I hate Caylus.

I note that this is probably a bad opinion to own. My encounter with the World’s First Worker Placement™ missed a key rule and robbed it of some potency, so in a practical sense I’ve never played it. When a mind like Cole Wehrle’s praises its mechanical clarity, I should be wary of this opinion. Nevertheless, I hate Caylus.

I hate Caylus because unlike most of the people who approach this assemblage of wooden houses and spreadsheets, I expect to see a castle in the end. I don’t need it to be pretty and I’ll happily swap cubes for generic victory points until the cube-shaped cows come home (for 0/1/2/4/6+ points). But Caylus’ architecture is brutal, lacking even a flicker of warmth in its stony halls. The mechanisms never assemble into the faintest silhouette of a castle, much less a lively tableau of a community flourishing in its shadow.

I confess I take seriously a theme others take lightly, but as I grow older and time becomes more monstrous, the more seriously I regard building anything that lasts.

Zhanguo has a similar story and its base materials don’t differ much from those of Caylus, which had the honor of being “cutting-edge tech” in an industry that’s winding down its wild west era. If I were in the business of easy comparisons, Zhanguo‘s cardplay feels a lot like Brass: Lancashire and its point salad tastes like a Feld with a little Knizia drizzle at the end of each round. Yum! But not what you’d call “innovative.” Zhanguo‘s every bit as rigid and formal as Caylus.

But it finds an unexpected harmony in its arrangement of these conventions, its clean and stately composition. What initially seems like a bundle of stock conventions adds up to something persuasive.

Invariably, a newcomer to Zhanguo will ask some variation of “How do you actually make a point in this game?” That’s a question that’s harder to answer than you’d expect from a “point salad” game.

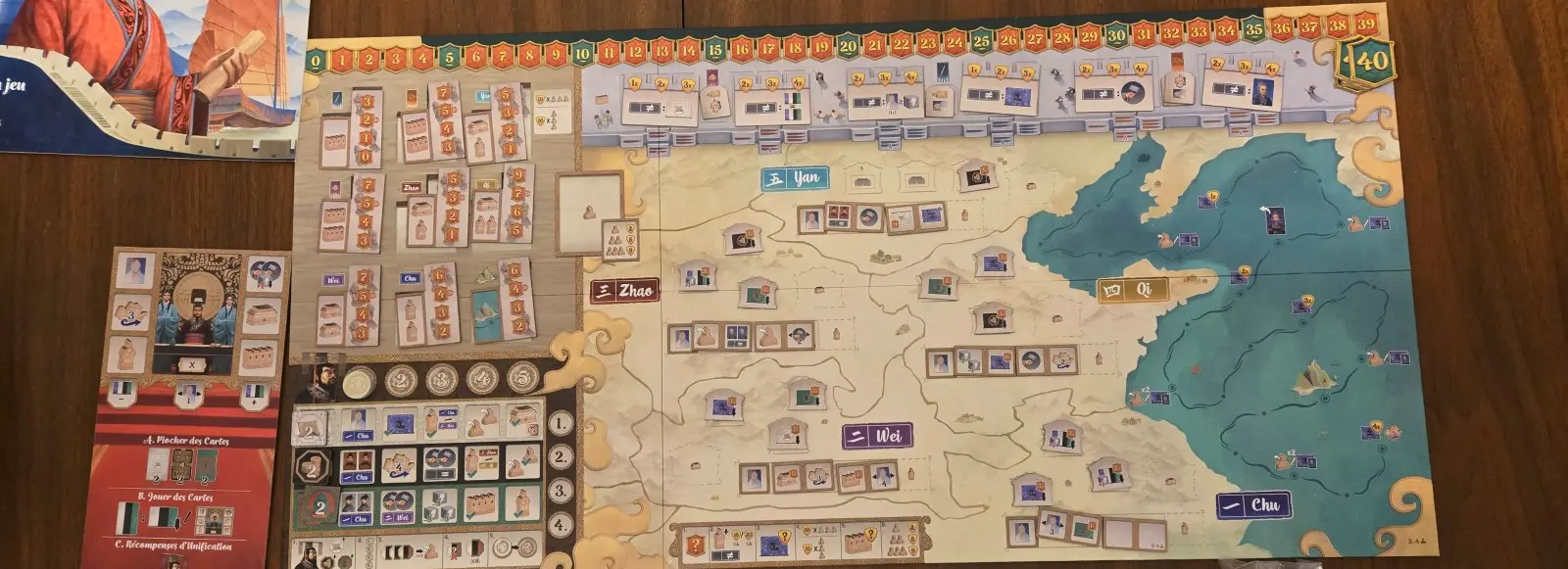

The answer seems to lie in front of them, in the numbers printed next to the tombs and terracotta warriors to the west, the Great Wall to the north, the mystical Yellow Sea to the east, and the fat, unclaimed middle. Between the game’s first print run in 2014 and this tasteful remaster in 2023, the industry has conceived every trick to signpost victory points: every conspicuous font, every corner of a card, and every theory of color. We’ve used laurel wreaths, crests, octagons, wigs, bells, bows, and too many other icons to list. Zhanguo’s second publisher Sorry We Are French—a mouthful for reviewers—knows them well. Its player references and design strike a masterful balance between form and function. Its little orange shields scream, GET ME AND WIN THE GAME.

