As hard as it may be for some of us to believe, Dungeons & Dragons has been around for fifty years and D&D’s fifth edition has been out for ten. Taking over from fourth edition after an extensive public playtest and development, the new fifth edition was a large departure from fourth and a step back towards third at the same time. While finding a new audience and poised to grow through the onset of Covid, fifth edition has plugged along with a continuous stream of books – providing players and DMs alike with tons of content and ready-made adventures to keep their groups busy. The game has expanded beyond the initial offerings of the Players Handbook that came out in 2014. With the implementation of the Unearthed Arcana, Wizards of the Coast (WotC) opened up the ability to playtest content as they developed it and over time address issues with the rules. We now are seeing the changes that a decade has wrought in the form of a new set of basic rulebooks. WotC maintains that this is not a new edition, nor is it a partial edition (a la 3.5), but rather, an update to fifth edition. So we will now have the 2014 rules and the 2024 rules of fifth edition. With planned releases of the updated Dungeon Master’s Guide and Monster Manual on the horizon, WotC has led into the updated rulebooks with the Player’s Handbook. Concurrent with the publication of the Player’s Handbook hardbacks (there are two different covers), the D&D Beyond digital copies are coming available as well. Let’s dive right in and see what the fuss is all about.

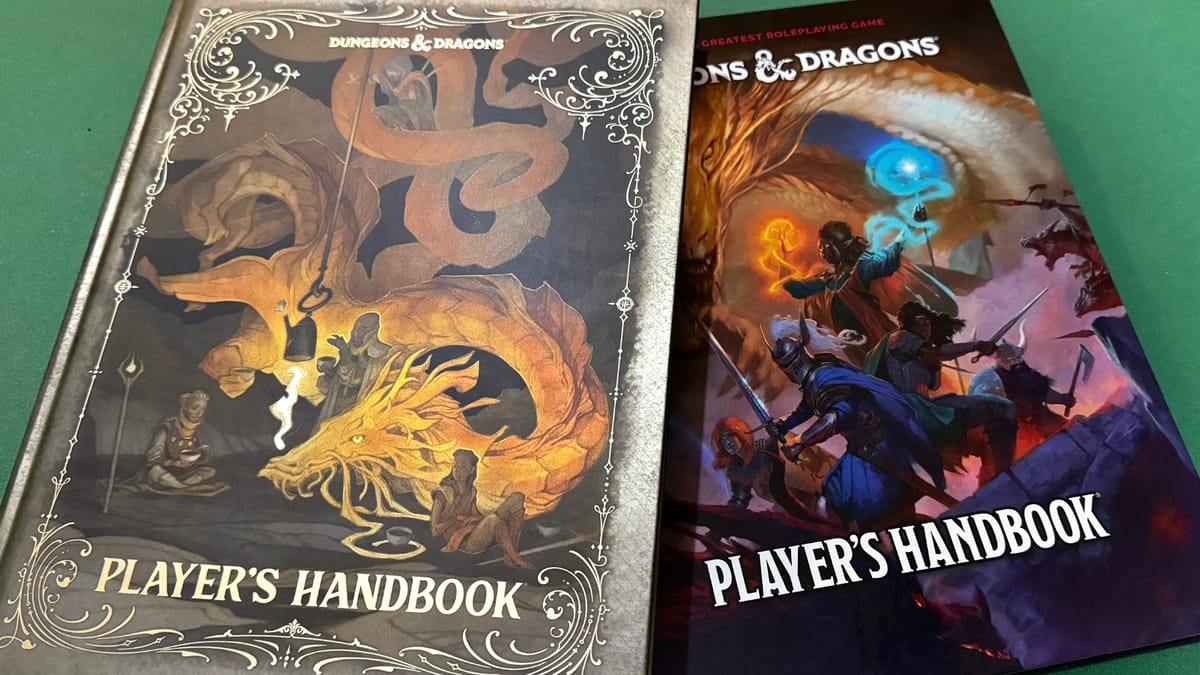

Standard Cover of the 2024 Fifth Edition D&D Player’s Handbook

Like many of the publications for fifth edition, this new Player’s Handbook comes with two different covers. The standard cover has almost the same format, font and spine as the rest of the edition’s books, but there are slight variations. The most noticeable is the reversing of the colors on the spine. While the 2014 era books have black spines with the Dungeons & Dragons logo at the top in a black splash, the 2024 era Player’s Handbook has a red spine with a black splash at the top. It fits in nicely on the shelf, but stands out right away as different. We know that the Monster Manual and Dungeon Master’s Guide will feature the same updated style standard covers, but we don’t know if that will be the format for other releases post 2024 rules update. The cover art for the standard cover shows a gold dragon hovering over an adventuring party facing off against what appears to be another dragon low in the foreground. It’s a beautiful piece of art by Tyler Jacobson (who did the artwork gracing the 2014 cover as well) that just feels like a D&D adventuring party. The alternate cover, by Wylie Beckert, shows an adventuring party relaxing with some tea and a gold dragon. This scene, which evokes the down-time between adventures, gives us a view of the revamped gold dragon which we’ll see more of when the Monster Manual comes out early next year. Another beautiful work of art, this is another outstanding alternate art cover that looks beautiful on the shelf. Like so many of the other fifth edition books, these covers look great.

A fighter.

After you finish admiring the cover art, you have to crack open the book and take a peek at the contents. While we can surmise that we are looking at revised content from the 2014 Player’s Handbook, on the copyright page just before the table of contents, there is an entry that tells us the book also contains revised content from Xanathar’s Guide to Everything and Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything. We also know from interviews with the lead designer, Jeremy Crawford, that most of the new content in the book was seen in one form or another via Unearthed Arcana. Right away, players familiar with the 2014 book will notice the content has been reorganized. This is the first big plus from my perspective. After struggling for years with the unintuitive structure of the 2014 book, this new structure is a welcome change. This book is sixty pages longer than the last and chock full of information. This is reflected in the three columns in the table of contents. I will note that the table of contents in the 2024 book has a slightly smaller font than the 2014 table… but the font in the rest of the book appears to be slightly larger than the 2014 book. The new book seems to have more artwork as well. So, does that mean the extra 60 pages don’t actually contain more information? It’s hard to say for sure with all the changes, large and small, but in the end, even if the extra 60 pages doesn’t provide expanded content, the additional artwork and easy-to read font are nice benefits. I can say that the new organization is better than the 2014 handbook – mine is a mess of so many tabs that I’m not sure they help. I don’t think I’ll be needing nearly as many tabs in this handbook, if any at all.

