I could never really nail down the complete game of chess. The early and mid game, when the board still has a reasonable count of pieces and options are somewhat limited, I can reason out how to navigate exchanges in my favor. But I always fall apart in the late game, when I’m supposed to be galaxy brain-style keeping a whole probability tree of twenty possible game states in my head based on my opponent’s remaining options on an open board. I legitimately don’t understand how people don’t. Match of the Century is a chess game, in that it’s a game about the ‘72 championship between Spassky and Fischer, but it most definitely isn’t chess. My best attempt to nail down a familiar concept here would be the lovechild of a card-driven wargame and chess, but due to some brilliant design decisions, it’s leagues more approachable than its parents.

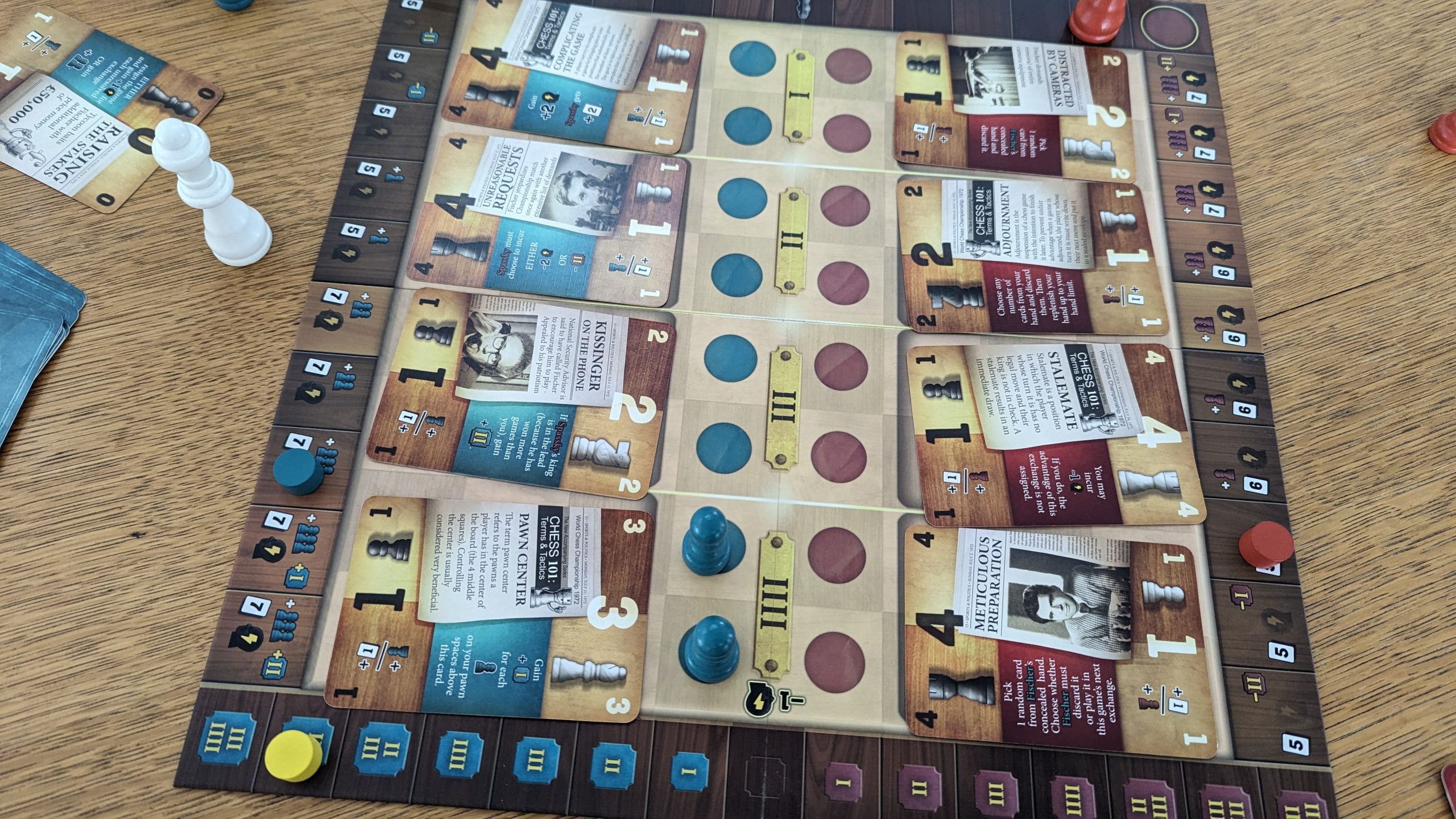

I generally loathe doing rules explanations in my reviews since PDF rulebooks exist and that’s Rodney’s gig; I’m certainly not besting the god-king of teaching board games, but I’m gonna this time cause I’d wind up doing most of one while I explain why I like this game anyway. Both players are in a race to win six games, Match’s rounds, through a series of exchanges, which function similar to turns and are also mirrored spaces with strength 1-4 on the board. Spassky, as the defending champion, plays white in the first game and determines the first exchange. Playing into an exchange is, like most of this game, simultaneously simple and crunchy: if there’s already an active one, you have to play one of your cards as a piece of the color you’re playing that game into it, along with up to two pawns from your active pool. After both players have played their cards, you’ll resolve the exchange by comparing strengths (numbers on the cards plus one for each pawn), resolving the loser’s card ability, moving the winner down one space on their mental track, and finally moving the advantage token that exchange’s strength towards the winner. If the advantage is now further to their side than the rest of the points available on the board, the game ends early as a victory for that player. Otherwise, they choose a new exchange and that game continues until a victor is determined. During a game, your position on your mental track won’t have much impact, but when you’re setting up a new game, you’ll feel the hurt if you haven’t been managing your mental exhaustion when you reconcile your hand with the size on the track, gain pawns to your pool, and even adjust the initial advantage. The tracks and decks are asymmetrical: Fischer’s mental health is more fragile given that he’s, yanno, Fischer, and his deck is more shaped around playing from behind, while Spassky’s leans towards taking an early lead and maintaining it, but the same fundamentals apply to both sides. As much as asymmetry has been a marketing-friendly word since Root came out, I’ve found hard asymmetry makes teaching and even playing a game a chore; a soft asymmetry where the base mechanics stay the same between players tends to smooth out the whole experience for everyone.