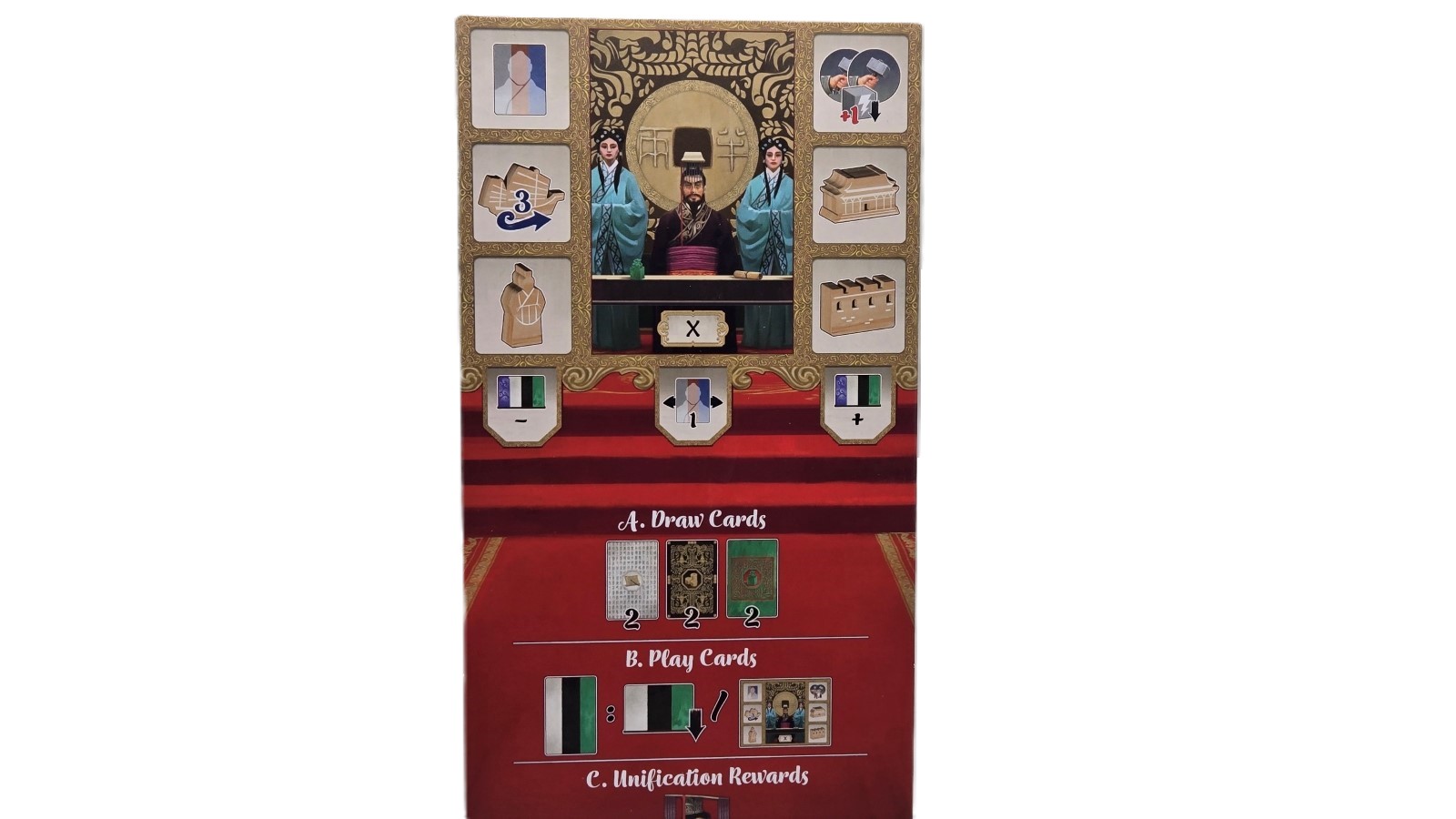

There’s no confusion about the turn-to-turn work either. Play a card to the imperial court (a group discard) for an effect on the empire as a whole or to a province on your private board to (generally) upgrade your imperial actions. True, Zhanguo features more luck of the draw than normal for a complex, long game from 2014. You get six cards per round with no opportunity for a re-deal. But in this decade, Brass: Birmingham does strong business in our local boutiques. Clearly, more than a few enthusiasts of heavy eurogames appreciate the challenge of taming an unruly hand. In fact, this aspect makes Zhanguo look rather prescient.