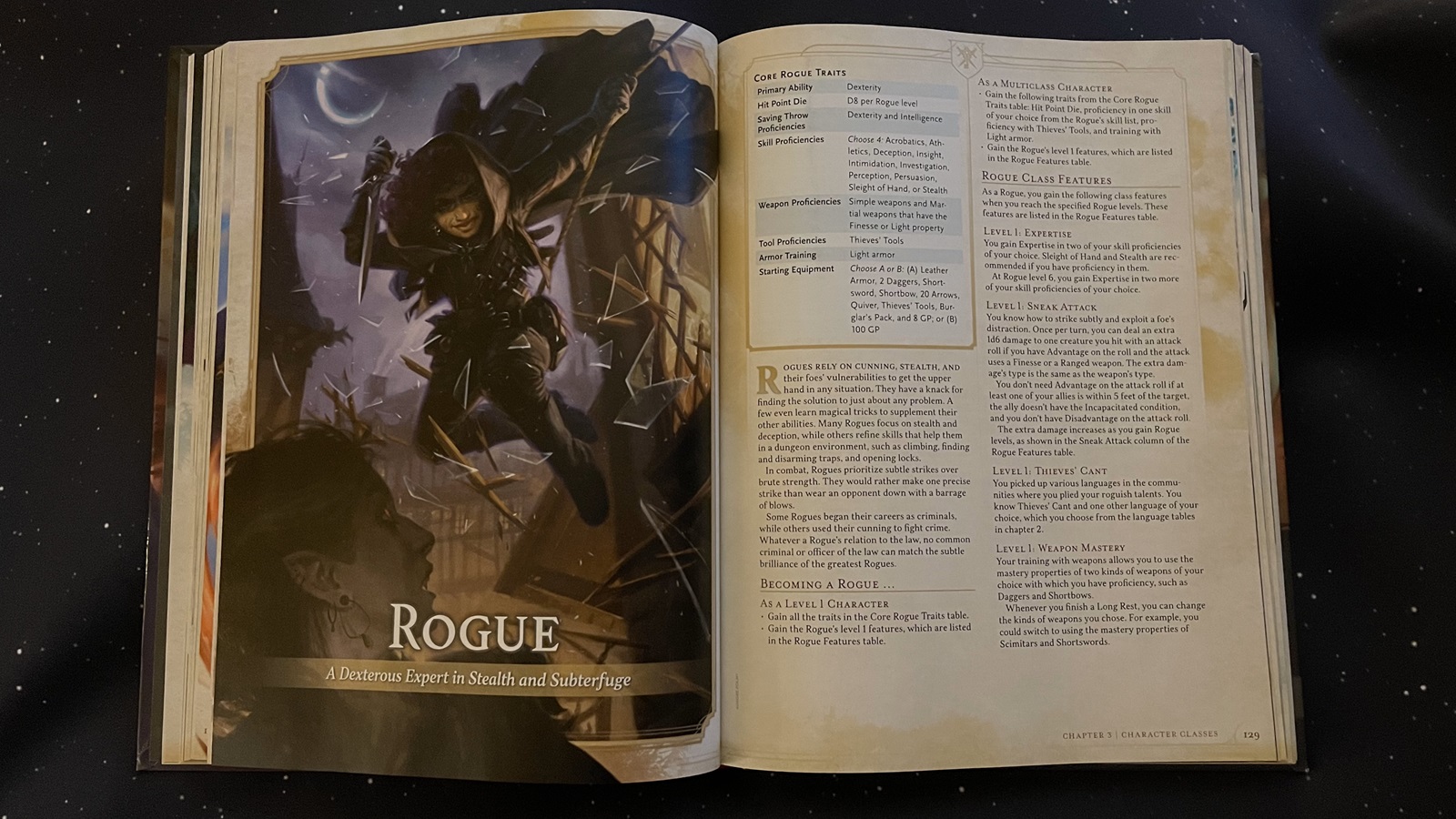

The start of the rogue entry in the character classes chapter.

The book jumps straight into how to play the game in chapter one. The sections of this chapter start players with an overview of the roles of the dungeon master and the players, what game play is like, then dives into a description of the mechanisms of the game. This is accompanied by examples, called out in boxes, that are taken from a sample game session. The rules explanations are clear and concise. A lot of the crunchy bits have been moved to a new appendix, the Rules Glossary, which essentially replaces or expands on the Conditions appendix from the 2014 book. The nice part of the rules glossary is having all the key words piled into one spot. If you want to know the basic rule, look in the glossary, if you are looking for an expanded explanation, that’s in the chapter that discusses it. I’ve already found the rule glossary useful for a quick look-up of information. For those with access to D&D Beyond, you can always quickly search for a rule, but if you are relying on the hardback book, then this glossary is a time saver. It also makes the main chapters of the book flow better. You can read through the rules and flip back to the glossary to get more details with ease. Experienced players will have to get used to some terminology changes, such as the monk’s ki being changed to focus, but most of the changes aren’t too hard to pick up. This opening chapter eases new players into the game and helps them understand what they are doing which is essential going into chapter two, character creation.

The character creation chapter covers the process of creating a character step-by-step. There is a bit about level advancement, a discussion of the tiers of play (saving a village versus saving the world) and a nice table of a hundred trinkets that your character can start with to inspire your roleplaying. There is a good summary of multiclassing here and a handy sidebar that tells players how to use backgrounds and species (no longer races) from other 2014 era books with the new ruleset. This is important because one of the changes in this update takes ability score modifications away from the species and gives it to backgrounds, more on this later. After this short chapter, we jump straight into one of the biggest chapters in the book which cover character classes.

