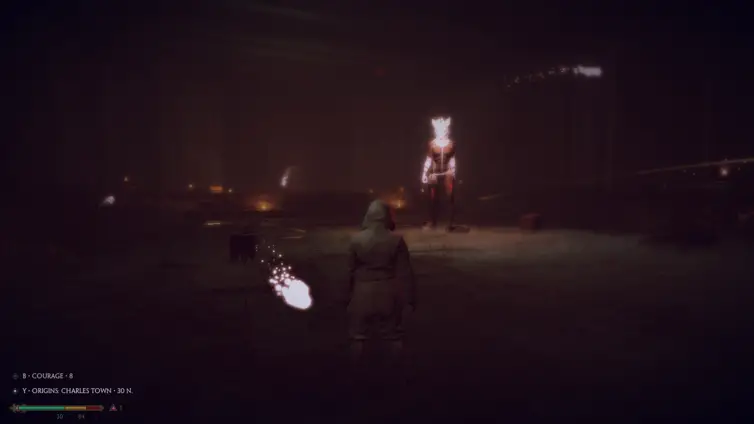

So there I was, using the power of my hometown to fight an enormous woman in a bikini with the head of an eagle and candles burning on top of her, when my old, dead, family dog shows up to help me… you know what? Let me back up a little bit.

I booted up Jason Oda’s Waking and was greeted with a unique disclaimer: “WAKING explores sensitive personal themes and allows you to dive into your memories, feelings, and emotions. If you have a history of depression, anxiety, or self-harm, the game may not be suitable for you. Please make the decision based on your understanding of your mental health.” It was clear even before the start menu that I was in for something tough to digest. Reviewing video games that you’ve never played before is a strange way to experience art. It isn’t like a movie where the runtime is finite; if you are locked into a stressful situation in a video game, you can’t know for sure when it is going to be over. You can close your eyes during a frightening part of a horror movie, but in a video game, closing your eyes only delays the inevitable. Instead of watching someone braver than you struggle, you are in charge of your own relief. And that is exactly what Waking is all about.

The first scene in the game shows you a coma patient lying in a hospital bed, covered head to toe in bandages. The patient is you. Not Master Chief, not Captain Price, or some other fantastical hero, it is you. Since your body is broken and cannot move, the character you control throughout the game is a dark, cloaked figure. Is this you in another world? Your soul? Death, or life, manifested? A mysterious voice speaks to you, calling you by name, in a language you can’t understand, so subtitles translate it for you. It asks you if you can feel your life slipping away and then it gives you a broad objective: to make peace with it and “go into the light.” It is unclear if the entire experience of this game is actually happening to you, or if it’s only happening in your thoughts and dreams, or if it should all simply be seen as one huge metaphor for death. Waking loves to ask you big, ambiguous questions and not answer them because it knows its themes are thought-provoking enough that you become eager to answer them for yourself. Because everyone thinks of life, death, and the afterlife differently, each player will have different experiences throughout.

The story of Waking seemed to begin with me setting out on a mission to accept death and ease my own passing. Not far into the game, I was asked whether I was ready to die or whether I wanted to keep on living. I answered that I wanted to live, and from then on, my missions consisted of me fighting off agents of death, hellbent on keeping me from ever waking up because they see the struggle for life as a weakness; an immaturity. Sometimes the objectives were physical representations of healthy mental exercises, like fighting off your “personal demon,” or “confronting your pain and suffering,” while other missions consisted of the literal repairing of a dying human body, like repairing a neural bridge, or revitalizing nerve receptors. The teleporters that move you between areas are axons: nerve extensions that transmit electrical impulses. To someone who knows next to nothing about mental health and human brain anatomy, each mission really did feel vital because I didn’t fully understand what I was risking, so I found myself trying hard and being careful, terrified to make mistakes inside my own head.

The main enemies you encounter in Waking are called Death Counselors. These are the beings whose objective is to coax you into death instead of allowing you to heal yourself and wake. They tend to have human-shaped bodies, sometimes with colorful, tribal-like skin markings, and they often have animal heads, or sometimes human heads with animal-like features, like antlers. Early in the game, some of these creatures can be seen building machines that will become another class of enemy standing in your way: Sleepkeepers. Sleepkeepers look like hovering orbs made of sharp blades and they attack you with bullets made of light. There are also smaller enemies that look similar to Sleepkeepers, and a collection of mini-bosses that often look like a bigger, or scarier version of one of the base enemy models. Some mechanical enemies are color-coded to identify what their special strength is, like movement speed or quicker attacks. You have a fear meter which increases as you take hits, and the fear level determines the strength of some enemies’ shields.

