If you haven’t played Dune: Imperium, you probably should: 100/100. /end_review

Wait, wait – before you go off to buy Dune: Imperium, the story is a little more complicated than a one line summary. Yes, I think it’s 100/100. Yes, I think you should probably play it – but you might want to play it before buying it, or at least read the rest of this review first. Dune: Imperium is either revolutionary or majorly evolutionary (depending on your point of view) – and is an amazing experience. However, it has some potential flaws.

Released in 2020, Dune: Imperium was one of two games to attempt to create a hybrid deck building and worker game in 2020. Both it and Lost Ruins of Anark, the other hybrid, are successes that are undoubtedly worth your time. However, in my opinion, Dune: Imperium is better, does more, and is slightly cheaper. Perhaps this should be unsurprising as Dune: Imperium has the benefit of pedigree: Dune: Imperium is designed by Paul Dennen and published by Dire Wolf Digital – both of which are responsible for the very successful Clank! series of games, which is another deck building hybrid (nominally deck builder + dungeon crawler).

In Dune: Imperium, you play as one of the major figures from one of the major houses in the Dune franchise. Similar to many modern games, you are trying to accrue more victory points (VP) than your competitors. The game ends after 10 rounds or after anyone achieves 10 VP. (VP can go over 10, but gaining 10 is a trigger for the end of the game.) VP can be earned in a lot of different ways: by winning some conflicts, by currying favor with the 4 different factions, by the effects of Intrigue cards, and by buying player cards or using player card effects. Even with so many ways to gain VP, actually getting VP is hard and the scoring is often very tight. Out of dozens of non-solo plays, the largest score gap I’ve had was only 3 VP between the winner and the lowest scoring player.

When the game begins, everyone has a 10 card deck, 2 agents (workers), 1 water resource, and a unique leader with a special starting power and an additional special ability that can be triggered whenever their player plays a card with the Signet Ring icon. Unfortunately, not all the leaders are created equally. While asymmetric powers can always potentially be unbalanced in certain situations, with certain play styles, and with more or less experience; “The Beast” Rabban stands out as a particularly poorly balanced leader. His unique bonus is a one-time gain of 1 spice and 1 solari at the start of the game, which can lead to strong starts; but the route to that strong start is also very narrow and specific. He is thus potentially easily (and even unintentionally) blocked or derailed, particularly at 4 players and/or if Rabban goes later in the player order. If this start is blocked, derailed, or otherwise delayed; Rabban’s one-time starting advantage can be largely nullified. Meanwhile, the other leaders generally have ongoing effects that will potentially be useful throughout the game or (in two cases) really potent 1 time effects.