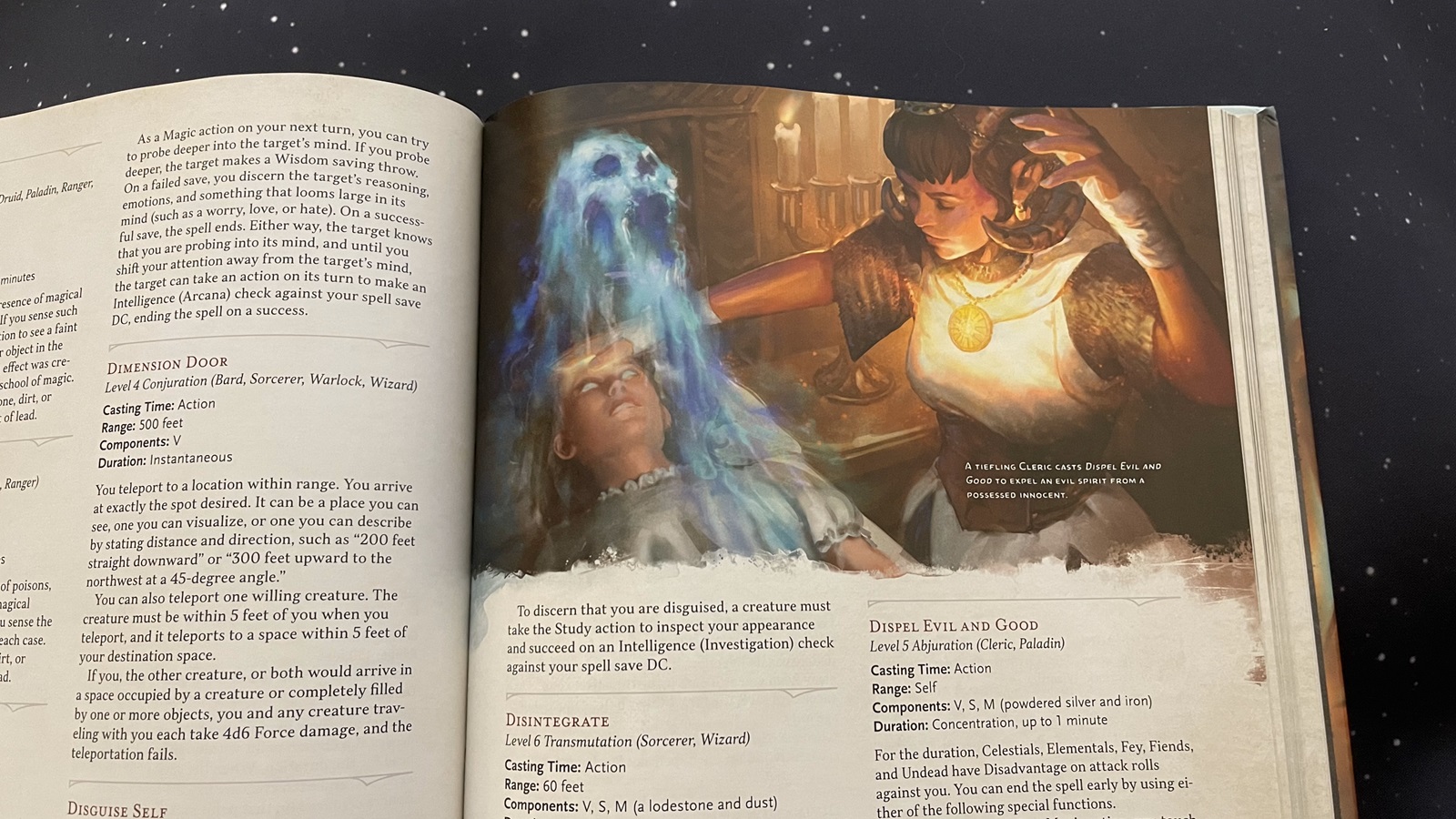

Illustration of the Dispel Evil and Good spell.

As in the 2014 book, the same twelve classes appear in this handbook, but each has four subclasses. The classes have all been reworked, some extensively. A primary theme that runs through the revamped classes is access to iconic class abilities early on and the ability to use them more often. It’s here that we see content from Xanather’s, Tasha’s, and Unearthed Arcana. The ready access to four subclasses for each class is very nice. I find the available selections to be pretty good. The spell lists for the magic using classes are listed right with the classes in this chapter. I find this convenient, although it doesn’t really reduce the amount of page flipping you have to do. You have to look at your spell list, then flip to the spell description to read about it still, but at least the list is right in the section with the class. There are plenty of tweaks to the classes that make them more… playable. For instance, barbarians can regain a use of their Rage feature with a short rest and the Rage can be extended now as a bonus action and it can be maintained this way for up to ten minutes. This enables Rage-based abilities to be used outside of combat and for the barbarian to maintain a Rage through a lull in combat. There are a few subclasses that I am not enamored with, such as the bard’s College of Dance, but just because I don’t plan on playing doesn’t mean that there aren’t plenty of people who’d live to have a dance-fighting bard. I do love the artwork that accompanies each class and subclass. This chapter gives players plenty to work with and tons of options. This is where this new handbook really shines.

A background and its accompanying illustration.

