Eliza, the newest game from Zachtronics, is quite unlike any of the studio’s earlier efforts, but it feels in some ways like an extension of that work. Zachtronics is known for making deep engineering puzzles, the kind of games that draw you into intensely focused states of machine logic to solve puzzles like a programmer, or maybe even a computer. Eliza, on the other hand, is about as simple as a game can get mechanically. It’s a visual novel, meaning you’ll spend most of your time just clicking through to advance the story, rarely making any choices at all, and hardly ever making ones that affect its outcome. But beneath the surface, Eliza grows out of and builds upon Zachtronics’ other games conceptually. Previous Zachtronics games were about the human player making connections — literal ones, between engineering concepts and loops of code — to make a machine function as efficiently as possible. Eliza turns that on its head, asking what happens when people try to train machines to make emotional connections with human beings instead of doing that messy, difficult, inefficient work for themselves.

Eliza follows Evelyn Ishino-Aubrey, a woman emerging from a sort of three-year hiatus from her life to work as a “proxy” in a near-future automated counseling center. The clinic uses a program called Eliza (named after an early language processing computer that some speculated could one day help with talk therapy) to interpret patients’ statements and biometric data, prompting them for deeper reflection and offering suggestions in place of a traditional therapist. As a proxy, Evelyn’s job is simply to sit in the room with the patient and read the script that Eliza generates, in an effort to make the process feel less mechanical. Through a heads-up display, Evelyn can see all kinds of data, from the patient’s heart rate to Eliza’s assessment of their word choices, but is forbidden from going off script or speaking to them as herself. Outside of work, Evelyn is also trying to rebuild her life, reconnecting with her old coworkers and making new friends.