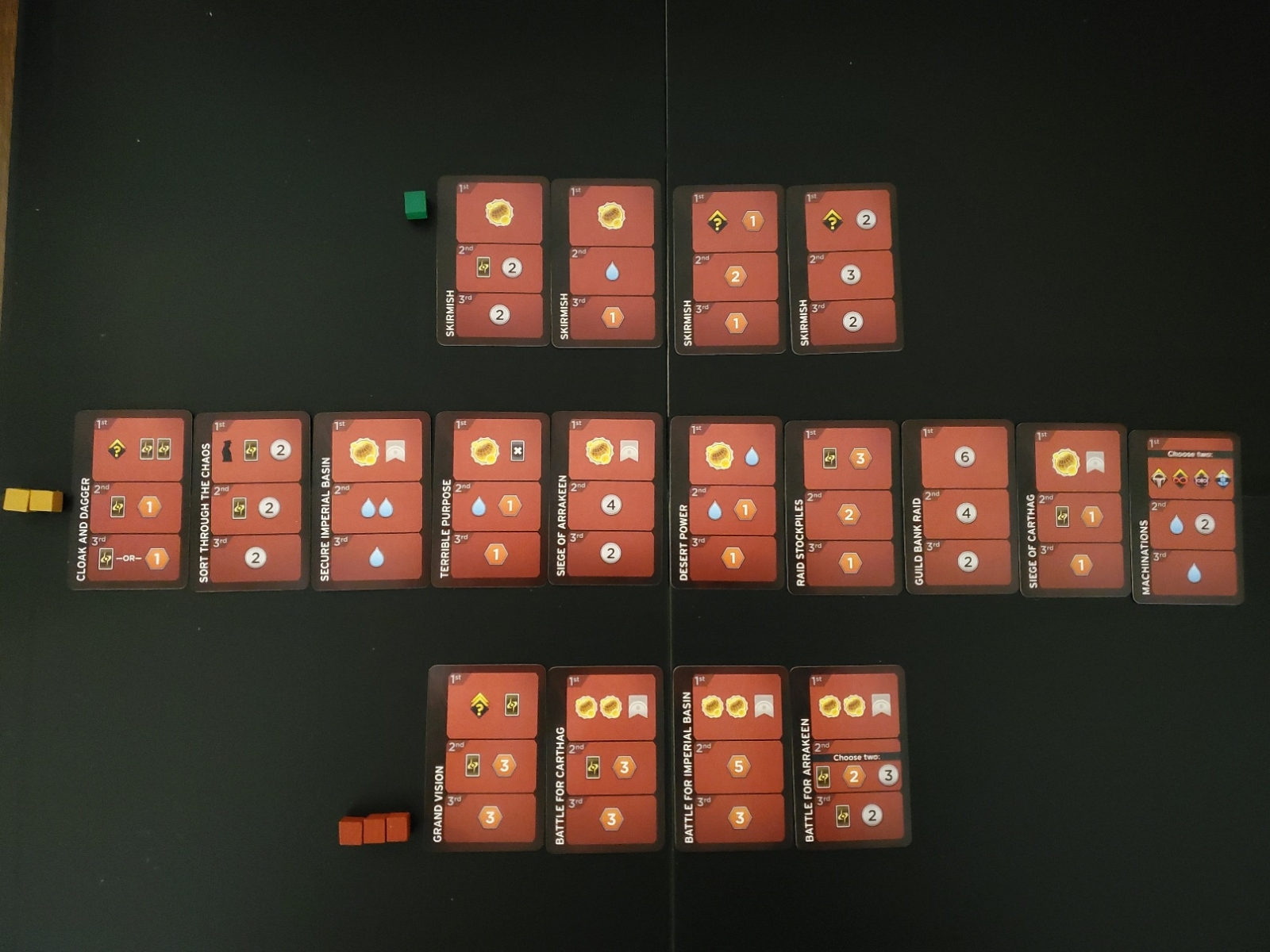

At the start of each round, a new conflict card is revealed and players draw a hand of 5 cards. Afterwards, players take turns taking either agent or reveal turns until every player has taken a reveal turn. If a player has no unplaced agents, they can’t take any more agent turns and must take a reveal turn. However, a player may take a reveal turn even if they still have unplaced agents. Once a player has taken a reveal turn, they cannot take any more turns that round. Cards played during a round remain in play and do not go into the discard pile until the end of the reveal turn.

When a player chooses to take an agent turn, they play a card from their hand and place one of their unplaced agents at a location that matches one of the symbols on the card played so long as they can also meet any additional requirements for placing at that space (such as having to pay money/solari, spice, or water – or requiring a certain level of faction standing). If there are any effects in the grey box near the bottom of the card, the player can resolve those effects and the effects of the space the player landed on in any order.

On a reveal turn, the player reveals the cards remaining in their hand, resolves any effects in the blue box at the bottom of the card, calculates their combat score in the conflict, and buys any cards they want from those available to add to their deck via their discard pile. Players may also have additional persuasion from Landsraad spaces that may be used to purchase cards. When purchased, some cards will have symbols next to their cost which indicate the card gives an immediate benefit – such as VP, influence, or resources. Cards purchased from the Imperial (market) row are immediately replaced.

Once all players have had their reveal turn, the combat phase of the game begins. In turn order, players may choose to play Intrigue cards that could influence the outcome of the battle, or pass. Once all players have passed consecutively, the final combat scores are totaled and rewards are given out. For example in a 1-3 player game, only first and second place rewards are given out. Ties for a place give out the reward for the next lowest place, resulting in ties for 3rd place giving nothing.