It’s the scope of Zhanguo’s story that stuns players: the vacuous waste of China’s innards and the intense organization needed to fill it. It needs you to look everywhere at once. It bucks the specialization and vertical optimization of Brass or a Garphill game, which encourage a selective ignorance about the board state.

That’s not a criticism! The ability to filter out distractions and focus on your own routes is a valuable avenue for competitive play and good thinking. It’s just not a good practice in Zhanguo, where Emperor Qin Shi Huang has paired grand expectations with equally grand rewards. The first emperor of China demands that everyone must contribute, that everyone must understand the whole and conform to it, lest they be discarded.

The push for conformity to such a large design is what makes Zhanguo a thematic experience and, in its gamerly fashion, a character study. Within one lifetime, Emperor Shi Huangdi standardized the Chinese language to a degree that would put Merriam-Webster to shame. He minted a single currency for use over 36 territories and 890,000 square miles, enforced by tightly knit network of governors and generals. Something so insignificant as the humble wagon axle was rigorously inspected and measured to fit his new network of roads. [1]

So that sense of being overwhelmed, which strikes you at the start of every game, is apt. The sense of wonder as it pulls together is apt. Unfortunately, you should be feeling some terror, too, and that’s the one dimension of Zhanguo that seems inauthentic. But more on that later.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang had four mandates, broadly speaking, that he placed before his lieutenants, and the four types of card colors reflect them. He wanted a single, uniform language (writing—white). He wanted a bureaucracy with tiers of credentials and exams (jurisprudence—green). As mentioned above, he wanted a regimented network of roads and utilities (commerce—black). He wanted to cheat death (alchemy—purple).

It’s that last part that lends a little blush to the game’s stern visage. Hero or villain, the emperor had a god complex. Much like Alexander the Great, he achieved a level of military conquest and unification inconceivable to his contemporaries. Genealogically, his imperial dynasty ended as quickly as it began: a younger son stepped over the body of his eldest and was predictably murdered by his co-conspirators. The system he (and, by extension, the players) engineered, however, would last until 1911.