The next chapter deals with character origins, which amounts to backgrounds and species which used to be called races. Previously, your character’s race (species now) affected your ability scores while your background gave you some proficiencies and equipment along with roleplaying options. In the 2024 book, your backgrounds provide ability score adjustments, feats, proficiencies and equipment. Species still provide things like dark vision and dragonborn breath weapons, but no ability score changes. I’m OK with this change. Having species affect ability scores tends to push certain species towards specific classes. Now, you can choose whatever species you want and then select a background that supports the class you want to play. There are three ability scores listed with each background and you choose to apply a bonus of 2 points to one and 1 point to another, or one point to each of the three. So if you choose the soldier background, then you’ll get three bonus points to spread in strength, dexterity, or constitution which supports martial classes and your character’s species is immaterial. From my perspective, this is fine and it makes sense with the overall trend in D&D rules development that has made character creation more flexible and fluid throughout the life of fifth edition. With these changes, you can still make a dexterous halfling rogue, or a brutal dwarf barbarian… or vice versa. A lot of space was saved in this section by dropping the personality traits, ideals, bonds, and flaws from the backgrounds. I don’t miss them as part of the character creation process. I do think they are useful for players to help inspire character creation, rather than just staring at a blank space and trying to dream up a personality for your character, but this is where I think keeping a copy of the 2014 book around would prove useful. There are a few changes to the species in this book that stand out. There are no half-elves or half-orcs in here. Instead we are given aasimar, goliath, and orc as options. I like the new options, but losing the half species is a bit sad. You can still play them from the 2014 rules, just adjusting them, but anybody picking up this book as their first one won’t see half-elf as an option… which is weird to me.

A familiar cast of characters?

The feats have been updated and promoted from a customization option to a standard part of character progression. Chapter five details the feats. The first general feat is Ability Score Improvement. This makes sense – just like in the 2014 rules, part of character progression is the choice to periodically improve ability scores or gain a feat. However, rather than presenting feats as an option you can take instead of ability score improvement, the ability score improvement is now a feat. The odd thing is the feature column in each character class’s progression table doesn’t just say, take a feat at a certain level (usually the first feat is at fourth level). They all say, “Ability Score Improvement” in the table, then under the description for that feature it says you gain the Ability Score Improvement or another feat of your choice. This feels like a part of the old rules that only got half updated.