For combat, troop resources are worth 2 combat points each and combat symbols from cards in hand (or intrigue cards) are worth 1 combat point each. As a player’s combat strength is calculated on their reveal turn and all troops committed to a conflict are lost when it is resolved, it can be useful to try and delay a reveal turn: the person who goes later (such as by being later in the turn order, or using the Mentat) will have more information about the strength of forces in the conflict at the cost of potentially not being able to go to board spaces they might have wanted to go to.

At the end of the round, any spice harvesting spaces that don’t have agents on them gain a bonus spice, making them more valuable to visit on future turns. Then the Mentat and agents are removed from the board: agents are returned to their owners and the Mentat is returned to its board location.

In my experience, spice is a hot commodity in 4 player games, particularly early and late in game, and spice harvesting spaces don’t tend to accumulate a ton of extra spice. Spice is one of the fastest ways to gain money to purchase a player’s Swordmaster (3rd agent/worker) and/or High Council Seat (permanent +2 persuasion to buy cards every round). Spice is also a resource needed to visit some of the best board spaces, and often fuels powerful card effects. In the endgame, spice is the first tiebreaker and, as the Dune: Imperium is a fairly low scoring game, VP ties are not infrequent. All of this puts a lot of pressure on collecting spice in a 4 player game. Conversely, spice harvesting spaces in 1-3 player games can regularly accumulate bonus spice – sometimes to mouth watering degrees.

I’ve probably buried the lede here in between rules discussion above and deeper dives into various elements below, but the magic sauce in Dune: Imperium is trying to figure out what to do on any given turn. There are a lot of random elements you have to try and account for, and decisions to make: what is in the Imperial/market row that you (or others) can buy? What cards will you draw that may allow you to go where or do what? Do you spend those cards to go to locations or do you keep them for your reveal? Do you go to a location that has something you want/need? or do you go to a location you don’t want to go to as much because you have an agent turn card effect and that card only allows you to go to two places? or do you go to a location to block another player from going to that location as you know they could take away your influence lead or would be able to flood the current conflict with troops and make you lose? or do you take an early reveal turn because you really need the persuasion or combat values on the bottom of the card to buy cards or help in the conflict – or you really want to use a reveal effect to gain resources like spice or solari? And what cards are in other people’s decks? Based on what’s in their discard pile, what is in their hands? Based off the board state and what’s possibly in their hands, where might they go or what might they do? Do you need to go to that space first, or can it wait? Can harvesting that spice wait until the next round when there could be a bonus spice, or is someone going to swoop in and take it this turn? What’s the reward for winning the conflict this round? What’s the reward for second (or even third) place? Who all might be invested? Is it worth sending out just a troop to scoop up whatever might be at the bottom? Do you want to try and delay and see what people commit to see if the conflict will be worth it? How much can people afford to potentially dedicate to the conflict? Do you go in heavy up front to try and deter people from bothering? or do you make a modest front? or do you skip the conflict altogether because you don’t think the rewards are worth it or because you don’t think you’ll be able to win?

That’s the beauty of Dune: Imperium. There are a lot of interworking systems to be aware of and keep track of, and a lot of decisions to evaluate based on a lot of probability crunching – and it’s not in a vacuum. Unlike a lot of Euros, especially worker placement games, I feel very connected to other players in Dune: Imperium. There’s a lot of things people can do every turn that impact what I want to do. Other players can do more than just block the space I want to go to, they can also buy the cards I want for my deck, steal my lead on the influence tracks, and beat me in the conflict.

Some other concepts that deserve to be talked about:

Intrigue Cards

This game has a deck of intrigue cards that can influence the game. Various spaces and cards can potentially allow you to blindly draw them from a randomly shuffled deck and they can potentially be stolen by players using the Bene Gesserit space “Secrets”. The 40 Intrigue cards are kept secret until used and come in three varieties: 26 plot cards, 11 combat cards, 2 endgame cards, and 1 card that is both a combat and endgame card. Endgame cards are only revealed at the end of the game.

