When you read through as many TTRPG books as I have, you start to see some patterns emerge. Things that may set an expectation or opinion before you fully recognize the whole work. Castles and Crusades is a good example of a game that seems to follow some patterns I’d recognized, only to surprise me later.

The first surprise was versioning. I’ve been aware of the existence of Castles and Crusades for decades, having seen it on the shelves alongside books for D&D’s 3.5 edition. I was shocked to learn that, technically, this is still the first edition. Instead of editions, C&C updates the core game via print runs, which they’ve done nine of so far. The differences between the printings range from spelling corrections and new art or print color, to adding new classes or doubling the level cap to 24. In other words, very tiny to huge…though the intent is that the core experience doesn’t change much.

The next surprise was the core books themselves. Castles and Crusades has the very common three book layout: one for players, one for the game master (called the Castle Keeper here), and one of monsters for the players to fight. The difference here, according to rumor anyway, is that only the Player’s Handbook is truly required. All the core rules for playing and running the game are contained in the PHB. Having the Monsters & Treasure book makes things much easier on the CK, but it’s not an absolute requirement. Meanwhile, the Castle Keeper’s Guide is filled with entirely optional and alternative rules to run the game with.

The final surprise was about the style of the game itself. Since it was released in 2004 under the OGL used for Dungeons and Dragons 3rd Edition, I expected a game with offshoots of 3rd Edition mechanics. Something more like Pathfinder 1st Edition. Instead, this is a game that is closest in spirit to Advanced Dungeons and Dragons. I primarily see AD&D 2nd Edition at work here, but I played a lot of 2nd Edition so that could be personal bias.

If you aren’t familiar with 2nd Edition, it’s easiest to view it as a sort of foundational work in modern fantasy gaming. In most modern games—be they table top, board, or video—druids shapeshift, wizards throw fireballs, and paladins smite things. They did these things in 2nd Edition, which made it into the later editions of D&D, into popular computer games of the 90s, and then into MMORPGs like World of Warcraft. Now, 2nd Edition may not have been entirely original in creating these mechanics, but it did put them all in one place for an entire generation of game designers to be influenced by.

Of course, 2nd Edition is equally infamous for its use of oddball mechanics, like having percentile rolls on “stealth” based skills, but d20 rolls on other skills. Or it’s elaborate saving throw matrices. And probably the most infamous and unintuitive system of all, the “To Hit Armor Class 0” combat mechanic.

Enter Castles and Crusades. A precursor or proto-example of the “Old School Revival” movement, this game tries to preserve the feel of AD&D while smoothing out many of those disjointed mechanics. Most checks are made with a d20, rolling to hit uses an ascending armor class, and other streamlined ideas introduced in 3rd Edition and still in some form of use today. The end result is a rules system that could have been D&D 3rd Edition from a divergent timeline.