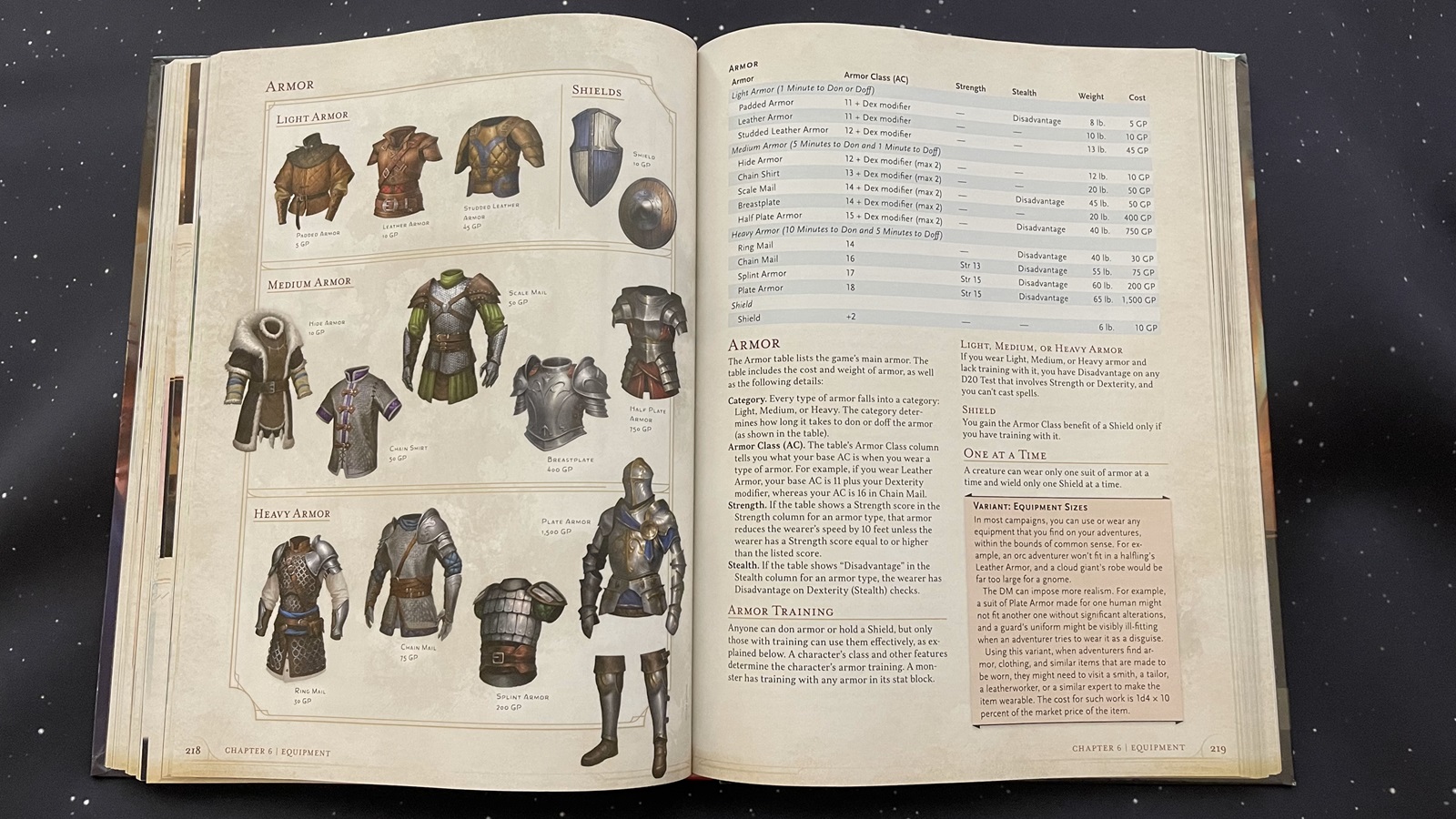

The equipment chapter is well illustrated, with pictures for every weapon and piece of armor, which is nice for someone that isn’t sure what a halberd or a glaive is… but does make you wonder what the difference is between a pike and spear – since they are strikingly similar in the illustrations. Of note, every weapon now comes with a “mastery property” that certain classes can use as part of their class features. The mastery properties are not unique to each weapon, but they do give the weapons more distinguishing characteristics and add flair to the martial classes that can suffer from the dullness trap of, “I swing my sword again” during a protracted fight. The equipment tables also include a substantial entry in the tools section. The nice thing about all the tools is that they now correlate to specific things that can be crafted, and there is a short section on crafting. So now, if you own woodcarver’s tools, you know what you can carve with them, how much it will cost, and how long it will take. So not only do you get the flavor of owning the tools, you get some tangible results when you use them.