Okay, so far I’ve covered the easy to learn but what about the other half of everyone’s game phrase, difficult to master? Match’s first layer of difficulty slaps you right in the face with the contradiction inherent in its design: that you need to win exchanges to win games, but you don’t want to win exchanges because they’ll make you worse in later games. So obviously you tank the first few games so you can just sweep your opponent, but then again they may be trying to do the same thing and then again you’re playing a race to six so maybe giving your opponent three free wins isn’t the best idea? Next up you’ve got learning how Fischer and Spassky want to play, because as much as you can in theory just use Fischer’s massive initial hand to just dominate the opening game, you’ll be immediately tanked by his fragile hand size going down the mental track leaving you with barely enough cards to play into every exchange. There’s a myriad of other things that make Match simultaneously easy and tough, like the obscene amount of game states that the cards and playing anything off-color as a one strength pawn can provide, or just deciding which order you want to take your exchanges in if you’re winning them.

But as much as I’ve sung Match’s praises, I’ve also got some critique of facets that make this game not work for everyone; mostly all results of its strange not-quite-a-CDW nature. Those decks that keep Match from being deterministic while still maintaining a heavy influence of skill? They also necessitate a familiarity with those decks for the game to not create feel-bad moments. Both players have access to cards that are situational blowouts, which is fine, that’s in a lot of card based games, but the thematic connection to the effect (at least to me) is so thin that it doesn’t work unless you’re prepared for them. In War of the Ring, if the Free Peoples player gets a free kill on an unguarded Sauruman with an ents card, that works thematically. Fischer not getting the advantage he needs in an exchange because of Spassky’s stalemate card just kinda doesn’t make sense. I get that they were running out of chess terms and forcing a whole game draw as a card effect would be insane, but there’s a disconnect that makes the punch to the gut hit a little harder. There’s also the production, which is just adequate except for the perplexing idea to switch the sides that cards’ game text and flavor text are on between black and white cards. All in all, Match winds up being a difficult game to pin down: it’s a two-player goat and wraps in the 30 minutes on the box with my dad, simply above average and a smidge longer when played with a friend, but an absolute flop with others.

Great

Match of the Century may be your favorite two-player game that runs in under an hour. Is it mine? Depends on who I'm playing with.

Pros

- Deeper than it has any right to be

- Extremely intuitive rules

Cons

- Mediocre production

- Poor theming fails to soften the blows of cards when they foil your plans