The two dedicated endgame cards grant bonus VP if you fulfill certain requirements, while the half combat/half endgame card “Tiebreaker” grants +10 spice if used for it’s endgame half. Total spice is the first tiebreaker if two players are tied for VP when the game ends, and spice tends to be a very useful resource during the game – so +10 spice can very much break a tie in the favor of the person playing “Tiebreaker”.

The combat Intrigue cards generally add combat value, but can allow for other combat actions, such as being able to hastily retreat forces from a conflict, or granting spice, influence, or even a VP based on the outcome of the battle. Retreating forces can be invaluable if a player finds themselves committed to a conflict they now know they are going to lose – or as an intentional feint to get other players to overcommit to the current conflict leaving them exhausted for the next turn’s conflict.

As the last 4 conflict cards are always the same (albeit in a variable order) and 3 out of 4 of them contain 2 VP, it can be very useful to draw other players heavily into a round 6 conflict – and withdraw to sap their reserves while maintaining your own. The hope here being the 75% chance of having more resources going into a 2 VP conflict. (The first six conflict cards are randomly selected from two larger pools of conflict cards, so what conflicts may occur in the first six rounds is fairly unknown.)

The last set of Intrigue cards are plot cards, and they can have a whole host of different effects far too numerous to list here. However, they can have huge impacts on the game state – such as allowing the conversion of resources into VP, suddenly and unexpectedly gaining influence, or being able to visit spaces you wouldn’t normally be able to visit. On the other hand, several are very situational, and therefore potentially useless.

Take “Charisma” as an example. It grants +2 persuasion during one reveal turn, and it can be a game changer if it allows you to (unexpectedly to other players) buy a card that grants immediate VP (and maybe trigger the end of the game), or buy a really great card other players wouldn’t have expected you to be able to buy and maybe had planned their turns around buying themselves. However, “Charisma” could be useless if you are never 2 persuasion short of buying anything you want all game long.

Influence Tracks

There are 4 different Influence Tracks, each 7 spaces long and representing one of the non-House powers involved in the fate of Arrakis: The Emperor, the Spacing Guild, the Bene Gesserit, and the Fremen. Advancing along these tracks is a great way to get VP, especially in such a low scoring game. No matter what any other player does, every player who reaches the second influence spot in each track gets 1 VP. That’s 4 VP (out of 10!) for a fairly small investment, as Influence can be gained through card and Intrigue card effects or by going to the relevant faction’s board spaces, which themselves give out a number of bonuses in addition to influence with that faction.

Beyond that, faction tracks give out a faction-specific reward every time you move up into the 4th faction influence space. (As some card effects allow you to move down on faction tracks, you can potentially set up a situation where you move back and forth between the 3rd and 4th space, and gain the faction reward multiple times.) The first person to reach the 4th space also gains an alliance with that faction. Faction alliances grant 1 VP for as long as they hold that alliance, and having an alliance may allow triggering certain card or leader effects.

Any player who moves to a higher space on the faction influence track than the current alliance holder gains the alliance from the current alliance older. (If a player is at the top/seventh space on the influence track, they can’t be passed and the alliance cannot be taken from them without them moving lower on the influence track first.) The fact that players can be passed on the tracks can lead to some major upsets/swings in VP scoring, particularly given how tight the game is. Gaining an alliance will gain a player 1 VP, but the person losing that alliance will lose 1 VP. A shift of 2 VP in a 10 VP game is huge (1/5th of the VP needed to trigger the end game).

Some of the most tense and ultimately enjoyable (if frustrating in the moment) games of Dune: Imperium I have played have been where I’ve had to choose between being involved in a round conflict where VP was at stake or moving up one or more influence tracks for factions in which I held the alliance because one or more players are on the same track space as I am. There’s a lot of tension there as a conflict may win you 1 VP (or 2 VP late game), but losing one (or, worse, two) alliances will not only cost you VP, but grant VP to your rival. Guessing wrong can be enough to swing you from potentially winning that turn to handing a win to an opponent. Absolutely delicious.

