Wizardry: Proving Ground of the Mad Overlord inhabits an odd space in the library of deluxe remasters. On the one hand, it’s a laudable project that makes a worthwhile contribution to discourse around computer RPG design. Designed in 1981, one year after Pac Man and seven before the first Final Fantasy, it invented the core gameplay loop of its genre. The tension and rhythm of party management, of juggling supplies and wounds and fight versus flight, started here. I’d argue that it was perfected here and only a few gems like Darkest Dungeon understood its lessons.

On the other hand and despite many clever quality of life improvements, its demands on a modern audience remain steep. It can’t change further without abandoning its goal to archive a crucial piece of gaming’s past. An appreciation for historical value and some patience will surmount those difficulties and turn this into a rich experience. Without that burning curiosity, it could leave you cold.

In the same vein as Crash Bandicoot’s N. Sane Trilogy or Dead Space, this version of Wizardry has enough fresh assets to skin a brand new game. The enhanced editions of Baldur’s Gate (sorry, Beamdog!), Heroes of Might & Magic III, or Monkey Island seem like a distant memory now. Unlike “colorization” in film (Orson Welles groused, “Keep Ted Turner and his crayons away from my movie”), this liberal application of new technology to old games has been received well critically and commercially. I suspect that it’s because appreciating technology will forever be a part of video games.

