There has been much turmoil in the land of Middle Earth. Rather, its IP holders. Now comes Free League, the chosen one, to right the wrongs of the past. As much as I liked Cubicle 7’s Adventures in Middle Earth, now is a fertile time to look outside of the sphere for The One Ring, second edition. Far from the former 5e adaptation, this reimagining of the game takes all of Free League’s attention to quality and tailors its design toward the exploration, mystery, and corruption that make the Lord of the Rings a captivating story. I don’t have the requisite experience with The One Ring’s first edition to offer a comparison, but the current version easily stands on its own as a way to journey into the wilds of Middle Earth. Twenty-four years following the fall of Sauron, shadows begin to loom in the borderlands. What began as legends and rumors threatens to reach forth and shatter the young alliance of races, and those brave enough to make the journey are tasked with venturing out into the unknown lands and finding what lurks therein.

In a pdf of 248 pages, the core book looks absolutely lovely. Mixed in with storybook drawings and gloomy landscapes are sidebars of elven calligraphy. That’s not to mention the regional maps on offer, separated between those intended for the players and the Loremaster. (Seriously, if you think you may ever play this game, don’t look at the LM’s version.) Not only are the maps an incredible resource for running hex-crawls, their sidebar summaries of the travel system will make the game’s exploration system a breeze to run. The index is a little sparse, but with a sensible enough layout to make that a minor issue. More consistent is the book’s tendency to reference and emphasize a rule, like corruption or exhaustion, long before the point that it actually explains that rule. It’s a shame, because the rules themselves are simple to learn and explain. A reference could get you up and running with all of the game’s nuances in four pages or so, but the actual mechanics feel spread out over more words than necessary. The summaries the game does provide are faster and more useful in some cases than the prose text meant to explain them.

That said, the mechanics are well tailored to their purpose, covering combat, exploration, and social interaction. The basic resolution system has you rolling a number of d6s equal to your relevant attribute, as well as a d12 known as the Feat die. Each task has a target number, and you add the dice together to compare against that target. Any 6s rolled can be used to trigger special effects, depending on context, and the Feat die can lead to critical failures or successes at its bottom or top value. In keeping with Free League’s past games, there is a marginal amount of proprietary dice at play. To differentiate the top value of the d6s and the special Feat die values, they utilize fictional symbols from LOTR which are not the most readable or pronounceable, but are ultimately not necessary if you don’t want to make the extra expenditure. If you have advantage or disadvantage on a given roll, it is represented by rolling additional feat dice and taking the better or worse result. You can use Hope points to grant yourself an extra die or, if you have a magical item, gain an automatic success at the drawback of creating an unmistakable magical effect.