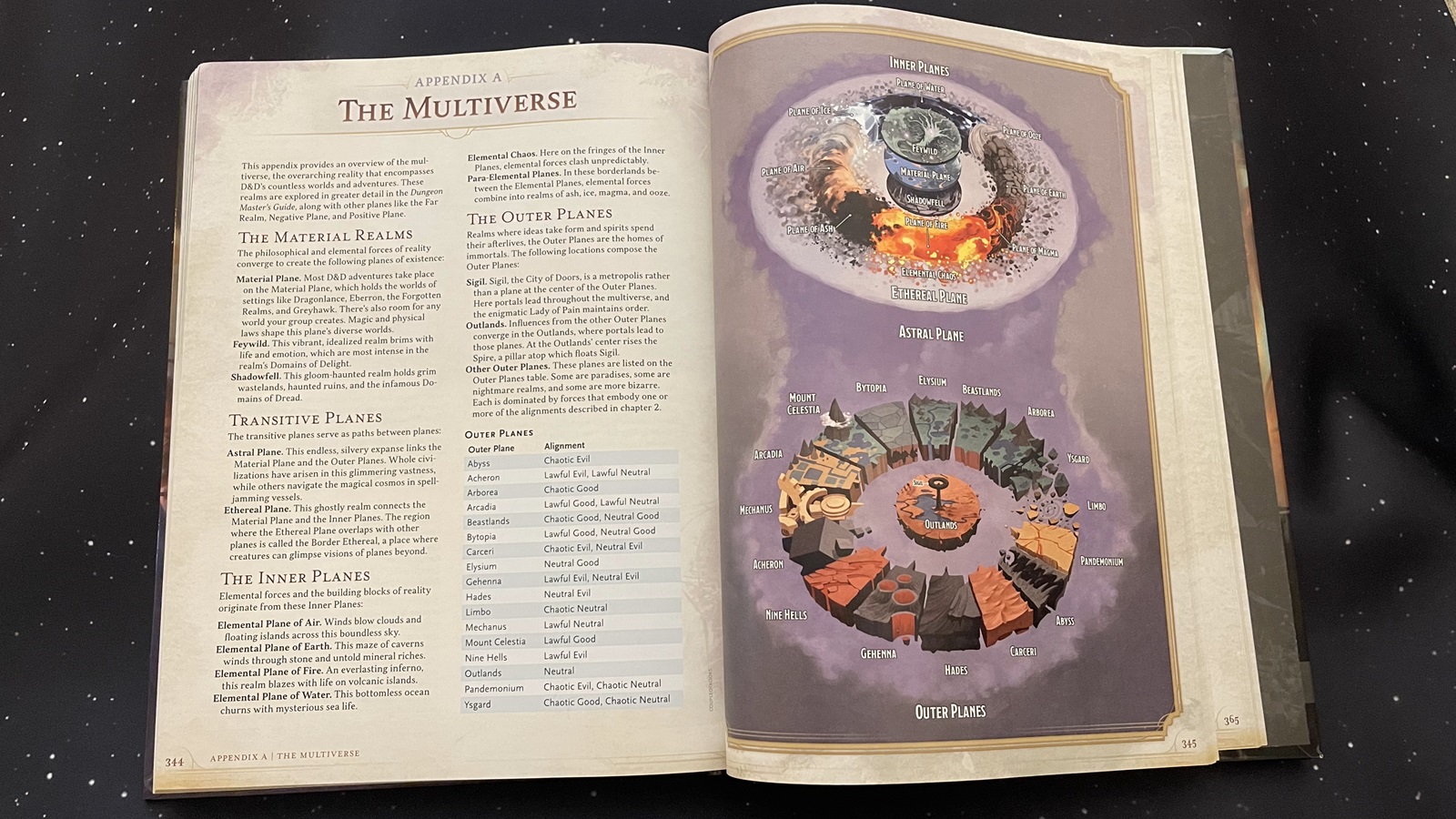

The new entry on the D&D multiverse.