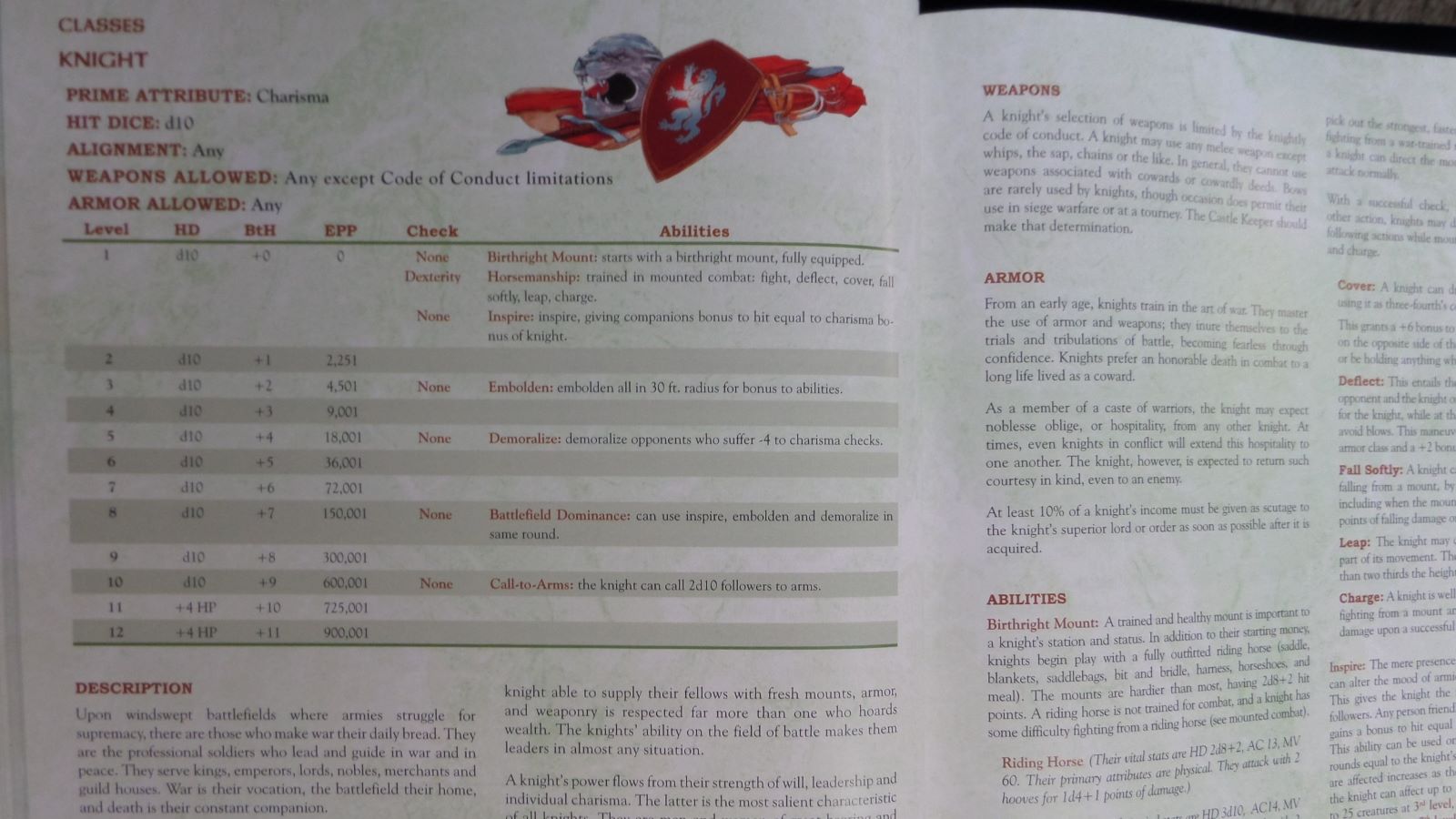

Knights have many mount and aura-based abilities.

For those who’ve never played AD&D or one of the modern OSR style games, you might be wondering what the “feel” means. It’s a big question with whole books written on the subject. To keep it short, a sweeping generality would be that they have a heavier focus on how the players want to play over what the characters can do. The original Tomb of Horrors could be viewed as the ultimate example, where character class and levels mean almost nothing and success hinges almost entirely on player ingenuity. Obviously, most sessions aren’t going to push players as hard as Tomb of Horrors, but that is the direction of play that C&C tries to move toward.