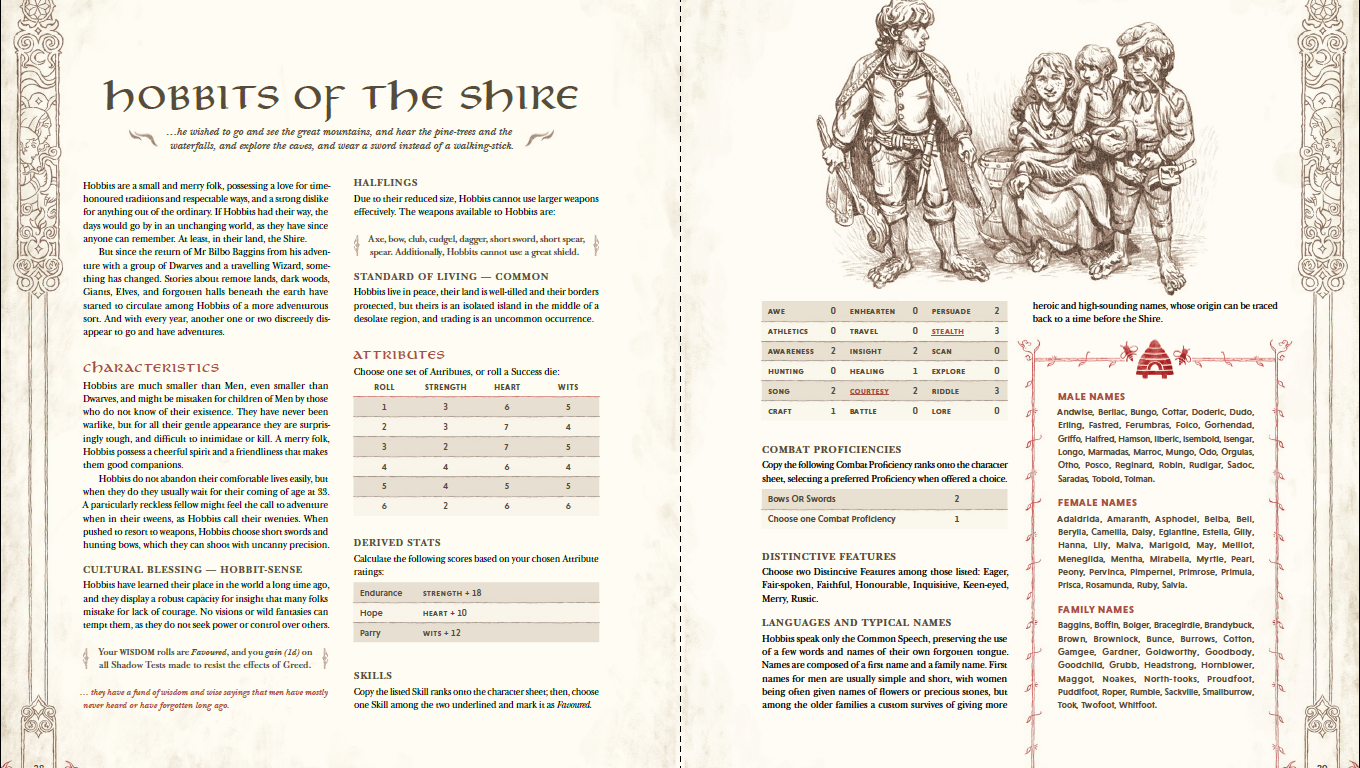

Character generation goes by briskly. You first choose your culture from among a few types of humans and the other races of Middle Earth, which grant a cultural blessing, attribute range, skill options, combat proficiencies, and starting Strength, Heart, and Wits. These three scores are going to be your standard Target Numbers for most tasks in the game. You follow up by choosing your calling, essentially a class, which grants you favored skills (always advantaged, essentially) as well as some very generic descriptors for distinctive features and Shadow Path, the negative personality traits that will get triggered if your character is corrupted by evil. From there you will choose gear from a limited but functional list and starting Virtue.

Similar to feats, Virtues are minor but significant boosts to your character’s stats or abilities. As your character progresses you will improve your abilities, gain more and better equipment, and improve both your Wisdom and Valour while spending experience points. Wisdom represents a character’s inherent capacity to improve and learn from experience, while Valour represents your courage and ability to inspire others. Once your group makes characters, they will also mutually decide upon a Patron, a powerful figure who will commission them for expeditions and offer assistance.

From there, you are ready to set forth on journeys into the unknown. Tracking exhaustion and corruption, you will choose how fast to travel and over what terrain, something that gets more difficult with seasonal weather. The longer any journey is, the more stress your characters will accumulate, making for a game of genuine exploration with risk/reward at its heart. You will have to manage both physical and mental exhaustion, resources that are taxed in different ways. The real heart of the game is in weighing them against whatever your in game goal is. The best way to play this is to pick a direction and start moving, letting the mechanics and discoveries tell your story. For a new LM this is a huge boon. You won’t have to prepare essentially anything, as the narrative is dictated by the map and the players’ course through it. Much like the combat system, exploration is gamified in a way that takes a step back from the narrative in its implementation. For instance, encumbrance is an important rule, but only for certain types of items. Those items don’t have costs in currency, needing to be found or gifted rather than purchased.

The One Ring’s combat system is postured, regimented, and gamified. It’s a great set of mechanics, but one that doesn’t offer total freedom over the encounter. That isn’t a good or bad thing, but it comes down to preference whether you want something more freeform or prefer the tactics on hand. Each round your characters will choose their Stance, which grants a bonus and penalty based on what you are trying to accomplish. Characters attack against their Strength target number, modified by the opponent’s derived Parry score. Successful attacks reduce endurance equivalent to their damage rating, but players can choose to take half damage by allowing themselves to be knocked back. Doing so means you are not achieving your given goal, and are forced to spend the next round recovering your position. You can spend successes to gain extra effects, and have the option of demoralizing enemies or encouraging allies, giving socially focused characters utility in a fight.

Similarly, the Council system allows for social combat of a sort. When in a formal meeting, it forces you to carefully choose your goals and approaches, while allowing for all characters to take part. Much ink has been spilled about whether RPGs need social systems at all, but the Council phase is mechanically engaging and allows for meaningful decision making. Lastly, the game has a Fellowship phase to cover long term passage of time, allowing your characters to achieve larger goals or research ancient mysteries.

