Keeping true to many of the 80s action films that inspired Countdown: Action Edition, Dog Might games has delivered an experience that is full of heart and hilarity, but lacking in the follow through that would make it more. Countdown sets one player as an Action Hero, sent into an active hostage situation in which the Villains have hidden themselves among the Hostages, forcing that hero to determine who to set free and who to leave behind before the bomb goes off. While the game does possess a degree of style and charm, mechanically speaking it is too ill-conceived to be able to recommend, especially when compared against its competitors.

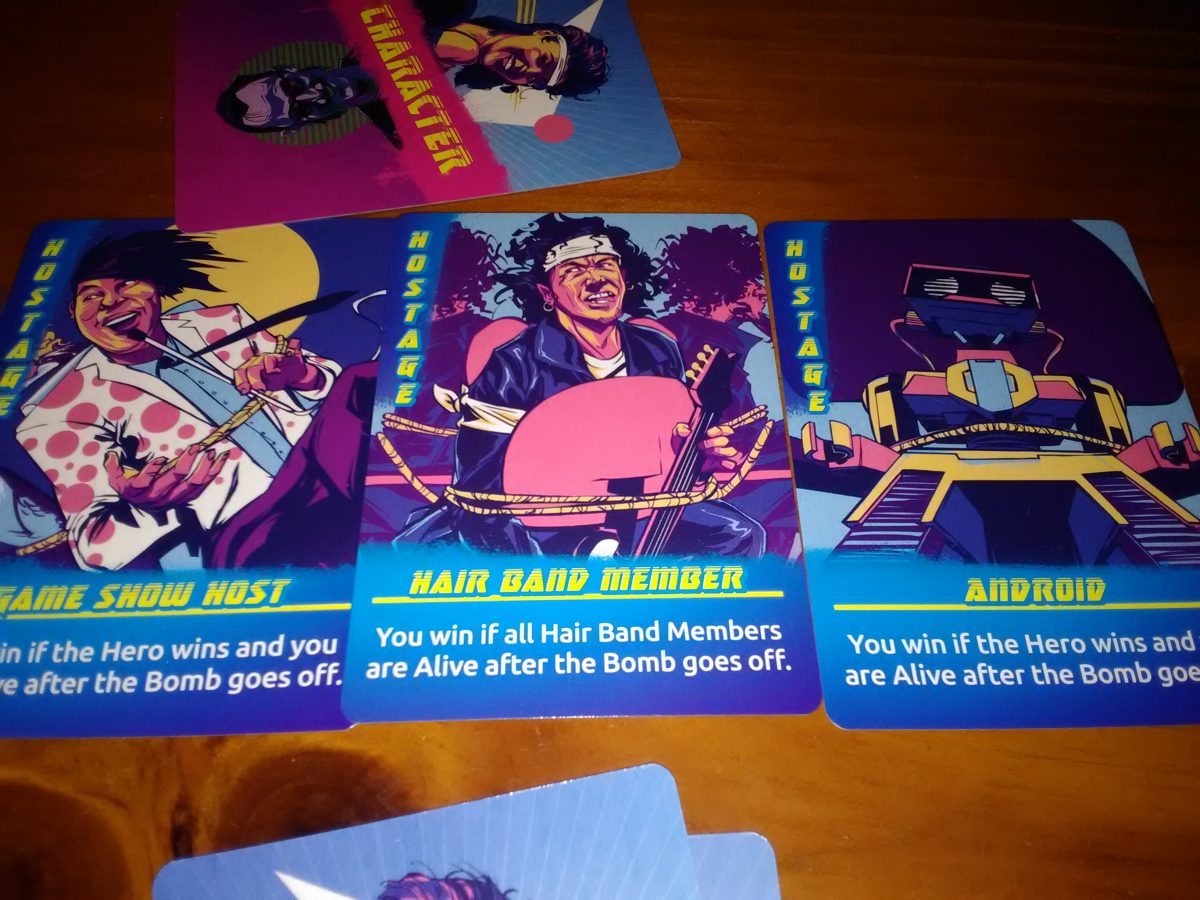

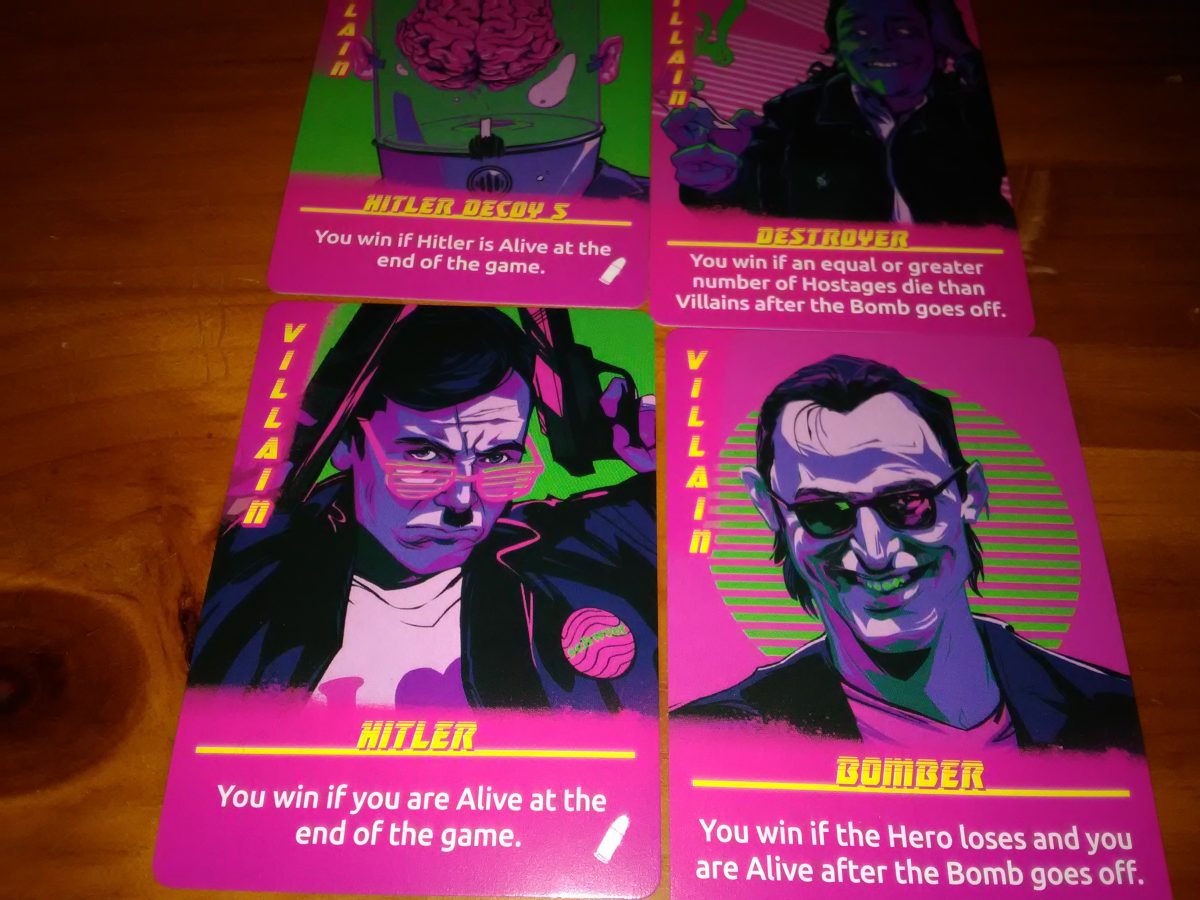

Countdown’s main components consist of a few small decks of cards. You have the secret roles, between Hostage and Villain, as well as character cards for each, representing your identity within the game. The players also have Action cards which grant them singular extra abilities, which are best explained once you have a more complete understanding of the game.