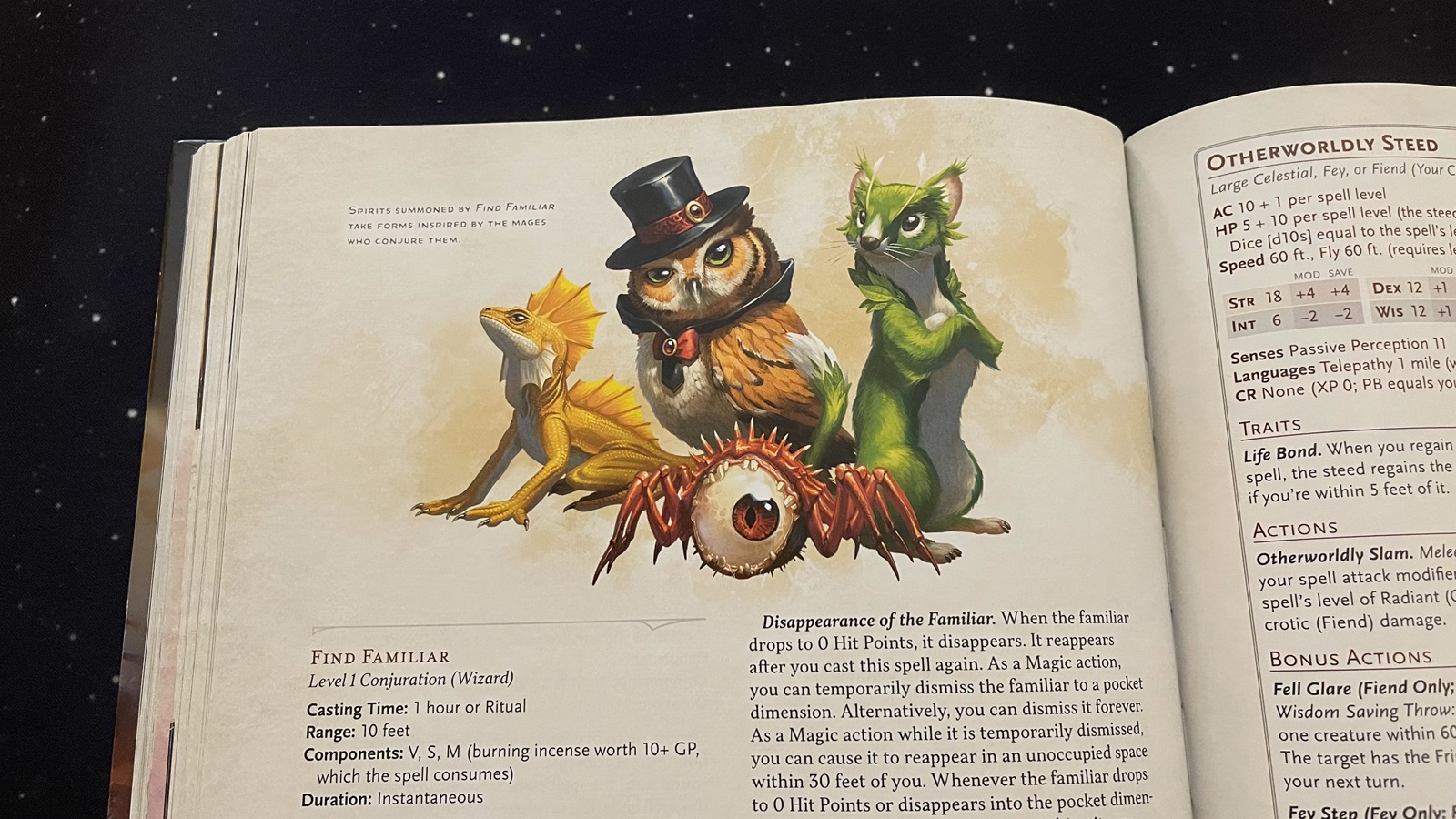

Chapter seven is a huge collection of spells. There are a lot of little tweaks to various spells in here. The main change that stood out to me is the revamping of the summoning spells. All of the summoning spells now summon spirits that take the form of whatever is being summoned. So if you cast Summon Aberration to call up a Mind Flayer, you don’t get an actual Mind Flayer, you get an Aberrant Spirit in the form of a Mind Flayer with the stats from the Aberrant Spirit stat block. This change applies to the summoning spells, and variations on it including abilities that summon creatures – they’re spirits. I don’t think this affects gameplay that much, but it potentially clears up any issues people may have had about where those summoned creatures came from and what did it mean when they died in your service. Not sure that was a concern people had, but they won’t have to worry about it now.

Armor selections from the equipment chapter.

The book winds up with appendices that provide a very brief overview of the multiverse, a list of creature stat blocks for polymorphing etc., and the rules glossary I mentioned earlier. All three appendices are useful, but I do miss the lengthier section on the multiverse that was in the 2014 edition. This is especially interesting because there are a few more references to the multiverse scattered through this book than previous player’s handbooks. For instance, in the language section, there is a reference to Common having originated in the city of Sigil. In another example, Sigil’s Lady of Pain is mentioned in the text of the Wish spell. With these references in the book, I would have liked to have seen more than two sentences on Sigil and more than two pages in the multiverse appendix. That’s very little space to use for such a big concept. There is not any information about the gods of the multiverse, which would be useful for divine spellcasters to reference. I realize that many DMs provide their own homebrew, but a lot of DMs also use the published settings. A summary of their gods in this book would have been useful. The other thing that stood out to me was the change to the walking speed of the shorter species. I’m not sure why halflings, gnomes, and dwarves sped up