Few things in life hurt more than losing a loved one. It’s a tough subject, so I admire Tales of Kenzera: Zau for choosing to essentially be all about it. Video games sit in a unique position where they can convey empathy and emotion by directly placing you in the shoes of the character you control. Given the subject matter, then, I was expecting Tales of Kenzera to be a tough yet ultimately rewarding experience about parting with someone dear to you. Instead, I found my time with it to be shockingly painless. While I think this game’s heart is in the right place, I ended up wondering if it dulled its edges too much. Perhaps parting shouldn’t be so painless, lest it fails to leave a lasting impact.

I emphasize the narrative here because the game adopts a similar attitude. The game opens with the kind of cut-scenes and forced slow walking segments you’d typically find in big budget, narrative-driven “AAA” games these days. Tales of Kenzera: ZAU primarily follows the exploits of a shaman named, well, Zau. Fair enough. Although his father recently passed away, Zau plans to bring him back by winning a favor from the god of death. This task sends him all across an expansive map, fighting enemies, collecting upgrades, and solving problems. After these opening parts wrap up, it admittedly releases you from its heavy-handed narrative clutches and allows the actual game part to breathe. However, the overlying sense of “narrative first” continues to linger throughout its design.

The opening section gives way to what “we” in the “biz” call a “Metroidvania”. Or at least that’s what the developers and marketing claim Tales of Kenzera is. “Metroidvania” often gets derided as a catch-all descriptor because it implies that any game with the label contains traits specific to both Metroid and a specific subset of Castlevania games. In truth, the vast majority of alleged “Metroidvanias” really only have roots in the “Metroid” part of the equation, so you can call these games just about anything as long as you mention Metroid, from “Metroiders” to “Metroid-em-ups.” I’m thinking “Metroidios” this week. This whole rant may come across as semantics, but semantics matter here because as I played Tales of Kenzera, even the Metroid connection felt tenuous in the face of the game’s true priorities.

Tales of Kenzera earns the moniker of “Metroidio” more by technicality than by a genuine adoption of Metroid’s design sense. Exploration defines Metroid games – they’re all about navigating through maze-like environments to find the way forward. In contrast, Tales of Kenzera’s map reveals its true nature. First, the game sends you all the way to the right side of it. After that, it sends you backwards all the way to the left. Then, it turns you around again for a few screens before shooting you all of the way up to the top.