The art takes its cues from what we now pretend was an 80s aesthetic (not a critique of this game as much as the general revisionism we employ about the era). It’s all harsh shadows and loud neon colors that sell a ton of character and amp you up for the fun time you want to have from a game like this. The cards perform their function well, telling you the information you need to know while selling a lot of flavor in the process. I’m sure the temptation to go too far was there, but Andrew Thompson exercised a lot of restraint in an artstyle that could have gotten out of hand. The visuals are likely the highlight of this game, including a variety of characters with inviting details thrown in to give them extra characterization.

To set up, you will choose the Action Hero…somehow (the rulebook gives no suggestion on how to make this decision). You will then shuffle the role cards, their number determined by the number of players, and remove one role card at random, to create uncertainty about how many Hostages or Villains there are. You will also create the Countdown deck, which is made up of three piles of cards, broadly speaking the Three, Two, and One decks, denoting the ticking clock. The Bomb itself is placed within the bottom deck somewhere, and you don’t know precisely how much time is left before the game is over.

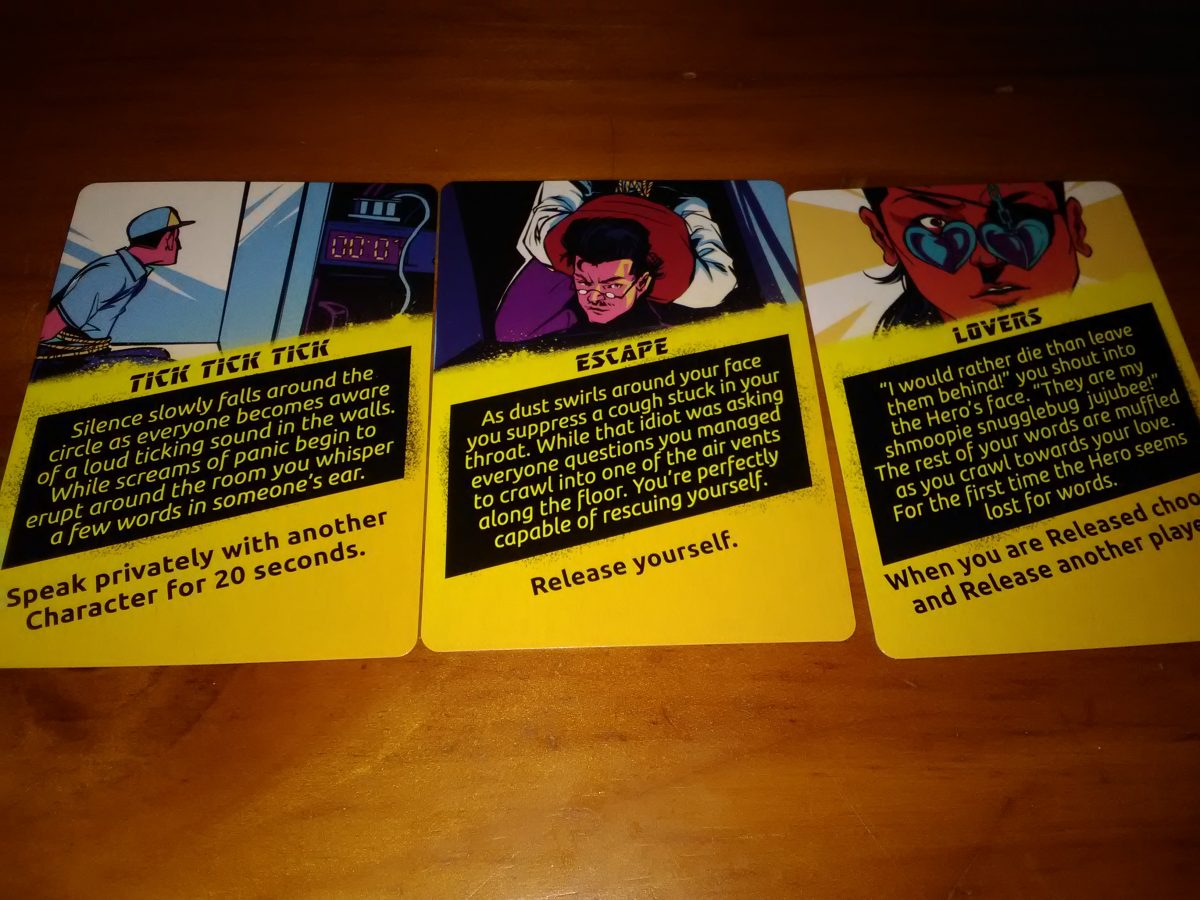

Each player other than the Hero will get a random role. They will then, starting with the player to the Hero’s left, search through the character deck and choose one to their liking and allegiance. This necessarily removes choices for each other player, except for the final player who may choose from all discarded cards. Each player also receives an Action Scene card. These cards have special abilities that can have a powerful effect (in theory) such as the ability to immediately release another player, look at someone else’s role card, speak secretly with another player for 20 seconds, and so on.

During gameplay, the Hero will flip over the top card of the bomb deck and take two of the three actions available, such as asking specific questions, asking yes or no questions to everyone at the table, and freeing or capturing individuals. The players can talk as much as they want, but must do so openly. In response to questions, which often ask about the identities of the characters, everyone must answer a question if asked. The wrinkle is that Villains may lie about whatever they wish. At any time, any player may play their action scene card, for brief (and depending on circumstance, potentially useless) narrative control. The game ends once the bomb finally goes off, killing everyone who is not released. You then check to see if your individual win condition has been met, and the Hero finds out if they have been getting played or saving innocent lives.