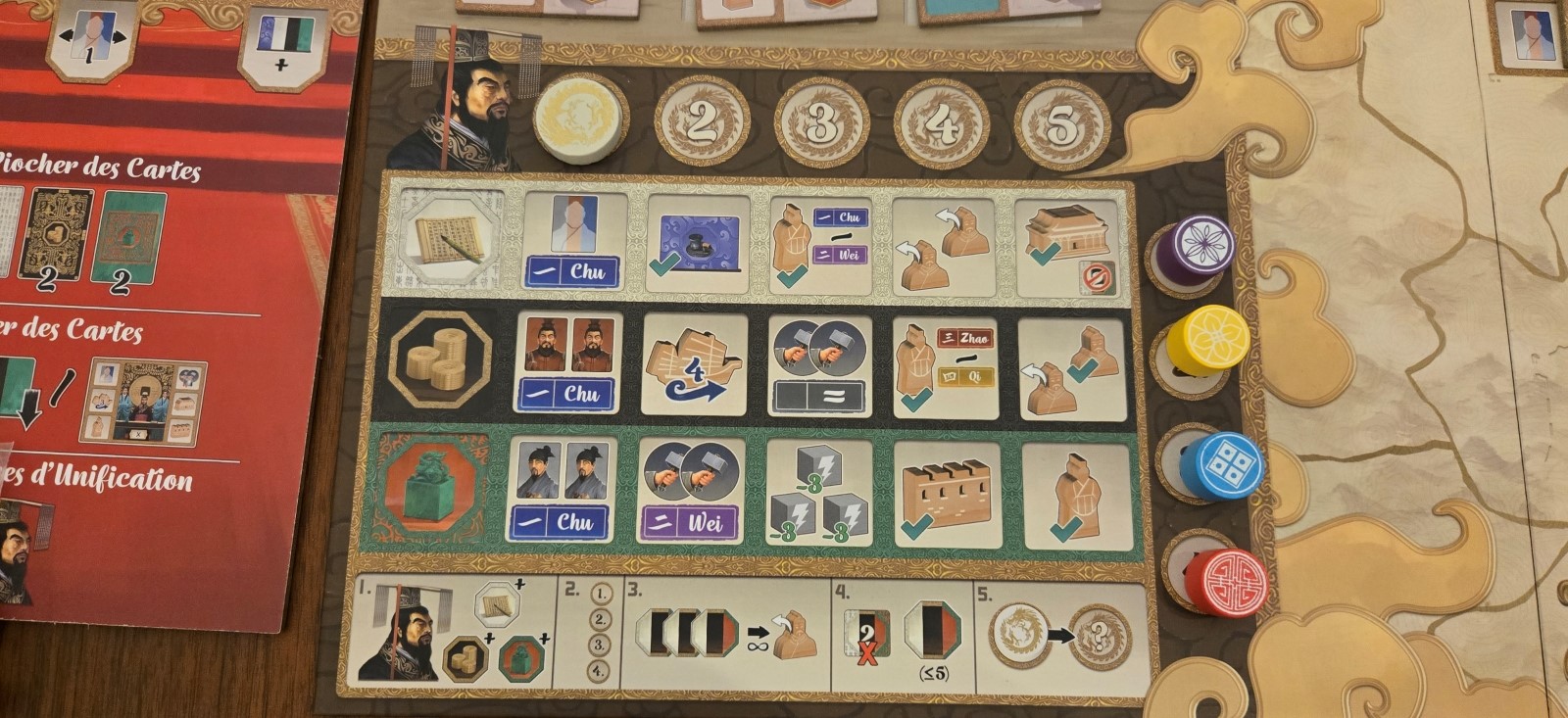

With a resume like that, I suppose you have two options: cry by a river and dream of unconquered worlds or…make an investment portfolio for the next one. Shi Huangdi he hedged two bets and commissioned two teams. Team A (let’s call them “Warhammer”) was a legion of artisans commissioned to build a life-sized, painted clay army next to his tomb to defend his soul. Team B (let’s call them “Brewski”) was a legion of alchemists commissioned to discover the Elixir of Life. The little boat on this track represents your work on the general effort, and the pit stops force you to evaluate whether you want to invest in Team Warhammer or Team Brewski. Make a warrior or talk to your local chemist. [2]

And yes, you count the dividends in points, points, points. Actually placing your warriors in tombs is a Tic-Tac-Toe game barely worth mentioning, though fighting other players to get there will be. It’s a little less bolted-on than Terra Mystica‘s cult track, but not by much. Pursue alchemy and you get some far more interesting cardplay on your province boards, but they’ll just be scored by collecting sets. So far, so Caylus.

But the simple juxtaposition of the two establishes a subtle, poignant tone. Rulers have tried to secure their souls with the prayer of bishops, the strangulation of household servants, by heaping treasures on their coffins, by transferring their sins to cake, and by any number of monuments. What sort of person, as their plan B, martials an army to annex the afterlife? Who would be arrogant enough to try?[3]

The left icon of every card represents one of the six actions you can take at court, one of which moves the ship. The right icon represents a bonus paid out if you take the action to the left. You gain these by slotting it in a province (first picture), along with a chip of the card’s color.

The number in the center? That number ruins your life. It’s a knife in someone’s back.

If you play a card on the emperor and its number is higher than the last one, you can do the stuff on the right. If the number’s lower, you can do the stuff on the left. If none of your cards can give you an action you can afford to do? Well, you might as well have lost a turn…out of thirty turns total. Not much, really.

It’s goofy to think of the emperor at the end of a ticket queue, but it introduces the right level of caprice and a need for flexibility. You can’t cleave too much to either set of actions because what you can do will predictably see-saw…like the serrated knife in your back. Your private boards and priorities are fairly legible. If you’ve gathered a lot of workers, the rest of the table won’t be above coordinating their discards so you can’t put them to work.

Broadly, the left set of actions recruits and employs the nobility. Top to bottom, you can recruit “great people” (architects, generals, or alchemists) to the provinces, sail for immortality as previously described, or combine three great persons in the same province to create a governor. The right side is all about tossing poor workers beneath monuments. The top action musters workers and the other two options sacrifice them for palaces or the Great Wall.

Minus the neat “emperor chits” that modify your cards, Zhanguo‘s palaces and walls amount to the standard tricks in these affairs, implemented competently. Palaces score immediate points and give first-come-first-served bonuses. The Great Walls are endgame targets. These have the same dopamine rush as Terraforming Mars‘ industry awards and milestones, although I find this implementation strictly superior for, if nothing else, modular arrangement those parts. Zhanguo’s constituent pieces interlace and swap as much as something like Lisboa. You won’t suffer for replay.