Deck Building

Even more so than normal deck builders, what goes into your deck is important. There isn’t a lot of space for “junk”. At best, the game will last 10 rounds, and you draw a default of 5 cards every round. Your initial deck is composed of 10 cards, with one card that will auto trash upon use to place an agent. That gives you one card you can add to stay at a 10 card deck. If you have a 10 card deck, at best, without draw effects, you will cycle your deck 5 times.

If you are playing a 4 player game, 10 rounds isn’t uncommon – but I’ve generally found that 3 player and fewer games routinely end before round 10, leading to even fewer chances for your deck to cycle. If you are familiar with deck builders, you might think you can power through this via draw and trash effects. You are kinda correct, but also potentially setting yourself up for a bad game experience.

Drawing combos are harder than in many deck builders. In Dune: Imperium, cards can’t be directly played to draw cards. Cards and spaces that allow drawing typically are triggered by playing one of your agents/workers, which are very limited, since you start with just 2 agents, with the potential to buy only one more (your Swordmaster). Additionally, placing an agent requires placing a card with specific symbols (and potentially expending resources). This makes card draw a very expensive proposition. This is not to say card draw isn’t necessarily worth it – it will depend on your circumstances and deck.

However, card draw in Dune: Imperium isn’t anywhere near as powerful as it is in many other deck builders because of the overhead cost to play cards or going to spaces that allow for card draw. In many deck builders, the cost of drawing a card is generally just playing a card that draws and, thus, even having a card that allows you to just draw one card by playing one card doesn’t tend to hurt your deck, as such cards don’t tend to limit your total actions. If you have spare purchase power, you won’t generally hurt yourself in many deck builders by picking up a play one/draw one card. It will quickly cycle itself.

Yet, in Dune: Imperium, you need to potentially give up one of your limited agents to draw cards. Even with a very aggressive second turn to gain a Swordmaster, you are looking at maybe 29 agent placements. If you are playing a game that lasts, say, 8 rounds and you don’t manage to get a Swordmaster until round 4, you are looking at maybe only 21 agent placements. If you are skipping getting a Swordmaster at all, you are looking at maybe only 20 agent placements for a game that runs 10 rounds, or just maybe 16 agent placements for a game that lasts 8 rounds.

Deck thinning is rare and expensive too – and, given how short the game is, the utility of deck thinning drops pretty sharply as the game progresses. With tight deck construction and a long game, you might only cycle through your deck 5 times. There are only 7 (out of the 67) market purchasable player cards that allow trashing other cards. As the cards are drawn for the market at random, you may never see them in an entire game – and, if they show up in the latter half of the game, they might not be worth the effort. Like with card draw, card thinning tends to be tied to agent placement effects, so you won’t be able to combo it nigh infinitely like you might with other deck building games.

The only reliable method of trashing cards from your deck is the Bene Gesserit space “Selective Breeding,” which allows you to trash a card and draw two more cards. However, it is only available to one player once a round (so a max of 10 total uses in a 10 round game), and it costs not only an agent placement and a card from your hand but also 2 spice – which is valuable for a ton of other uses as well.

All this leads to what I said above, you need to build your deck very carefully. If there is nothing in the market that will clearly improve your deck (especially if you aren’t lucky enough to have been able to purchase a deck thinning card to avoid deck dilution), your best option is to pass. If there’s nothing in the market that will clearly improve anyone’s deck, the market can even get “stuck”. While markets getting stuck is a problem in a number of deck builders, it can be even worse in Dune: Imperium, given how tight the deck construction is.

I don’t think this deck building is bad per say. I think it works as intended – as one element of the entire game. Dune: Imperium isn’t a deck builder or a worker placement game (or, by any means, a war game). While Dune: Imperium does blend a lot of different elements and mechanics together, they are all just tools to be used in game as opposed to being the game itself. In one game, deck building might not be particularly useful. In another, following a conflict-heavy strategy might not be useful (as the first 6 conflicts could all be “junk”). Workers might be a lot less useful if you do manage to have a series of good, early market draws and purchases that allow an efficient VP engine. Dune: Imperium is a game that rewards flexibility and adaptability to changing conditions over rigidly solving for an optimal puzzle solution – and this can mean abandoning certain aspects of the game.