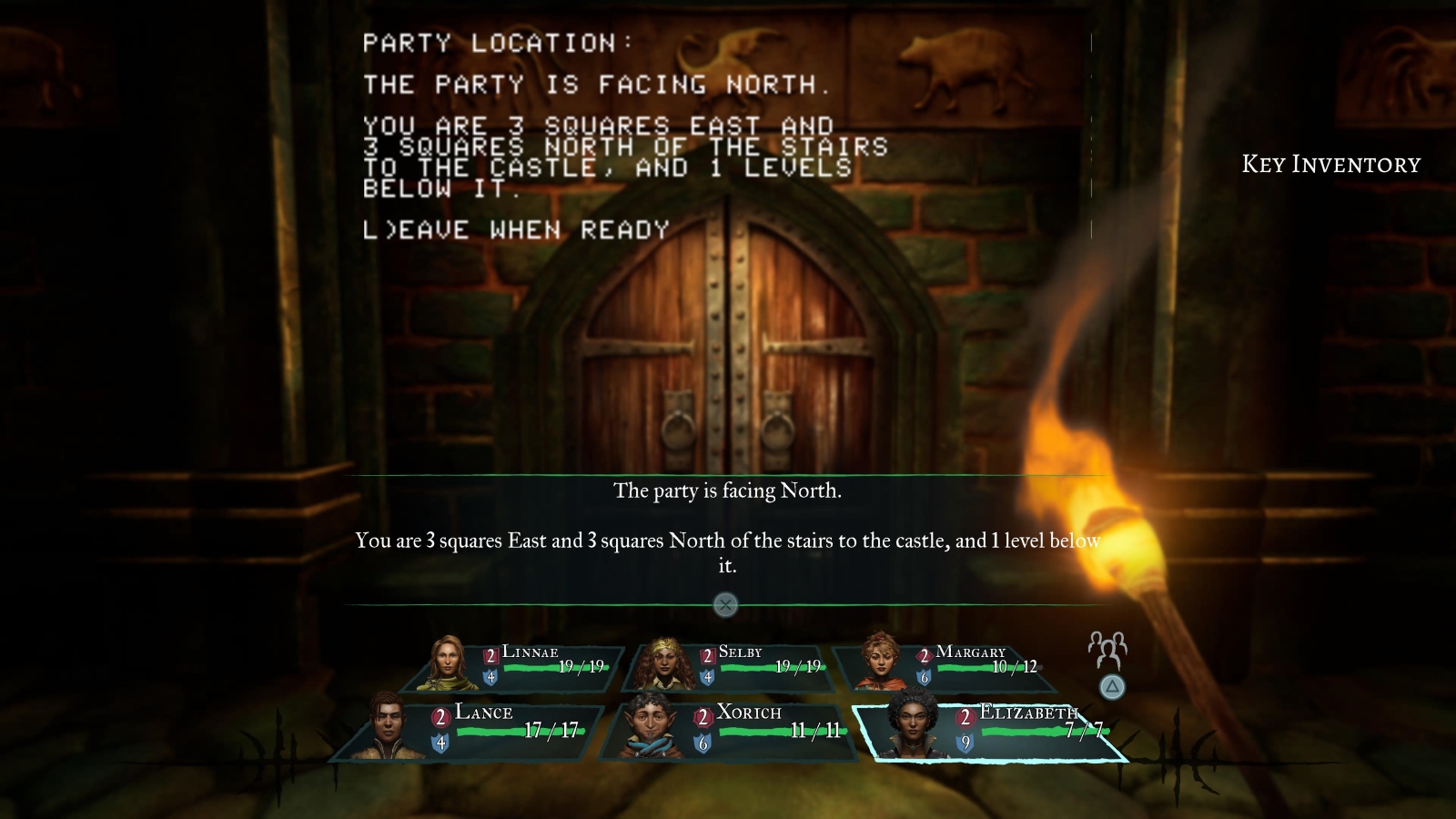

On the PS5, clicking the touchpad lets you view the remaster, the remaster with an embedded pop-up of the original, or the Apple II graphics. I found the contrast endlessly entertaining. From a collection of nouns and Apple II doodles, the developer Digital Eclipse has whipped up some cool art reminiscent of ’80s fantasy. My favorite enemy is a mage that waves his staff around like a kid at Dave & Busters and cries, “Aha!” in his best Ren Faire voice. It’s all so campy and utterly charming. Like most early RPGs, Wizardry wanted to translate 1st or 2nd edition D&D into a computer game, and the style reflects that.

I hit my touchpad. Click. Back to 1981.

The PS5 superimposes the Apple II’s screen over those glossy rock textures and lighting effects. The original mage looks more like a Red Rose Tea figurine covered in dust bunnies.

Your adventuring party, who have an XCom-like disposability to them, become lines of white text. You view the dungeon itself through a porthole, its walls represented by white squares and its doors represented by slightly smaller white squares inside those white squares. Bear statues, ghosts caged in crystals, and elevators will feature prominently in your journey through the proving grounds, but the Apple II conveys them to you through a paragraph of text inside, you guessed it, a white square. That text will flash once and you need to use the oft-useless “inspect” action to interact with it, so I hope you wrote down the x and y coordinates on your map.

You heard me. Write it down on physical graph paper with a physical pencil.

Some veteran PC gamers claim this hardship as a badge of honor. “You young’uns have gone soft, you and your mini-maps and your macros!” they cry, shaking their Pentium IIIs at the sky. Sure. To school, barefoot and in the snow. Got it.

But the arduous nature of that process underscores the true antagonist of Wizardry. It’s not Werdna, the generic Big Bad who took the MacGuffin for the game’s meaningless plot. Your opponent’s the maze. These floor plans, these warrens, are devious: secret doors; teleportation traps; passageways that double back and wrap around each other. Casting a spell called “Dumapic” will give you (x,y) coordinates, but it might not agree with your map or you might be out of magic.

In those moments, Wizardry becomes quite immersive and evokes a primordial fear. You’re in the woods. The sun is going down. The most familiar shapes and landmarks become strange.

If you have the temerity to retreat from a combat (you coward!), you’ll run a random number of spaces in a random direction. That might throw you into a teleporter or deep into uncharted territory, discombobulating you. It attaches a real price to fleeing, one that’s missing from a lot of Wizardry’s successors.

Smarter breeds of RPG address this in some novel ways. Legends of Grimrock complicates flight by keeping combats in the first-person environment, making maneuvering and entrapment a hazard. Darkest Dungeon has a sanity system that taxes your warriors if you leave the dungeon. The Dragon Quest, Pokemon, and Final Fantasy franchises, however, don’t interact with that mechanism meaningfully. “Flee” becomes more of a shrug. Fight if you want to, I guess.

The combat, spells, levels, character classes, the stuff we associate with roleplaying games—those are distractions. Minus alignment or the rare rule, such as the bishop’s ability to identify magical objects, anyone who’s played any RPG will know what they’re doing. The first Wizardry included an auto-combat feature called “Quick,” which tells you how little time they wanted you to expend on it. My gameplay video above features one of the few combats which requires some thought. Most don’t, and RNG takes the wheel more often than not.

