When you’re a resident of a little town of about 3,700, it’s unheard of to find anything local on the map of an award-winning board game. Yet there’s tiny Ripley, Ohio, on both the board of Freedom: The Underground Railroad and as a card in the game.

I live just north of Ripley in the same county. The Underground Railroad ran through my area too.

Hundreds of escaped slaves found a friendly abolitionists (such as John Rankin or John Parker) in the hills of Brown County, someone who could help them along the figurative railroad line, which was a set of pathways to Canada and freedom.

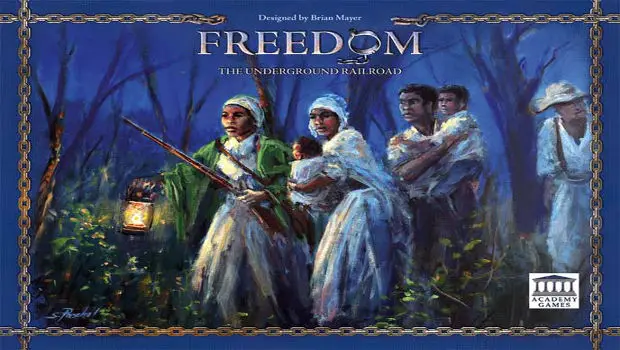

Freedom: The Underground Railroad is a board game about a difficult subject. More than 150 years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, slavery in America still rankles. That anyone would apply such a theme to a game might raise a few eyebrows.

But what a game this is!

All for freedom

The goal of Freedom: The Underground Railroad is for the players, who form a cooperative team, to shuttle a specified number of slaves from plantations in the deep South to freedom in Canada and generate support for the abolitionist movement. Those two victory conditions must be met in eight rounds. Meanwhile, slave bounty hunters traverse the northern states, attempting to catch any escapees, and slave traders in the South traffic in more and more human lives. Too many lost slaves, not enough support, and running out of time means a loss.

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the deck

The sturdy 13¾ x 10 x 2¾-inch box holds:

- 1 map/token game board

- 96 wooden slave cubes

- 52 Abolitionist cards

- 18 Slave Market cards

- 6 player role cards

- 6 player role mats

- 4 double-sided Victory Condition cards

- 27 Conductor tokens

- 17 Support tokens

- 13 Fundraisiing tokens

- 5 Slave Catcher markers

- 2 Slave Catcher dice

- 1 lead player lantern marker

- A pile of money tokens, in 1s and 5s

- 2 player aide sheets (condensed rules)

- 1 rulebook

[singlepic id=20019 w=620 h=350 float=center]

A promotional Abolitionist card deck from Academy Games, and offered through BoardGameGeek’s store, adds 18 more cards.

The game board is a sprawling six-section gatefold split two-thirds map and a third token/card area. The attractive graphic design channels the style and typography of the era. Even the token/card area resembles a tabloid newspaper circa 1850.

The card art features black and white lithographs, photographs, and engravings of the time, which boosts the historical feel. Each abolitionist card is tied to the three periods that comprise the game, 1800-39, 1840-59, and 1860-65. At each card’s bottom is a sentence or two detailing why that card’s featured person, place, legislation, or event mattered–both for good and for ill– in the fight to end slavery.

The cardboard pieces are of average quality for a game of this price, and the wooden cubes, which represent the slaves, are nicely done in a tasteful clear stain. The entire package looks and feels on par with many better board games today, but no components stand out as exemplary.

Some may note that online images of the game often feature tall, colorful, wooden prisms used for the Slave Catchers. These were Kickstarter exclusives. At one point, the game was a downloadable “print & play,” but it transitioned to Academy Games, which launched a Kickstarter fundraising drive to finance the production. The non-Kickstarter version lacks these prisms, relegating its buyers to less impressive Slave Catcher tokens. Too bad, because the prisms tower over the board and lend gravitas as they peer down on their human quarry.

Follow the drinking gourd…

The game plays over the course of eight rounds. Players win if

- they move enough slaves to Canada to satisfy the number listed on the Victory Conditions card, AND

- purchase all the available Support Tokens, AND

- finish the round without losing.

They lose if

- they exceed the limit of the Slaves Lost track on the Victory Conditions card, AND

- they fail to win before the end of round 8.