The maps of the game are meant to be ambiguously beautiful. They are randomly generated, which sounded interesting, and they are often colorful. Glowing orange fields of grass, misty red forests, dark watery caves, and so on. They perfectly match the tone of the game. It did, however, actually take me a while to realize that the layouts of the maps were randomly generated because they are all so fluid and they don’t necessarily conform to the rules of real-life biomes anyway. If you die and have to restart, a portal might be in a different place than before, or an enemy might be sitting to your left instead of to your right and so on, but it often didn’t make too much of a difference.

Your safehouse in the game is a palace. One room in the palace is your hospital room, but the rest of the place has medieval-looking rooms and the hallways, made with epic stone walls, that fill up with the memories you amass as you progress in the game. At any point during gameplay, you can return to the palace and restart a level by choosing it on the progress map, which is called the “Mindscape,” or you can go through a tutorial again, or just browse through the memories you’ve collected so far. The mindscape is meant to show your path and guide you in the right direction. Portals that lead to missions in the main questline are marked as such, but not always. I occasionally found myself having to fight through what I’d thought was a side mission in order to move on.

The character’s movement is controlled by the classic setup of left stick moves you, right stick moves the camera. The combat mechanics are also quite simple, inviting satisfying attack and defense moves with a low skill ceiling rather than difficult, precise, competitive combat. The main ability available to you is telekinesis. You can pick up an item, like a piece of clutter that scatters the grounds of your insides, charge it in your hand, and throw it at enemies, which often drop different power ups when they’re hit. Your aim locks on to enemies just by holding a button, which makes aiming easy, but can be annoying when fighting more than one enemy. Most enemies need to be stunned by thrown objects before they can be meleed for damage points. Melee attacks are fueled by your feelings, which are manifested as pyramid-shaped drops, so unlike most games, it is possible to run out of the ability to hit things entirely, which frustrated me sometimes. I would simply rather run up and strike something than have to run around looking for a bucket to throw at my target. Also, some melee attacks double as projectile attacks, which left me kind of confused. One way to deal damage to an enemy that shoots missiles of some kind is to pick up and charge a shield, which reflects enemy attacks back at it, and they hardly ever miss, which I quickly discovered makes shields overpowered to an extent. If you find yourself in need of attacking an enemy, but lack the needed weapon charges, you can spend a mana-like currency, neurons, to use a “memory” which does a few different things depending on what the memory is, often spawning a shield, melee credits, projectiles, etc. There are extensive tutorials at the beginning of the game, so although everything feels strange at first, it is easy to get a hang of it with a little effort.

The various attacks available to you give the game an opportunity to apply some unique customization options. At certain times in the game, you see an image of what looks like an angel standing over your hospital bed. You are asked to close your eyes and you go through a couple minutes of meditating as the game makes you reminisce about an old friend, or your old neighborhood, and so on. Or sometimes, you are stopped and asked by that same mysterious voice from before about yourself. The questions range from personal questions about your mental past like, what ambitions did you have, or what vices did you struggle with, to questions about where you grew up, who you had a crush on when you were younger, and so on. The answers you provide become physical powers that you use to attack enemies. If you say that you are from Chicago, you may be given the power to spawn useful items by using the power of Chicago. If you say that in your past, you struggled with addiction, you may be given the ability to equip “addiction,” and melee enemies with the power of those feelings. The game also tugs on your heart strings at times by giving you the power to spawn a follower/sidekick, in the form of an old pet that has died, or the memory of a best friend of yours from kindergarten. Most of the answers you give the game are typed manually by you, so the game even refers to them by name. The developers clearly appreciated the fact that gamers come from all kinds of backgrounds and attempted to give as much of a blank slate as possible so that every minute of the game feels personal, emotional, and meaningful.

Waking can sometimes feel repetitive, but it certainly never feels tedious. There are never huge amounts of small, weak enemies that you have to blast one by one, but at times I felt like I was just entering a dungeon, clearing it of Sleepkeepers, and repeating. The progress you make repairing your body does feel satisfying, but the methods of doing so often look way too similar.

While progressing, the game autosaves when objectives are beaten, but this doesn’t happen often enough. Sometimes, I found myself having to re-do about 30-40 minutes worth of work because I died near the end of a task. The game is partially open world, and since it consists of main quests, side quests, mini health missions, and mazes, it would be nice to be able to save wherever you’re standing. Otherwise, if you get a phone call, or you have to go out, etc., you’re forced to make a decision between finishing a mission before leaving, or quitting, and sometimes it felt like significant progress was lost.