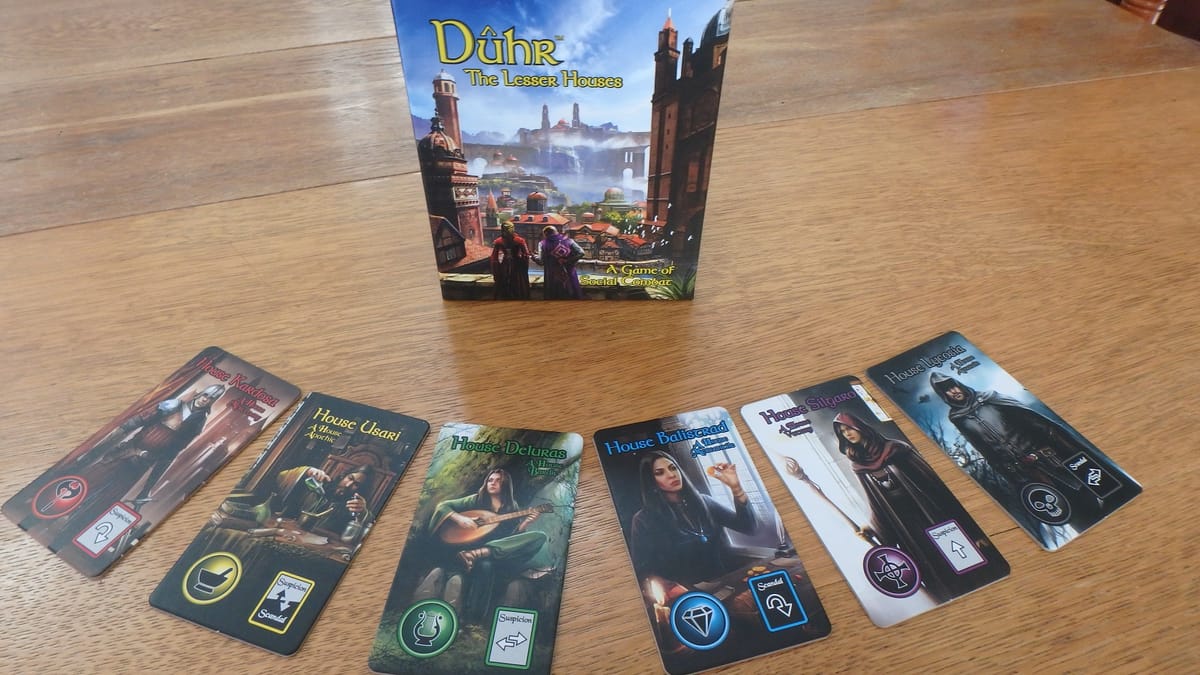

Duhr is, without a doubt, one of the strangest games in my collection. In the modern era where it seems like every game is fighting to get on “games everyone should have in their collection” lists, it unapologetically only works for a niche audience. While most publishers will size a game’s box to its gameplay depth/length regardless of the space that the components need, Duhr is in one of the most compact boxes in my collection. And while Kickstarter games reap in cash by adding unnecessary deluxe components and expansions, this box almost feels threadbare- the cards are tiny, and the only art is on player houses. All of this culminates in a game that I have honestly never had a good session with, but will simultaneously never leave my collection.

But it’s not just Duhr’s box and components that are deceptively minimalist; its rules are also simple in a way that doesn’t really jive with a game this complex. Setup is snappy- each player is randomly given a house with an asymmetric power, two secret agendas to choose from (endgame bonus objectives), a house’s hidden conspiracy, and a hand of suspicion and scandal cards. Player turns are equally straightforward- on their turn, a player simply plays a card from their hand. Suspicion cards are house-aligned, and can either be played on an opposing house by another player to give them a negative point and fill up one of their five available slots, or played by the matching house to activate their unique house power. Scandal cards come from a separate deck, and are played onto whatever house a player chooses, once again using one of that house’s five slots, but giving them two negative points. Players can also discard two matching suspicion cards to perform a masterstroke, adding or discarding scandals, or canceling house powers.

Each player’s house can be in one of three states at any given time: favored, disfavored, or vilified. Houses are favored if they have fewer than five cards played in front of them, and get an extra action on each of their turns. Once a house has five cards in front of them, they are disfavored; they turn their house card sideways and reveal their conspiracy, giving the matching house a scandal and gaining their power as long as they are still favored. However, if a disfavored house has at least three scandals, they are vilified, gaining a whole new set of actions that let them throw scandals willy-nilly, and score extra based on how many other houses they can drag down with them. The game ends when there is one favored house left at the end of an action, and players then total their points from their status cards in front of them, and their agenda. The player with the highest total points wins. This leads to a good game arc, where once a player falls into disfavor or becomes vilified, there’s a rapid crescendo of other players also losing their favor, until there’s just one left standing.

The wrench in the works is that everything from the cards in a player’s hand to what their agenda or conspiracy is to future actions can be used as bargaining chips in nonbinding deals. Other houses’ suspicion cards give players leverage over them- their cards can be traded to them so they can activate their power, but those same cards can also be played on them as a punishment. Scandal cards are rare until a house becomes vilified, but are powerful incentives when they’re still in hand. Working out who benefits from what is essential to victory, and all of this requires a lot of table talk to make deals, trade information, and forge temporary alliances in a fashion that feels like a cross between Cosmic Encounter, Diplomacy, and Chinatown. There’s a promise of an extremely unique and enjoyable game here that I haven’t really experienced before.

But the fact that Duhr is played almost entirely above the table is not just its greatest strength, it’s also its greatest weakness. It demands that not only every player really understands what’s going on, but also be thoroughly engaged in it. If just one player feels lost or checks out, the edges start to fray, and if that happens to more players, this game simply isn’t mechanically interesting enough to stand on its own. The game is nominally themed around squabbling fantasy houses, but it feels so thin and generic it’s never served to pull anyone in. Suffice it to say, every game I have played of Duhr has collapsed. Nonetheless, I’m convinced that one day I’ll be able to get a perfect group together and this game will sing to the heavens. Until then, the box is small enough that I’ll just carry it with me, a token of my belief in the possibility of its promise.

In the end, I’m left on the fence about recommending Duhr. It is a game that is unquestionably not for everyone, but may be the best game for the people it is for. The size of the box and advertised thirty minute playtime suggest that it’s light and airy when it’s anything but. I guess that, at the moment of me writing this review, it’s only $18 on several online stores, and for that price, if you think it may be for you, it’s worth taking a chance on.

Dûhr: The Lesser Houses

Good

The extreme amount and type of table talk that Duhr requires to work makes it a rough game to review and score. If you revel in the feeling you get when you have just the thing that another player needs, have no compunctions about who you help or beat down, and simply enjoy having your words weighing heavily upon whether you succeed or fail, this could easily become one of your favorite games. However, if a single one of those descriptions doesn’t ring true to you, it will probably fall flat.

Pros

- Simple rules

- Tiny box

- Promises greatness

Cons

- Not really mechanically engaging

- Can be really mean

- The rulebook is vague on some things