And that leads us to…

The Landsraad

While the Landsraad takes up 1/3rd of the non-faction/influence composition of the board, it’s also the most situationally useful, and is often useless most rounds. Both the High Council and Swordmaster spaces are expensive and one-time use, and you generally will only want to gain one of them in any given game. While it is possible to try to pursue both strategies centered around placing workers or building a deck focused on making card purchases, you are generally going to do better by picking one or the other: placing agents eats into the cards you have available to buy more cards with. Also, the choice for going for VP through deck building is going to be highly dependent on what is actually out in the market row in the first round or two of the game, as that’s when you’d be securing and getting the most mileage out of the cards key to such a VP purchasing engine.

The Hall of the Oratory is probably the worst way to gain 1 troop. It is only really worth visiting if you absolutely know you only need 1 persuasion to buy a card during your reveal turn and you absolutely know no one will or can take it before you. (It’s not really a good option almost ever.)

The Mentat is great for helping you delay – if you need to delay for some reason. It grants you a card draw and the ability to place the Mentat once like you would an agent for the cost of 2 solari. As you still have an agent and you draw a card, you basically pay 2 solari to delay a turn until later in the round. Exception: Leto and Ilban can get more mileage out of this. Leto’s cost is reduced to 1 solari (which can be a significant impact depending on your strategy and situation) and Ilban gets to draw an additional card – which, given how resource intensive card draw can be, can be a huge boon (depending on your strategy).

Lastly, Rally Troops is generally (though not always) one of the worst ways (aside from Hall of the Oratory) to get troops when you need them. Not only does it cost 4 solari (which will generally take at least two actions to secure), it doesn’t allow you to deploy any troops directly into the conflict; and combat spaces, marked by crossed swords/knives on the map, only allow you to move up to two troops from your garrison into the conflict. In order to get all 4 of those troops into a current round conflict, you’ll need to follow up with two agent moves to combat spaces – which means you probably aren’t generating the solari for the troops, visiting Rally Troops, and deploying troops in the same phase. Much like Mentat, Leto and Ilban can use this space more effectively – especially as Leto can always get enough solari to use this just by going to one space – Secure Contract. Rally Troops is really a “long(er)” term planning space – and Dune: Imperium, particularly when it comes to conflicts, rewards flexibility and opportunism.

Solari, while critical for getting a Swordmaster and/or High Council seat, isn’t as useful and flexible as spice. You are probably less likely to have solari on hand than spice (or water), which makes Rally Troops ironically often less accessible and useful than the amazing Heighliner or even Conspire spaces. For reference, Heighliner costs 6 spice but grants 1 influence with the Spacing Guild, 5 troops that can go right into the conflict, allows you to move 2 troops from your garrison into the conflict, and grants 2 water. That 2 water can then (potentially) be used to gain more spice (say by visiting the Great Flat for 3+ spice) or the Fremen’s Hard Warriors (for 2 more troops and 1 Fremen influence). Troops are arguably the least flexible/fungible resource, as they are only good in conflicts and, if stored in the garrison, can only trickle out.

House Hagal (the 1 and 2 player modes)

To be frank, I think Dune: Imperium shines at 4 players. It feels tighter and way more cutthroat, even if the game tends to run longer. A number of people I know prefer it at 3, but I don’t think there’s as much conflict there. And that gets us to the 1 and 2 player modes. They’re alright in my opinion.

Automated (non-electronic) opponents designed to work in a competitive board game almost never work in my experience. Automated board game opponents often work well in games designed to be solo or co-op. However, in competitive games, they are almost always lacking, and, if I’m going to play them solo, I’d almost always prefer to just play multi-handed against myself. Dune: Imperium is no exception.

In solo play, you play against two opponents driven by the House Hagal cards – and the opponents aren’t particularly good. Like many automated opponents for competitive games, the quality of their actions was all over the map. I had a couple of games where one of the two opponents would threaten me for a VP win. However, more often, one (or both) opponents would take actions that weren’t optimal for the board state – whether to improve their position or to hurt mine. They’d just kinda meander around the board unintelligently and gain a rather pitiful amount of VP.