Digital Eclipse has done work in this area to make combat unobtrusive, removing the more Dungeons & Dragons flavors like your choice of rooms at the inn. That’s the smart move. Let RNG have its way. The important part is a sense of attrition.

Here, your party amounts to what tabletop games call a “push your luck” mechanism. Two temptations press you forward: the gambler’s fallacy and the sunk cost fallacy. The former shouts, “You’re on a roll!” and the latter whispers, “You’ve come this far, so keep going.” The smartest people in the world fall for this. No matter how much you remind yourself to stop and resupply, to consider how quickly a few bad digital rolls can doom your fatigued party, you’ll misjudge your risk. You’re so close to figuring it out!

Game over. Back to the village, where you’ll hire new recruits to locate and scavenge the corpses of your older, better funded party. On the Apple II, this means starting a new group from level one.

(Digital Eclipse added a hiring system that keeps track of your best heroes and lets you purchase higher level companions. No starting over from level one.)

The primitive nature of pushing your luck and stripped-down party management lend Wizardry clarity. The title’s Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord, not Tyranny of the Mad Overlord or Defeat the Mad Overlord or somesuch.

Click. Back to 2024 again.

No spoilers!

Of course, no game would dare force that homework on a customer in this age. A gamer in 1981 had a handful of alternatives and they were presumably a child privileged with cutting-edge tech. They approached those demands with enough curiosity and commitment to soldier through. If anyone wants to relive that, you can disable Digital Eclipse’s updates in the menu.

I doubt that even Wizardry diehards will forego them. “A man cannot step into the same river twice because it is not the same river and he is not the same man.”

A mini-map in the bottom left unveils the fog of war as you travel, but it resets whenever you load the game or exit the maze. It can lie to you. When twisted by an illusion or trick, the mini-map will “eat” itself. It represents your characters’ immediate perceptions, not an omniscient point of view. A tile that rotates you 180 degrees will cause you to start walking backward, and the mini-map won’t correct you. That’s a nifty compromise.

Naturally, the spell “Dumapic” sorts this out unless your caster has died (common) or run out of spell points (more common). But now it gives you more than coordinates. Dumapic will project the whole map, complete with a “You Are Here” arrow. You can even bring up the results from your last Dumapic sonar sweep. Behold, technology! Or is it magic? Same dif.

That diminishes the intent, the human error and uncertainty inherent to a map you draw with your own hand. Sure, you use some of the same muscles. The aforementioned “You Are Here” arrow disappears if you refer to the last Dumapic, so you have to match your perceptions, the mini-map, to the features of the last sweep. Doesn’t quite amount to “charting the unknown,” does it? Sounds more like asking for directions.

Look, I realize that I’m lamenting the removal of amateur cartography, and I’m certainly not surrendering the conveniences Digital Eclipse has provided. Well…I struggle to view them as conveniences. That suggests they’re sparing me from some unpleasant, meaningless toil.

From afar, I can imagine Wizardry in its initial form; every floor a riddle, every secret door a revelation. I can imagine poring over my map for an inch I missed. The weather’s poor. Raindrops patter on the window. The paper’s thick with pencil lines, eraser marks, and notes written in the margins. Maybe there’s a secret door here or a key there. I plan to test my theories on the family’s computer tomorrow. Anticipation builds.

Does that sound unpleasant to you?

Not conveniences, then. Call them concessions—concessions to who I am today and who we were then. I can reach the end of this gentler maze and foster an appreciation for the more ambitious, intellectual one.

Resident Evil 4 and Crash Team Racing need little introduction before they’re handed to the next generation. Strip away the chassis, the graphical limitations of their era, and the engine’s rather up-to-date. Wizardry doesn’t do that, can’t do that.

It can provide heritage, something equally valuable. Getting yet another good game from the industry isn’t the only incentive to play or investigate remasters. Longer memories and inspiration flow from them, too. There’s a euphoric snap! when you recognize greatness where you once saw nothing. Wizardry came from nothing or almost nothing, possessing no formal logic about constructing RPGs. The sturdiness of its surviving principles and its internal consistency will forever set it apart. That’s a form of timelessness, too.

Modern designers grapple with meeting expectations, not setting them. Maybe playing this could persuade them to rehabilitate some “obsolete” ideas. Maybe the next hot ticket cRPG will send me to my study and I’ll pore over maps, the rain pattering on my window.