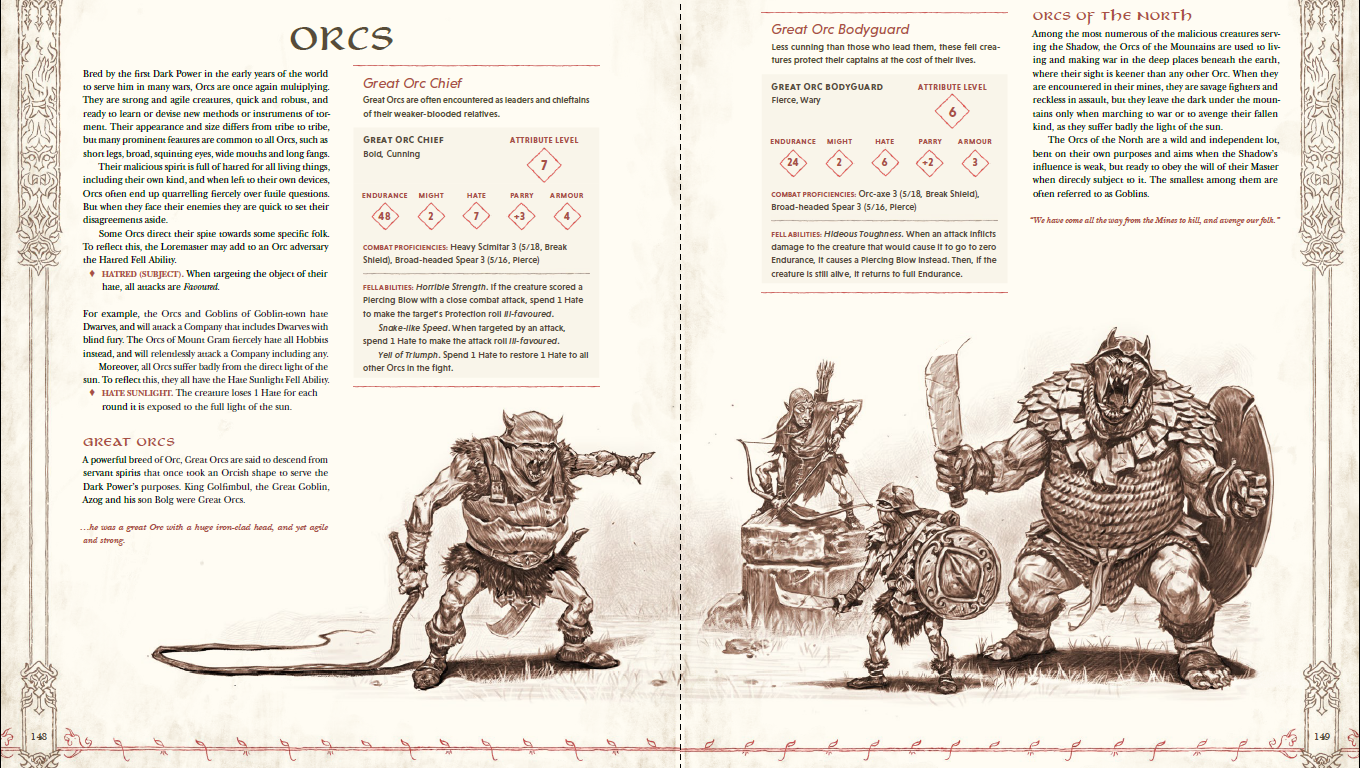

Taking up a solid portion of the book, the Loremaster section has a lot to offer. It covers a variety of topics on structuring games, and takes the rare step of discussing the math behind adversary stats. There are about 20 enemy stat blocks, a functional if not generous number, that should still carry you through a number of adventures. Those stat blocks are concise and usable, not bothering to get into unnecessary areas of detail. Beyond that, the section covers rules for corruption, survival, and the fell consequences of attracting the eye of Mordor. There are also plentiful resources for the general setting, patrons, items, and landmarks.

There are a few notable absences that shouldn’t have a huge impact on your enjoyment of this game. Equipment and character abilities aren’t the most diverse, and this is definitely not a game about making a character build. You will certainly have enough to get up and running for a few games, but may want to look into the (already available) supplements to increase character and adversary options. One odd note about magical items: they are not allowed to be given to another character or permanently removed from a character under any conditions. Meant to signify how powerful and rare these abilities are, it’s another way the game mechanically enforces an idea without necessarily actually representing it in game.