In two player play, there isn’t really an automated opponent. Instead, the “third player” is more of just a spoiler force randomly moving to spaces and denying access to places and resources. While I think this works, particularly in comparison to solo play, as the automated faction isn’t really an opponent; I think it’s still inferior to playing at higher player counts. Play at less than 4 players is comparatively laid back, and randomly having access denied to spaces you might have been counting on is frustrating. When humans are making decisions, where they place is normally going to make sense based on what they want or need and have access to, so you can reasonably try to figure out what spaces might be used by people going before you by paying attention to the board state including how other people are building their decks and what cards are still in their discard piles. To me, that’s where a lot of fun of a lot of games comes from, and you can’t really predict the automated spoiler here.

Dune: Imperium Integration App

If you are so inclined, Dire Wolf Digital does provide app support for Dune: Imperium. Overall, it’s ok. If you play solo or two player, it’s an improvement: the digital iteration of House Hagal will now occasionally churn the Imperial/market row – which, as you might expect, is a huge improvement for both game modes. You are less likely to get stuck with a market row full of nothing you want, especially in 1 player.

There are also two additional game modes for 3-4 players: “Arrakeen Scouts” and “Blitz!”. “Arrakeen Scouts” is ok. It adds missions and events every round, and one-time variable subcommittee bonuses. I don’t know that Dune: Imperium needs it. There are already a lot of different variables and random elements to try and keep track of/predict/account for, and the missions and events of the app feel more opaque than the physical components. With decks, I can physically look at them and theoretically learn everything that’s in them. I can then reasonably guess at probabilities – which I can’t really do with the app. I have no idea how many events there are or if new ones could be added or removed at any time. I also can’t manually customize the experience at my table if I wanted to, like I would be able to do with a deck of physical cards. While I prefer the game without this mode; some people I have played with have really, really enjoyed them. Your mileage may vary.

I don’t care for “Blitz!”. The game is already reasonably short in my opinion, and “Blitz!” makes it even shorter. It also basically strips out the deck building for an upfront draft, and mucks around with how the influence track competitions work via its political schemes. Everyone suddenly gaining 3 influence on round 3 is a huge disruption – even if they had to decide on where it was going on round 1. The only really interesting addition is the Shadow Backer. This feature is somewhat similar to the Bene Gesserit’s ability to predict the winner in the original Dune (1979/2019) game. At the beginning of the game, they take a guess at who they think will win the game before taking into account Shadow Backer VP. Players cannot choose themselves. If they are the only player that guesses correctly, they gain 2 VP. If multiple players guess right, they all get 1 VP. If a new player would win based on the new VP score and any tiebreakers, they win. I do like this quite a bit, and kinda wish it was in the base game.

The app already seems updated for compatibility with the upcoming expansion Rise of Ix. I would love to have tried it out. Unfortunately, I don’t have access to a copy of Rise of Ix yet. If you are reading this Dire Wolf Digital, I am in Colorado…

Theme

Dune: Imperium isn’t particularly thematic – at least not in the sense I view thematic games. I do think it’s way more thematic than most Euros and Euro adjacent games – but that’s not saying much. Many Euros can be easily reskinned to fit any theme. To me, thematic games have mechanics that really reflect the source material or concepts that the game is trying to invoke. While you can sometimes separate out the rules from the theme and reskin a thematic game for a different theme, the reskinned game is probably going to suffer and be a significantly lesser experience.

Dune: Imperium doesn’t conflict with the notion of being the ruler of a galactic noble house in the Dune universe, but its mechanics don’t feel tied and bound to that experience. I feel like this game could easily be reskinned for another, non-Dune theme pretty easily. Then again, Dire Wolf Digital has some stiff competition when it comes to the Dune thematic space, and that might tint my view of it a bit. While it’s not for everyone, I feel Dune (1979/2019) is one of the most thematic board games you can play, and most certainly the most thematic Dune board game you can play. However, Dune (1979/2019) is also a lot longer, a lot more complex, basically only plays 6 people, and is (mechanically) in an entirely different game genre from Dune: Imperium.

