Song in the Sky’s planes. He got into UCLA but decided on a small school in Minnesota, where he subsequently realized he wanted to get into film after all. This proved a boon, as he was insulated from the cut-throat relationships of Los Angeles that many filmmakers I speak to lament for its degradation of the form. He’s gained an appreciation for weird, outsider art. Flaws and all, any piece where a director with vision takes a big chance has more to say and holds more value to him. Song in the Sky fits comfortably in that mold.

Working large projects on your own is a multifaceted experience. It’s liberating to let loose your own ideas without restraint, but disassociating to work with so little input. As it happens, that was one of the most important learning experiences in this process. His most important note to all independent animators is: “Don’t skimp on the preproduction.” I’ve heard this before, and it bears reiteration. Every minute spent planning saves hours during production and editing. This in large part explains the gap between the pilot and recent release. What was supposed to be one in a line of entries became a larger project because it took on so much additional weight. Likely to be the final segment, it proved that a full series would be unsustainable and its script saw crucial revisions. There was a version ready in 2022, but missing some connective tissue that was so important to the final product I was surprised to learn it wasn’t the main thrust of the story from the start. Thanks are due to Joe Barlak, who worked on the sound design and was, as Sam described him “an honest, clear-headed, and insightful collaborator during rewrites.”

Community is important on a structural and psychic level for art: you need the perspective of other creatives, but also not to lose yourself in the abyss of a years-long effort. That community came together and gave it their all, elevating Song in the Sky at every level. The emotional core of the story is carried by Nika Burnett and Marley Frank’s performances. Both knew how to inject nuance and subtlety into their roles but swing for the fences when it counted. Dan Grove hadn’t voice acted before this project, but with his work as Andy I hope to see that change. Check out his comedy special Broken Remote to hear more of him letting loose. Mack Johnson’s character designs carried a ton of weight with the world-building, melding familiar and alien designs to communicate a lot of information in a few pieces of clothing and silhouettes. Daniel Bruins took free time to design the main character’s fighter jet model; his work there and during the aerial combat scenes can’t be overstated. Hired originally to design some machines, his work led to some of the most action-packed and impactful moments of the project. Composer James Rogers made some unforgettable pieces, helping to hold the project together over a dense array of emotional beats.

It’s hard work keeping at anything for this long. Unless you’re being paid handsomely you can only keep it up if you have real love for the work. That’s both the final product and the moment to moment tasks that it takes to see the project through. Money is important, in fact the success of the pilot and its subsequent Patreon are the only reason the project could continue, but nothing can replace the importance of making art for its own sake. That love of the craft is what makes independent work so compelling, and industry releases so soulless.

What happens next is, sorry for the pun, up in the air. Song in the Sky will makes its rounds in festivals, and Sam is trying to tone down his ambitions. According to all of his collaborators, his success there is limited, with every idea bigger and stranger than the last. Each short film concept comes back with notes that it needs a feature long release to realize its ideas. That’s not to say that Song in the Sky is doomed for sure. If its success grows and the audience comes along, it could see a longer series. YouTube is an unpredictable beast, hence comes this article and my personal request to all of you: watch the show, share it, and spread word of mouth. We can’t rely on the studios to make something this interesting, but we never had to. The artists are out there already, as are the means to support them. Go forth.

That said, the current state of Song in the Sky is anything but a failure. Despite a few hanging questions (that I, abusing my position as small-time press, got answers to), the release is a complete story, and one that will more than satisfy. I can’t recall another time I got so much depth and inspiration out of 40 minutes of film, and I will be happy to see whatever else Sam puts his hand to. The independent revolution is already here, and it’s high time the audience takes note.