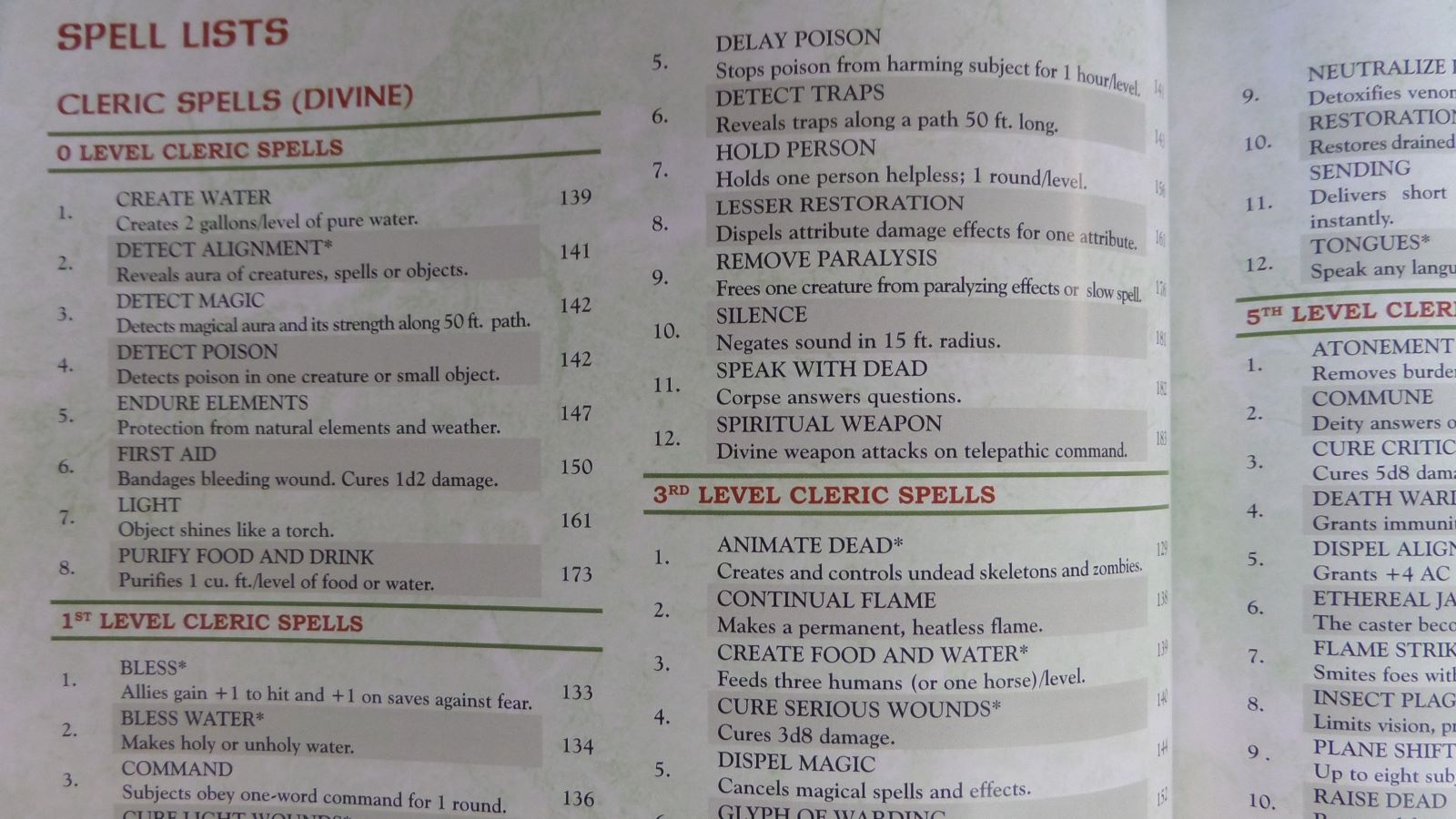

The class and race options are drawn from what are now fantasy standards. The druid, monk, wizard, fighter, elves, dwarves, etc, operate largely as you would expect from popular fantasy gaming. Of the three “less traditional” classes, the knight class is a mount focused leader, and the assassin uses disguises and lethal hits. The most unique class is C&C’s version of the illusionist, an arcane caster with some healing and a substantial amount of exclusive spells. There are thirteen classes and seven races in total, and several hundred spells to parse through.

The spell lists are very nicely organized.

Like AD&D, there are no subclasses or feats in the Player’s Handbook. Most characters will have nearly all of their abilities within the first few levels, with later levels simply improving what they already have. Multiclassing and the “class and a half” system are presented as options for a more complicated character build, though both are done at the cost of a slower progression.

There’s also no skill selection. Instead, skill checks use what Troll Lord Games calls the “SIEGE Engine”. It is an attribute based skill check on a d20. Each class has a fixed “primary attribute”, and the player picks another to tag as primary. The player explains what they want to do, the Castle Keeper decides which attribute is used and sets other relevant modifiers. The base difficulty is 12 for a primary attribute and 18 for secondary attributes. Players of TTRPGs are notorious for getting locked in on what’s on their character sheet. If something isn’t listed, or it’s something the character doesn’t excel at, then the player may not treat it as an option. The SIEGE Engine opens up this aspect to anything a player can think of, with a simple structure for resolution.

