I probably shouldn’t admit the countless hours I spent playing Rollercoaster Tycoon. I’d tweak my coasters for maximum thrill, and when that didn’t work I’d drop the occasional ungrateful patron off in the lake. In short, I was the tyrannical Walt Disney. So, when I got news about Unfair, I was ecstatic. Finally, a game based on building the greatest amusement park geared to keep the masses coming through the turnstiles.

Publisher Good Games is banking on that same “one more play” appeal of its computer cousin. The core of Unfair is about building attractions, upgrading them to attract more guests, and scoring victory points for the largest designs at game’s end. Players also earn victory points for completing blueprints, which require you to fulfill specific builds in your park. Coins also earn a victory point for every two left in your stockpile in the final scoring phase. It’s a straightforward scoring system, though you’ll need to do some math as the scoring for attractions can escalate quickly.

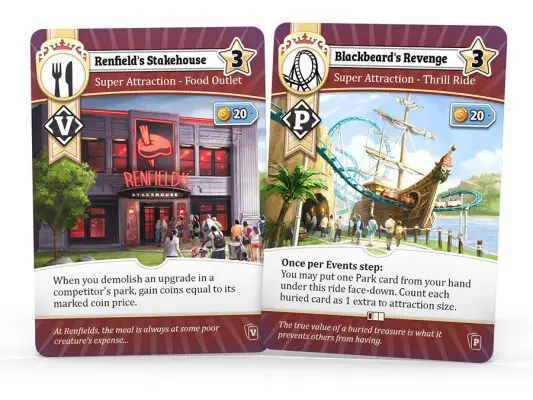

Card art is exceptional, and the card’s abilities are easy to understand.

The game has four different themes: Pirates, Vampires, Jungle, and Robots, and you pick a number of themes based on the number of players. All cards from the selected decks are shuffled together and each player will have access to all themes. Decks are then divided into different areas. Park cards contain attractions, their upgrades, and staff members. Event cards have dual abilities. One is a beneficial event for you, while the other has a detrimental effect on your opponent. A few showcase cards build super attractions that cost more but can draw in more customers. Finally, the blueprint cards and city events round out the card types available.

Players begin by drawing events and city event cards which affect everyone. Early in the game, they provide a bonus such as extra money. In the later rounds, city events hurt all players by reducing income or increasing costs. Effective planning in the first half of the game can offset the negative events in the second half. Regular player events are also played before turns begin and can have immediate or delayed results. The multiple actions on each event are reminiscent of card driven games.

The heart of Unfair lies in the park cards. You use money to purchase and place attractions in your park. Each attraction, whether it’s a ride, restaurant, or sideshow has a star value on it. The higher the star value, the more the attraction is worth in ticket sales at the end of each turn, and upgrades to that attraction can add further value. Specialty staff members can also add stars to your park and many provide additional bonus points at the end of the game. Parks are limited to fifteen stars that you can cash in for ticket sales each turn, but there’s no limit on the amount of stars your park can accumulate. Upgrades and resources allow for extra ticket sales, allowing you to earn more than the fifteen star threshold. Each thematic park deck comes with more cards than you’ll typically use in a game, so the replay value is extremely high.

Building bigger and better rides can score you some tremendous points but can also make you a target for sabotage.

Your park’s amusements score victory points after the eighth and last turn. Instead of using the stars to tabulate this, attractions score points based on the number of ribbons they have on them, which each attraction and upgrade has. Victory points increase as the number of ribbons increase. A ride with two attractions added score you twelve points, but an amusement with three upgrades score you sixteen. This makes for some rather odd results. Realistically, a park would garner more fame by having a thrill ride with a splashdown upgrade, but in game terms it would score fewer victory points than a restaurant with air conditioning and comfy seats. It doesn’t fit thematically. This could be solved by multiplying the number of upgrade ribbons by the base star value of the attraction.

Your personal game style will determine if you play a friendly game or get down and dirty, but both have some drawbacks. If you choose to play dirty, the game may bog down. Entire rides can be demolished or closed, and staff members can be stolen. These can be blocked by using other event cards, but the event cards end up feeling like they’re being held hostage. No one uses them to advance their parks because their holding on to them to block those inevitable gotcha cards. It doesn’t help that the city event cards that hinder players in the later rounds almost encourage subterfuge. I have nothing against a game that has mechanics where attacking your opponents is in play, but understand that this game can be unforgiving at times.

Contrarily, a friendly game could ruin diversification. Since a level ten attraction is worth more than four level threes, the emphasis in a passive game becomes building one great attraction while ignoring all others. Sure, I can upgrade the heck out of my Ferris wheel, but who goes to an amusement park for the Ferris wheel? Again, it’s a thematically problematic.

Either way you choose to play the game, there’s no avoiding how overpowered coins are in victory scoring. Granted, a profitable amusement park should be rewarded, but it shouldn’t be an overwhelming factor in winning. In one game, a third player was clearly trailing the other two. Their park had less than the maximum five attractions allowed. None of their attractions had over four ribbons. Yet, they managed to play a couple of events on the last turn that doubled their income and gave them another eight coins in the bank. The result was enough coins to earn nearly 40 victory points! Not only did they win the game, they won it handily as the other two players had worked hard to build impressive parks with little coin left over. The win felt cheap. Some of the negative city event cards push this style of play. When the spiraling costs card doubles the price of attractions and upgrades, the wise move is to simply collect loose change based on the number of rides you have. There’s no attraction or upgrade worth more than simply passing and taking a handful of coins for the entire turn.

I’ve mentioned all these annoyances, and that’s really all they are. I admit I came in with ludicrously high expectations, and that may have been the reason I came away from my first play a bit bewildered. Then, I played it again. And again. The more you play, the more you get an appreciation for how good the game is. The artwork captures the feel of an amusement park. The bright colors have a carnival appeal to them. The game’s mechanics work very well. Even the humor and festive nature of the game reflect a real amusement park experience. It’s certainly satisfying to expand and upgrade your park and watch the coin pile grow. There are quirks, undoubtedly, but If you loved Rollercoaster Tycoon or simply love theme park based games, then you could overlook the game’s flaws or even create your own house rules. Unfair may not be the perfect game, but it’s a really enjoyable one.

Designed by: Joel Finch

Published by: Good Games Publishing

Players: 2 to 4

Ages: 12 and up

Time: 60 to 150 minutes

Mechanics: Hand management

Weight: Medium Light

MSRP: $49 on Kickstart

Unfair

Great

Unfair's name is certainly apropos with its take that approach, but the game's customization allows you to be as friendly or as harsh as you want to be. While it isn't without a few quirks, Unfair is a winner with its beautiful deck, fun game play, and massive replay ability.

Pros

- Theme is perfectly applied

- Card art is wonderful

- Great replay value

- Park building mechanics work smoothly

Cons

- Coins too powerful in victory check

- Excessive dirty play can bog game down

- Friendly play can limit strategy