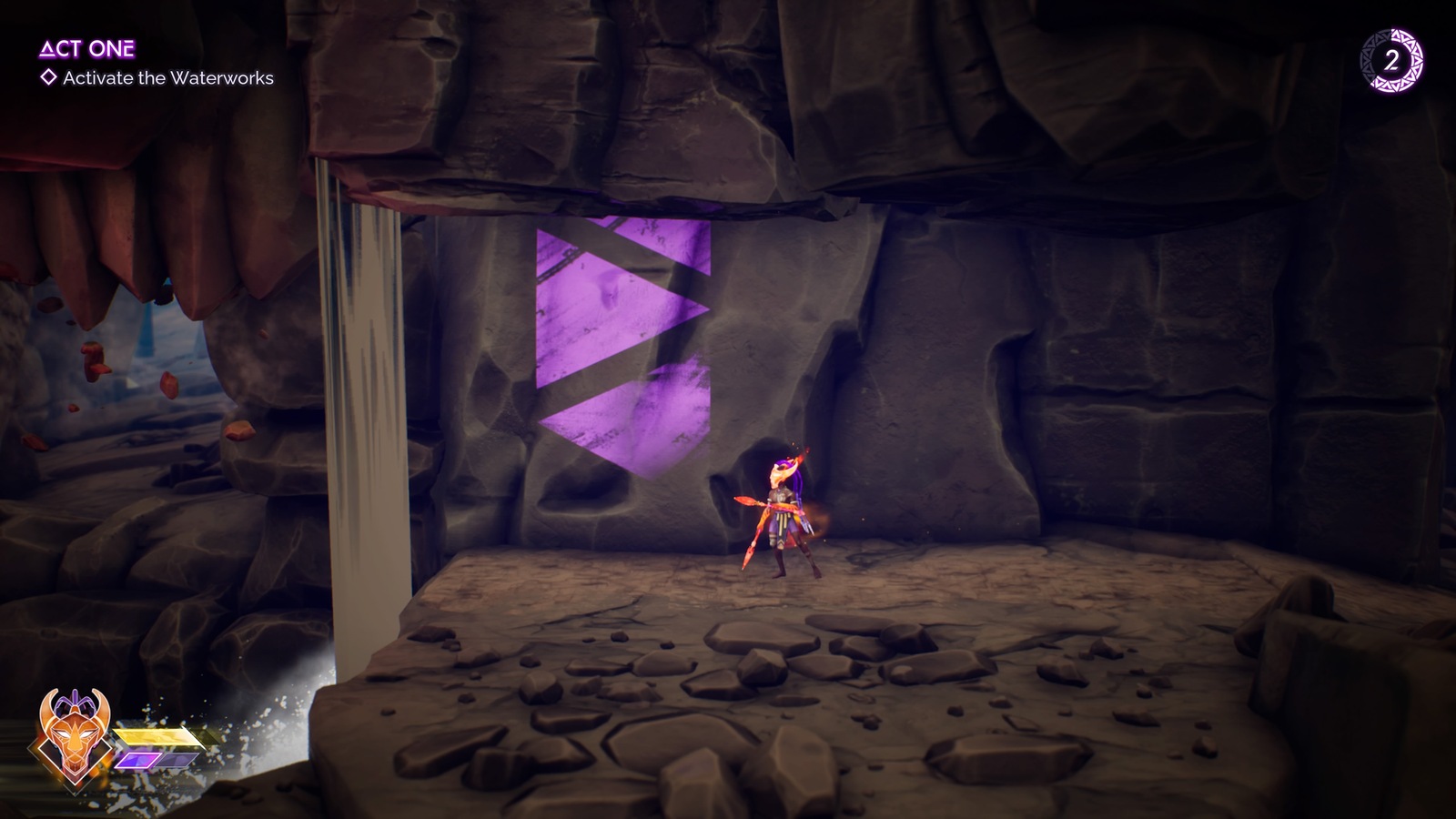

Basically, the game consists of a bunch of straight lines that overlap in minor ways. Yeah, there are some side paths containing some minor upgrades, but they don’t branch far and don’t take up much of your playtime. That’s just the start of how uninterested Tales of Kenzera is in making you explore. Purple paint splattered throughout the environment will signal paths forward, including supposedly secret ones. The map doesn’t interconnect in any meaningful way. As the story progresses, it outright labels where you’re supposed to go on the map to prevent even the possibility of getting lost.

Despite the presence of many Metroid staples like a big map and upgrades to collect, then, Tales of Kenzera ends up being more of a straightforward action game with an emphasis on platforming and combat. The general game structure flips between those two components. You’ll spend the majority of your time traversing environmental obstacles with well-timed hops or using powers like ice blasts to freeze waterfalls, creating a path forward. Occasionally on your path forward, you’ll find yourself suddenly locked into a room with enemies and have to fight them off before progressing.

To Tales of Kenzera’s credit, it all feels great to perform. Zau moves quickly and precisely; he’s well-suited to overcoming the onslaught of platforming ahead of him. With the power of masks he can wear, Zau can switch between combat styles on the fly. The Sun mask allows him to perform close-range melee attacks, while the Moon Mask gives him access to ranged energy blasts. Each mask fits specific situations: the Moon Mask works best for enemies that fly just out of reach, while the Sun Mask can incapacitate ground-based enemies with juggle combos.

The solid foundation of its core mechanics combined with the simplicity of the map design gives Tales of Kenzera a sense of flow that consistently carries you forward. While playing, I rarely felt a hard stopping point or that I needed to take a break from the game. The next milestone of progress always seemed just within reach, providing incentive to keep playing for “just a few more minutes”.

Tales of Kenzera owes its breezy flow largely to its low level of difficulty. Some platforming sections involve insta-kill spikes and some nastier enemies appear near the end of the game, yet these obstacles act more like extremely minor setbacks rather than genuine challenges to overcome. If Zau dies, he’ll almost always respawn just a second or two away from where he met his demise. During combat, Zau can access several “outs” for tougher encounters in the form of a meter that he can use to either heal himself or use super attacks that easily clear enemies off the screen.

To further ease any potential pain, Zau can utilize upgrades. A skill tree buffs the abilities of his masks, his health and super meter can expand, and he can even equip various trinkets that further provide buffs like lowering damage from enemies or increasing the damage you deal. A level of power creep comes with the territory in Metroidios, but in this case the vast majority of what you get begins to feel like overkill.

Between the simplicity of traversal, the low base difficulty, and abundant options to further tone things down, the intent is clear: the people behind Tales of Kenzera want as many people as possible to enjoy the narrative of the game and they’ll do so at the expense of its actual game design. To an extent accessibility can be admirable, and with a publisher like EA I’m sure it’s unavoidable. We’re in an era where the gaming market values getting as many people to play as possible above all else, so I understand why narrative would be the priority here.

However, a dark side to this design philosophy exists that I find hard to ignore. Despite finishing the game and completing everything it has to offer (with a platinum trophy to prove it!), I could not point you to any particularly memorable bit of level design or combat encounter. There’s a blandness to the experience that puts me in a trance-like state. I could almost sleepwalk through each challenge without needing to focus too much or process any individual moment.