Then there’s raising the workers to pay for all these wonderful things, and that’s where things get thorny.

I’m not referring to the unrest mechanism tracked by grey cubes above each province. “Unrest” sounds thematic, but it’s really a “cooldown” on card and action abilities which are satisfying to use, but should come with some penalties. Max out the unrest track and you can’t use any of those effects until you build a card engine to cool it down or establish a governor to reset it.

It’s those little grey hammers which deliver a tiny punch to the gut. You can only raise them in a province when it has a general (great person—red). Then when you erect a palace or wall they…disappear. It turns out that Zhanguo has a currency, and it’s human beings. “IMPORTANT: Workers are the only component that is not supposed to be limited,” the rules say. “If you run out of Workers, use a suitable replacement.” Shi Huangdi’s generals drove thousands of indiscriminately collected bodies to the farthest regions of the empire. When they died—from exposure to deserts and frozen wastes, from beatings with bamboo rods, from overwork—they were buried far from home. [4]

Is this too glib a representation for the true horrors lurking beneath? Possibly. The designers of Puerto Rico knew enough about the real Puerto Rico’s foundation to realize that most of its workers would have been slaves. Their wink to the audience, the brown color of the game’s meeples, so outraged those “in the know” that an entirely new theme was created to remedy it.

Emperor Shi Huangdi relocated nobles to his capital under force. He beheaded scholars that didn’t support his legal views. Everything in his golden empire worked because he bent and crushed it into position.

But I think Zhanguo walks on the right side of this line, preserving a fun game night without camouflaging too much. You are clearly gathering workers at swordpoint. You dust them off your board casually. Within the game, you yourself are not entirely your own creature. The emperor provides a separate force to which players must submit. There’s the matter of the cardplay, as mentioned. There are the end-of-round bonuses, which are basically treaties for being such good doggies.

Remember the little tokens you collect when you slot your cards? You refund them for generous gifts from the emperor. The best performer in each category (writing, law, or commerce) gets the choice to turn in their chits for the round’s bonus or refuse. Sometimes you’ll get lucky: the leader will pass on their bonus and the other dogs will have their day. Refusal actually moves you higher in the next round’s turn order, so on a gamey level it’s fun to jockey for position and slobber over big prizes. On a meta level, you’re fighting over table scraps for your master’s amusement. Those aren’t all that different, really.

Does all of this make Zhanguo a rich narrative experience like the ones I discussed with Cole? No. It still runs on points, points, points—a forest of points so thick that a notepad’s predictably included in the box. You won’t dwell overlong on the plight of bricklayers, even if the tapestry on the table feels rich with detail. You’ll be thinking about the next game and how many points Susan just got from her wombo combo purple cards. Ding ding ding ding! Points, points, points ringing loud as a slot machine. The hubris of Emperor Shi Huangdi, in its full terror and glory, remains the topic of another design.

But whatever quality Caylus lacked, whatever kept it off my shelf and out of my life, Zhanguo has. Feel free to strip that down to “immersion” or “dripping theme” (ew!) or whatever you find comfortable. I think those descriptions somehow both overestimate and underestimate the effect. It’s the art of arranging facts grown dry and wild by nature into a shape pleasing to the eye and mind.

Our species enjoys imposing order on chaos, after all. Shi Huangdi understood that, and so does Zhanguo.

[1] Without a college course on the subject, it’s hard to convey the full impact of any one of those efforts. For instance, regions around the Yellow River were in constant conflict due to China’s diverse and interlocked climes. Logging by highlanders sent massive amounts of sediment downstream, turning the water its namesake yellow and flooding the lowland paddies producing millet and rice. Those tuned axles, roads, and arranged specialists made the Zhangguo Canal, originally a plot to drain Shi Huangdi’s resources, the solution to a millennia-spanning problem.

[2] According to the historian Sima Qian, his advisors convinced the emperor that evils spirits barred his search, that they could only obtain the herbs for immortality if he made himself invisible to “evil spirits” (including the unwashed masses). To isolate himself, “he then had elevated walks and walled roads built to connect all the 270 palaces and scenic towers situated within…Xianyang…. Anyone revealing where the emperor was visiting at any particular moment was put to death.”

[3] Or to ingest and surround their body with mercury?

[4] In one of China’s oldest myths, Lady Meng Jiang, a newlywed wife whose husband was collected to toil on the Great Wall, is visited by a terrible premonition of his death. She travels to the Great Wall of the Qi province and learns that he’s already passed away. She can’t find his body to give him a proper burial. She weeps, and her grief is so great that it cracks open the wall and reveals a terrible secret: her husband’s bones embedded in the masonry.