There are six player roles and cards in the game: Agent, Conductor, Preacher, Shepherd, Station Master, and Stock Holder. Each has a special ability that can be used every turn and also one that can be used once per game (consult the rulebook for details). Each also collects a small stipend during the Action Phase.

[singlepic id=20018 w=620 h=350 float=center]

The left third of board is broken into the three periods mentioned earlier, each with a player-number-determined set of Support ($10), Conductor ($2/$3/$4), and Fundraising (no cost) tokens. Each period also has its own deck of Abolitionist cards with general use (resolved immediately), reserve (held and resolved anytime afterwards), and opposition. These last cards complicate matters, limiting positive player actions or preventing them entirely, and a set number of them are shuffled into each period. Cards are dealt from the 1800-39 deck to seed the row of abolitionist cards in the five slots, which have costs (from right to left) of $1, $1, $2, $2, and $3.

Each round has five phases:

1. Slave Catcher Phase – Roll and resolve the Slave Catcher dice. One die has the five hued shape slave catcher tokens represented, while the other has 1-3 white arrows (move the slave catcher westerly by the number of arrows shown), and 1-3 black arrows (same, except easterly). The sixth face on the die is a walking slave–no slave catchers move. If the moved slave catcher ends its move on a space on the board occupied by a slave, that slave is returned to the current Slave Market card and must be placed on an open plantation space or ends up as Lost.

2. Planning Phase – Players can take up to two Support, Conductor, or Fundraising tokens from any active period on the board, paying any costs. Support satisfies a winning condition, Conductor allows slave movement, and Fundraising lets the player who later plays it collect $1 for every escaped slave in a southern town marked green. These tokens can be played in the Action Phase.

3. Action Phase – A player can do all or some of the following in this phase:

- pass all other actions in the phase and only collect money

- play up to two Conductor and/or Fundraising tokens

- buy one Abolitionist card (and resolve it if possible or desired)

- use the player role’s benefit ability

- use the player role’s once-per-game special ability

4. Slave Market Phase – Move all slave cubes on the active Slave Market card to open plantation spaces. Any slaves in the market that cannot fill an open space become Lost and are moved to fill open spaces on the lost slaves area of the Victory Conditions card. That Slave Market card is discarded, the rest slid down, and a new card is added and filled with the listed number of slave cubes. When all eight of these cards are exhausted, the game ends.

5. Lantern Phase – Discard the farthest right Abolitionist card, if still on the board (the farthest two in a 1-2 player game). Slide the remaining cards to the right to fill in the empty spots, and add cards from the active period deck. Give the lead player token to the next player in order and start a new round.

To complicate the movement of slaves when a Conductor token is played, if the slave ends movement on a town/city that connects to a trail marked with a correspondingly-hued Slave Catcher token, that Slave Catcher moves one town/city closer to that slave. If the Slave Catcher and slave end up in the same space, that slave is caught and moved to the active Slave Market card.

Some towns and cities on the board have a dollar value attached. If a slave ends movement on such, the movement garners the financial support noted. Most towns can hold one slave only, but some larger cities in the North can hold up to four.

In which Eliza flees across the frozen Ohio

This is a cooperative optimization game. The best-known game of this type is Z-Man Games’ Pandemic, in which the team works together to fight a global virus epidemic. Think of Freedom: The Underground Railroad as a step up from Pandemic, with deeper play and a little more to manage.

Deeper play is not a result of harder rules. In fact, the rules for Freedom are intuitive and easy to grasp. One round of play, and most people will grok it.

Where is the depth? In the optimization of actions. People with a background in systems theory will love Freedom, because it’s all about logistics. Finding a balance between slave movement, fundraising, card selection, timing, special role actions, negative and positive card functions, and countering slave catcher travels is a delicate dance that could go two-left-footed at any time. What makes this even more compelling is that the events of the game really happened.

And it’s hard. This isn’t a game for people who frustrate easily. Add in an emotional theme, and feelings run strong for players. I had more than one gamer balk at playing because they were unsure they could handle the theme. Others hesitated because it’s historical.

The historical notes on the bottom of the Abolitionist cards add a real connection to the past and are enlightening for those with little knowledge of 19th century happenings in America. The rulebook further expands the facts behind those people, places, and events that drove the abolitionist movement.