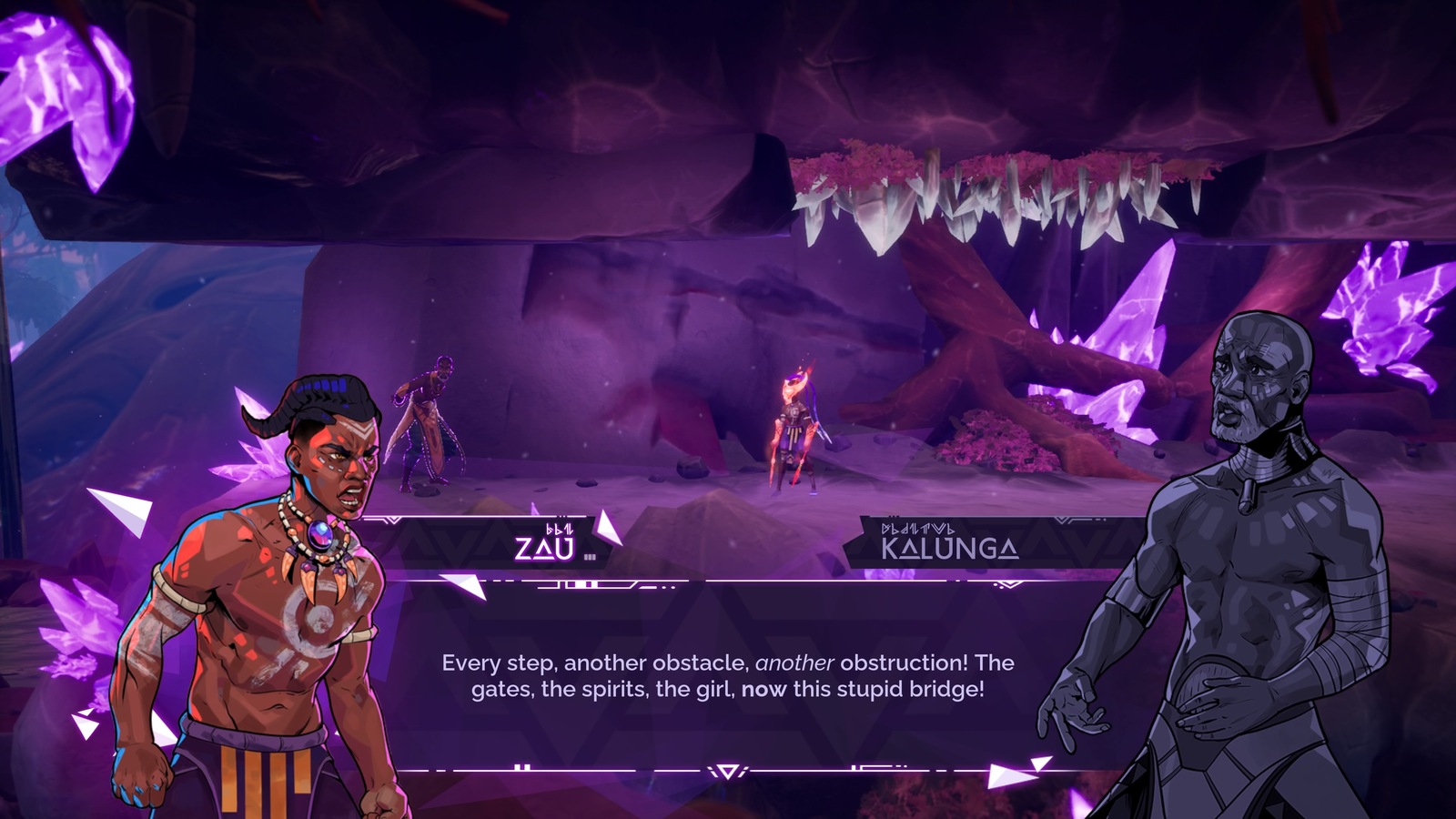

This relaxed design resulted in a disconnect from the emotional weight that Zau experiences throughout the story. There’s a moment early on where a bridge beneath Zau breaks, putting him on an inconvenient detour. In response, Zau emotionally breaks down and lashes out about how everything was going wrong in a way that felt totally disproportionate to me as a player. For Zau, this was a traumatic boiling point of horrible setbacks. For me, this was a couple extra minutes of uneventful platforming. This disconnect only grows as the game begins to tackle its deeper explorations of his fear, anxiety, and desperation. In its efforts to be as easy to enjoy as possible, Tales of Kenzera trades away its ability to fully convey the weight of the narrative it wants its players to experience.

That’s not to say that I think Tales of Kenzera needs to be brutally difficult or something, I just don’t think that the game should be painless, either. There needs to be some kind of friction or challenge to keep you engaged and properly synchronized with Zau’s plight. This isn’t a problem exclusive to Tales of Kenzera; going back to other Metroidios, for example, I had a similar problem with Metroid Dread. That game clearly states its mission in its title: it wants you to feel dread. However, Dread makes similar concessions to Tales of Kenzera in that any death will simply send you back a few seconds to try again. With a system like that in place, how much dread can any challenge truly make you feel?

As is, Tales of Kenzera finds itself in a conundrum. It has a compelling narrative hook, and its overall visual direction and use of African culture as a backdrop for its setting gives it a distinctive flair. Even the core of its gameplay mechanics rests on solid enough ground where I’d hesitate to call it bad or even mediocre. Tales of Kenzera is good, but I think it’s undeniably missing something, and I suspect that something is the kind of tension that only video games can provide in giving weight to Zau’s journey. Just like parting with someone you love, I don’t believe a truly special game can be an entirely painless experience.