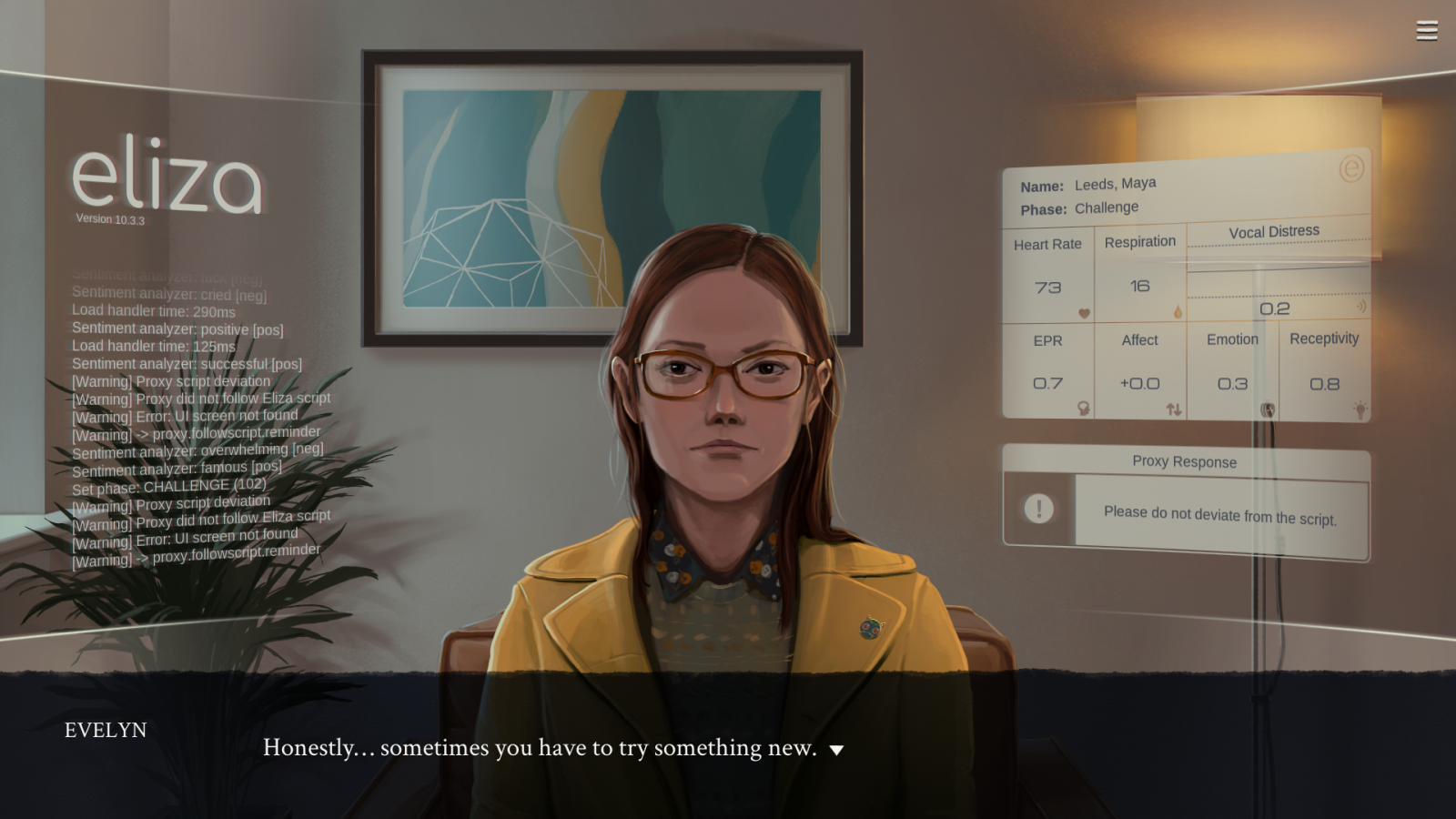

As far as visual novels go, Eliza stands out thanks to its high production value. It has basically no mechanical tricks up its sleeve (unless you count an optional solitaire mini-game), giving the player only simple dialogue menus and a cell phone interface to play with, but its art and sound design are top notch. Most scenes are illustrated with a beautiful, mostly static, hand-painted two shot of Evelyn and whomever she’s talking to, except for therapy sessions, which are shown from Evelyn’s point of view, Eliza HUD and all, with the occasional wide shot mixed in. Soft electronic beats score most of the game, sometimes turning mournful or bursting to life to underscore important moments. Almost every line of the game is fully voiced, excluding some light exposition and Evelyn’s inner monologue, and it’s uniformly excellent. Early in the game, Aily Kei’s closed-off, hollowed-out portrayal of Evelyn as a woman who, in her words, “slept into her mid-thirties” made even the small decisions I made feel important to getting her back on her feet, and when she finally broke out of her shell late in the game, I felt almost like I would if I were seeing a friend going through the same struggle. A therapy patient named Maya, played by Cissy Jones, was another standout for me, giving an incredibly natural performance as a young artist struggling with jealousy, insecurity, and self-loathing, but still being so charming and full of personality that I looked forward to every session when she was sitting in the chair across from me.

One of the first things you do in the game is complete Evelyn’s first shift as a proxy. Your very first meeting is with a difficult patient — a distant, nihilistic man who swings between anger and despair and grows distraught at the very idea of talking to you as a proxy instead of as a person. Even then, Eliza has an answer, prompting Evelyn to trick him into thinking she’s going off-script and give him her real name without asking how she feels about that. It’s an emotional, anxiety-inducing scene, giving the player no choice but to obey Eliza as this man, who seems clearly beyond the program’s ability to help, begs for even the smallest human connection.

This first meeting is one of the most intense, confrontational counseling sessions in the game, but even the more by-the-book encounters can be excruciating. Sessions with patients like Maya, for instance — who makes some statements that felt almost like they could have been taken verbatim from my own therapy sessions — can be even more heartbreaking, as they talk to Evelyn like she’s a real person, telling jokes, expressing gratitude, really reaching out, and all Evelyn — and by extension, the player — can do is give canned responses: Tell me why you feel that way, try this exercise, ask your doctor about this medication. All the while, your screen is taken up by Eliza’s UI. You see the cold calculus of it ranking statements as positive or negative, the way it’s scanning for patterns, dividing interactions into set phases (GREETING, DISCOVERY, CHALLENGE) and trying to usher patients through to the end of the session as efficiently as possible. At the end of each session, you see clients’ ratings of Evelyn as a clinician, complete with badges, levels, and even an optional tip from the client; a horrifyingly plausible, quietly dystopian outgrowth of the gig economy.