Like another historical game I loved, Lewis & Clark: The Expedition, the cards in the game contain associated actions that reflect the real-life abilities or outcomes of the person, place, or event the card depicts. The Dred Scott Decision forces some slaves back to the plantations. The 1850 Compromise damages fundraising abilities. Harriet Tubman can move four slaves and ignore slave catchers. The sympathetic speeches of Frederick Douglass net all players $4 each to fight for the cause. Players feel like they are caught up in the era and the emotionally-charged issue of slavery.

All those feelings, the history, the educational aspect, and the team play of Freedom: The Underground Railroad are what make it a great game.

Free at last!

Many cooperative games can be played solo because the opponent is the “engine” of the game itself. I played this both solo and in a group, and the experience was similar, though playing with others brings out a positive groupthink that will likely boost chances of beating the system.

I’ve heard reports that this is a difficult game to beat, but I played a solo effort that revealed one aspect of the game some picky gamers may not like: the hand of Providence–or luck, as some today call it.

[singlepic id=20020 w=620 h=350 float=center]

I was in a bad position on the board, with rounds running out quickly. I had all the Support tokens I needed to win, but the board was jammed with slave cubes I could not move–especially into Canada. That’s when the John Brown card came out. I was able to buy this card with my last dollar, and it not only moved several slaves into Canada, but it also allowed me to draw an Abolitionist card blind from the deck. The drawn card proved to be Abraham Lincoln, sealing the win by moving the last slave I needed across the border.

That was almost the perfect 1-2 punch, and it happened because of the random nature of cards. Dice also contribute to the randomness.

That said, almost all cooperative games contain a random element. Sometimes it works for the team, and sometimes against. But that’s real life too, and I can imagine situations in 1859 when an escaped slave happened to avoid capture through a series of uncontrollable events: the ferry boat that stayed on the shore a minute longer than normal, or the abolitionist who delayed his travels by one day, and was available to help a runaway who otherwise would have had nowhere to turn, no friendly home in which to hide.

On the other hand, good fortune can be fickle, and everything may go pear-shaped for the forces of good. In a group game, a series of negative card draws we could not clear stymied both movement and money. We lost two rounds before the game was to end. Ouch.

What Providence also adds is replayability. The different player role cards stir the mix too. That said, one player remarked that the lack of a player piece on the board for her role felt odd and distancing. Also, each turn felt “same-y,” with little variance.

No two games of Freedom will play identically, though. Because the game is more expensive than some, this improves its value.

The game plays quickly, never overstaying its welcome—unless all the players fall into analysis paralysis while trying to optimize every turn in the game. The complexity of the game makes it harder for one player to assume control of other player’s turns (the dreaded co-op alpha gamer), but players will still need to discuss each turn how their unique role skills will best work.

Freedom scales well from one to four players and shows excellent balance at all player counts. That it’s designer Brian Mayer’s first game is extraordinary.

Any good cooperative game is a rollercoaster of huzzahs and “oh, crap!” laments. Freedom: The Underground Railroad amplifies this by its theme. It may look like a little block of wood on the board, but that cube represents a person. Each person lost carries meaning, much like the real life events of the slave trade and it’s human toll.

This game recreates that feeling, and that’s an amazing accomplishment. Freedom: The Underground Railroad was a Top 10 pick for best games of 2013 by many board game experts, and with this 2014 reprint, you and your gaming friends can find out why.

An engaging, challenging winner.

Game Name: Freedom: The Underground Railroad

Designer: Brian Mayer

Publisher: Academy Games

Year: 2013

Players: 1-4

Ages: 10+

Play time: 90 minutes

Mechanics: Cooperative area control, Point-to-point movement, Variable player powers

Weight: Medium – “More challenging, but relatively easy to learn to play”

MSRP: $69.99***

Great

A sensitive and historically educational treatment of a difficult subject (slavery in 19th century America), Freedom: The Underground Railroad may be the best cooperative board game ever published. The difficulty in winning reflects the real-life struggle of escaped slaves to make their way to freedom in Canada. A challenging experience for thinking gamers and their families.

Pros

- Outstanding cooperative and solo play

- A history lesson in a game; highly educational

- Challenging, both as a game and as an experience

Cons

- Some find the theme unsettling and losing emotional

- Historical games can be a hard sell to some

- Hardcore gamers may object to “Providence”