to the same pace as humans, elves, etc. while goliaths are five feet faster. It seems like the idea was to make the party move at the same rate, since a party with a halfling has to slow down to the halfling’s pace… but I don’t know how much that really affected game play. Were there a lot of complaints that the slower walking speeds were slowing the game down? I don’t know if this change makes that much of difference and I’m feeling like some flavor was lost there. These are just quibbles; nothing in this book is egregious or unduly frustrating. It’s D&D Beyond counterpart is implemented well and they did a great job of incorporating a toggle into user options to allow you decide whether to enable or disable the 2014 rules.

D&D Player's Handbook 2024

Excellent

This is a beautiful book with fantastic illustrations throughout. The organization is a huge improvement over its predecessor, and the changes overall seem well thought out. An argument can be made that this is really 5.5 or maybe even a stealth sixth edition, but I can see why WotC chose to call it an update. Many of the plethora of little rules tweaks and adjustments may slip by without much fanfare or notice, but the changes to the character classes will be meaningful and probably translate directly to more effective characters and tougher adventuring parties. But changes to the characters don't really change the rules that much, and the changes to the rules aren't that extensive. I am looking forward to seeing characters built in this book in a party to see how things change. Are they going to be as much tougher as it seems? I think so. While I may not love every character class option in here (dancing bards?), I love having all forty-eight subclasses available. You cannot go wrong buying this book, but if one player in the group wants to use the 2024 players handbook, then everyone should use it. The changes made to the classes are substantial enough that a character from the 2024 book is going to be better than the rest.

Pros

- Excellent organization

- Four subclasses for every class

- Rules Glossary is super helpful

Cons

- Loss of half-elf and half-orc

- Not enough information on the multiverse and its Gods

- You cannot mix characters created from different books in a party