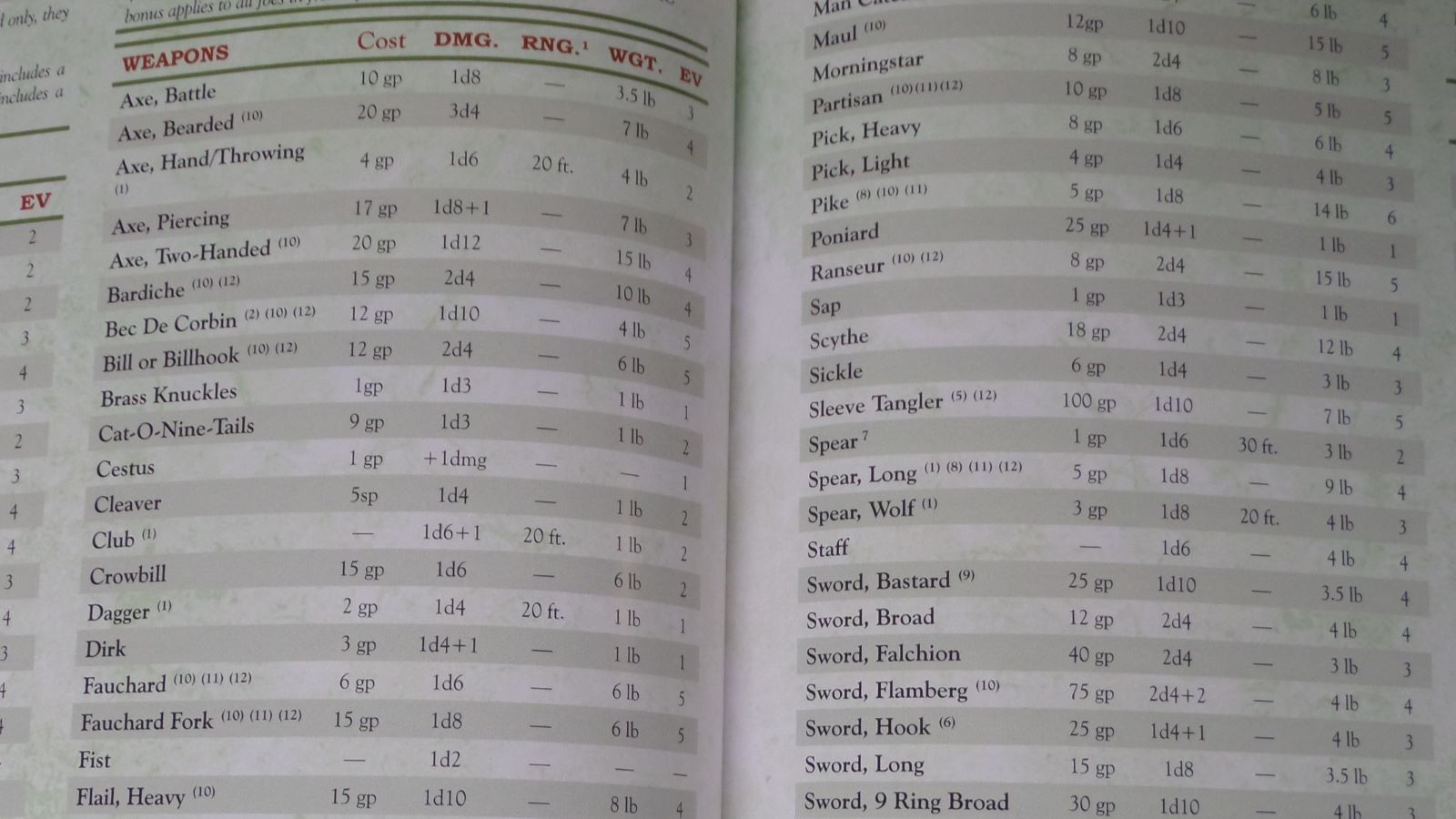

While Castles and Crusades might streamline some mechanics of the earlier editions of AD&D, it embraces other aspects whole-heartedly. This means class specific XP tables; by the time the paladin hits 8th level, the monk has been there a while and the rogue is hitting 10th. It means fire and forget spells, with multiple copies having to be memorized if you want to cast the same spell more than once. And of course it means having an absolutely staggering variety of polearms.

Every name you don’t recognize is probably a polearm.

It also means some of these class abilities and character rules are very restrictive, specific, and written in such a way as to justify why these rules are as they are. The basis for C&C comes from a time when D&D was old enough to have garnered a lot of mechanical discussion, when the stapled pamphlets had become thick hardbacks that said “Advanced” on them. More modern retro-clones usually skip or retool stuff like this into simpler language, but that style of rule description has been transferred into C&C almost unchanged. Some are forgivable or don’t impede the fun of the game too much. Others are strange, unintuitive, or overly intricate, forcing the players back the book again and again while not adding much to the play experience. It can give a feeling of not having focus, of different rules being written by different authors at different time periods.

Still, there is plenty of fun to be had. The book lays a wide enough groundwork for even a long form campaign. And while it doesn’t focus too heavily on any one type of playstyle, it doesn’t exclude any either, something that can’t be said for some OSR games. The system also has the advantage of being almost instantly compatible with every adventure, module, and campaign setting for D&D to come out in the 80s and 90s.

Castles & Crusades Players Handbook

Good

The Castles and Crusades Player’s Handbook presents substantial mechanical improvements over the versions of D&D that inspired it. C&C is at its best when presenting original ideas, but often clings too tightly to legacy styling.

Pros

- Re-creates the ambience of AD&D with improved rules

- SIEGE Engine system frees characters to try nearly anything

- Massive treasure trove of compatible material exists for this era of play

Cons

- Still carries some of the mechanical issues from that era of design

- Rules don’t seem cohesive or equally updated