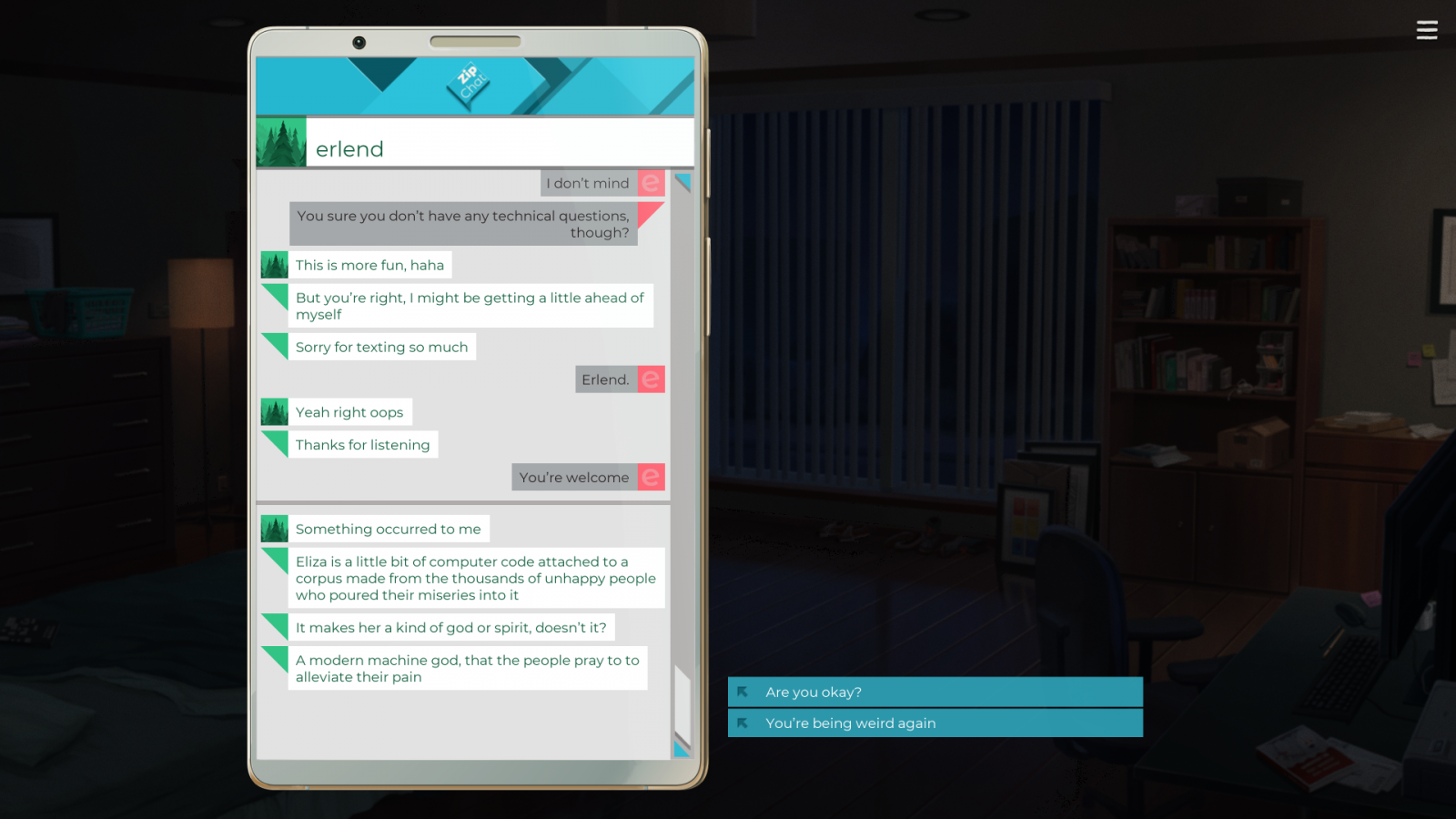

When she’s not serving as a proxy, the player follows Evelyn through conversations with people she knew before her three-year nap as well as a few new faces, all somehow related to Skandha, the company that owns Eliza. It’s a diverse cast of well-written, interesting characters, including the first asexual/aromantic character I can recall ever seeing in a game. The details of Evelyn’s former life are revealed through conversations with supporting characters, and she tries to make sense of what made her decide to drop out and where she’ll go from here. She meets with her clinic’s manager, a former Eliza engineer turned electronic artist, and the app’s new head of engineering, all with their own takes on Eliza: what it’s for, how effective it is, whether it goes too far or not far enough. Evelyn turns out to be an extraordinarily effective proxy and she’s courted by two executives at Skandha, one who wants to turn Eliza into a massive data-collection engine in the hopes of unlocking artificial intelligence, and another who’s developing an even more invasive technique to circumvent psychotherapy altogether in pursuit of his technological utopian quest to literally eradicate unhappiness.