Components

The components of the base/original game are excellent. The board is beautiful. The card art is beautiful. There are no movie stills, which are generally horrible in games, but the art still invokes the feel of the films – which is the best of both worlds. There is nothing wrong with the cardboard and wooden tokens that come with the game: they are all solid and usable. The wooden resources in particular have a nice solid feel and stand out both due to shape and color from one another and the board itself. The only negative is the box: it’s beautiful, but it is also huge and has a mostly useless four-equal-section internal divider. Note: The box is beautiful enough though that I might repurpose it for my copy of Dune (2019).

That said, I have the upgraded edition/components. That’s why you see all my cards in sleeves – they came with the upgrade. I don’t know that I’d recommend it for anyone who hasn’t played the game yet, unless you are a fan of Dune, but I am enjoying it. However, it was a birthday gift from my partner, and I’m somewhat of a fan of Dune – I’m pretty sure I would have enjoyed the minis and the surprisingly heavy metal 1st player coin even if I hadn’t liked the game.

While the upgrade box is twice the size of the normal box, the internal storage is built to fit everything really well. I hope it will fit Rise of Ix as well: it would be a shame if it doesn’t. The sleeves are… sleeves. The art is nice, as is the silvery inside backing – but they are still just sleeves. It does feel a bit odd that there are no sleeves for the smaller Conflict and Intrigue cards and not enough sleeves with the upgraded edition for the House Hagal cards. The Conflict and Intrigue cards don’t get shuffled much and you can (for now) use the app in place of the House Hagal cards, so the lack of sleeves for these is not huge. It’s just odd.

The minis are really nice, though the troops do line up with certain houses’ film incarnations. Red is clearly Harkonnen and green are clearly (armored) Atreides, which can lead to some weird situations in game – as can the fact that player agents are clearly divided along faction lines with 3 Sardaukar (Emperor), 3 Space Guild administrators (Space Guild), 3 Bene Gesserit sisters (Bene Gesserit), and 3 Fedaykin (Fremen). (Included in the upgrade are four different colored sets of 3 base rings so that you can tell to which player each agent belongs). Then again, immersion for fans was kinda broken long before that in the base game – what with being able to have Paul facing off against his dad Leto.

The Conflict

I’m adding this as a specific callout as a number of people I know were concerned about the amount of conflict in the game before playing, and I suspect many other people might be as well. Yes, Dune: Imperium has more conflict in it than many Euros. The worker placement is on the more aggressive side, and there is an event every round called the “Conflict”.

However, the conflict is more like a bidding or race system than the combat one might find in a traditional war or area control game. There is one conflict space. You either spend resources (troops) or you don’t. You can play some cards afterwards to modify the value of the resources you put in, and then everyone compares what everyone’s total value was. Rewards are given out based on whose values were higher than others. All spent resources and Intrigue cards are lost. It’s definitely a conflict, it uses combat related terms like combat and troops and conflict, and it definitely drives some people’s actions each round depending on what the reward is – but it’s not really anything resembling combat in virtually any combat-based game. It’s more like an once a round open all-pay auction, where you have to commit to spending your bid amount regardless of whether or not you win the auction.

I think the Conflict system is great, and really works as a part of Dune: Imperium. It gives the game a constantly shifting focus and priority, particularly with all the different rewards that pop up in the early game. It also gives one more area on which to vie for player attention. This entire section, though, is here to help set expectations, not pass negative judgment.

In closing…

I struggled as to what score to give Dune: Imperium. No individual mechanic in this game is unique and it is not a flawless game – with some of those flaws potentially being make-or-break-it issues for some people. However, Dune: Imperium is a novel combination of game mechanics that could give rise to an entire genre of games, and it is a great experience that I not only still enjoy but am eager to revisit even after dozens of plays. The latter is not something I can easily say about most new games I play. Maybe in the future I’ll change my mind; but, after one year with Dune: Imperium, I’m going to rate it 100/100 on the Gaming Trend rating scale.