Where Eliza’s proxy sessions show the player the present reality of its world, these conversations show the possibilities for the future. “Parametric therapy,” as it’s called, is clearly going to be a turning point for this world, and the way the game’s tech workers talk about it — fetishizing its cold, insular, hands-off approach to a sensitive human problem while brushing aside all the concerns about abuse and built-in flaws — is frighteningly similar to how large parts of the tech industry operate today. Eliza’s patients, and even Evelyn, are being used to benefit Skandha at least as much as they’re benefitting from the therapy. That’s not to say that Eliza is an anti-technology screed, though. While I found the ideas Skandha was chasing frightening and unethical, players are free to side with the company, and at least one of the game’s possible endings is optimistic about the technology’s potential.

Evelyn is mostly passive in these conversations, generally just agreeing or disagreeing with what’s being said; one of my very few complaints about the game is that her responses are often rather shallow or noncommittal and don’t develop her much as a character, but at least you’ll never end up knocking the story off course with a poorly considered dialogue choice. The writing can also lean slightly into the didactic at times, and there is some bloat in the middle where the game can get a little blunt and repetitive with its messages. Despite these issues, though, I found the game’s arguments fascinating and every one of its characters engaging.

Eliza may sound like a parable about the dangers of dehumanizing and privacy-invading technology, and to some extent it is, but it approaches the subject in a wholly original, profoundly compassionate way. Eliza is first and foremost a game about people. Not humanity as a whole, but the individual people who are exploited, overlooked, driven to poverty, and otherwise marginalized by modern, tech-worshiping, increasingly isolating capitalist society. Like many stories of this type, it’s concerned with where the line between human and machine is drawn. Not asking, as is usually the case, when a machine intelligence starts being considered human, but when our data stops being a part of us. When everything from eye movements to emotional descriptions are being recorded, analyzed, and used for financial gain, are we not in some way part of whatever is built with that data?

Eliza doesn’t offer a singular answer to the questions it raises, but it’s clearly a game with a strong viewpoint. While there are five different endings, neither of which is canonically “good,” it has a lot to say, and a lot to make the player think about. If there’s a central thesis to Eliza, it’s not about technology at all, but about human connection. Relying on Eliza — maybe on any rigid, top-down system that tries to be universal and unbiased — leads to reactiveness, to following patterns, to the idea that there is a correct way to approach life. Dealing with the tricky business of human interaction is more complicated and potentially more painful, but it also opens the possibility of real growth rather than mere pain avoidance.

One of the strongest condemnations of technology in the game actually comes in the form of an affirmation of human connection. Late in the game, you can read an entirely optional email from a woman who was once in a class that invited Evelyn as a guest speaker, and who had been inspired to pursue her current path as an engineer. Now a grad student, she writes that a high school class came through her lab and that prompted her to reach out to Evelyn. “Speaking to the kids, I realized that each of us pays forward our outreach, linking us in a chain that stretches backward and forward in time,” she writes. That chain is built of human connection, and purely technological solutions like Eliza, which can neither be mentors or students, peers or idols, break the chain, leaving even the people it helps utterly alone.

Near the end of the game, the player finally gets the option to deviate from Eliza’s script. By this point, even minor choices feel transgressive, dangerous — and humanizing. To reject the script and reach out in even a small attempt at connection seems radical and exciting, but also deeply frightening, cutting off Evelyn’s comfortable coasting for the chance at something better. There are no real consequences for doing so, and each of the game’s endings is still available, which undercuts the point slightly. It also veers dangerously close to a “magic bullet” portrayal of mental health, where one good therapy session is enough to turn someone’s life around, but manages to dodge it by having at least one patient who admits that he was hoping you’d just validate his unhappiness rather than asking him to face it.

In the ending that I chose, Evelyn doesn’t try to save the world or even to change it that much. Instead, she chooses to pursue a closer connection with one of her friends and do the best work she can, and in the process, she finds a moment of delirious happiness that made the whole journey worth it. Others may find a different ending more satisfying, but for me, this was the perfect choice. No one is trying to replace therapists with computers, at least not yet, but in a world increasingly obsessed with building machines that understand us better than we understand each other or ourselves, Eliza’s insistence that the simple act of reaching out can be enough is worth paying attention to.