While there are some sparks of creativity in Countdown: Action Edition, their only effect is to highlight the grand void of potential it leaves unused. Frankly, this design is not fit to its purpose, and enjoying a game of Countdown can only occur despite the rules, not because of them. This design contains a few large missteps, but the largest and most significant is the lack of information the Hero actually has to evaluate, and the way this destroys the game’s ability to deliver a fun time. You see, hidden role games are predicated not just on the uncertainty of who is on what side, but in using the scant information you have to find that out. The problem with Countdown is that it gives you no such information. For all the hemming and hawing about roles, characters, and questions, the Hero has no practical way to find out who is on what side, and the Hostages have no way to help the Hero.

The Hostages have to tell the truth about their roles, but the Villains don’t. They can lie about whatever they want. As long as they don’t make some egregious error in contradicting themselves, you have no way whatsoever to discover their true intentions. Everyone can just make up a character, or even use one that they have already seen in the deck, in this or previous games. These characters don’t have any special properties or abilities, so how can you possibly use that to determine who is telling the truth? Ask them to describe the art of the card in front of them?

Yes, players have access to Action Scene cards, but these cards are situational, singular, and ultimately subject to the same issue as everything else: Villains’ ability to lie without restraint.

In Resistance or Secret Hitler, you have pass/fail missions that can tell you information about specific players. In One Night Ultimate Werewolf, you have discrete roles among the players, and ways to logically determine the effects of any contradiction, and therefore who is likely to be lying. In Spyfall, just as in this game, the characters native to the scene have defined roles. In combining elements from these games, it fails to implement the aspects of those games that made them actually function. It doesn’t have the necessary limitations or goals that would force the Villains to reveal themselves. The Hero/Hostage combination has no direct information. The Villains know more than anyone else at the table, and nothing forces them to reveal themselves except absurd incompetence. As long as any of them can stick to a basic narrative, they win the game, and nothing in this game’s mechanics or the players at the table can shake that. This is not to mention the fact that the Villains know one another’s identities, but honestly it doesn’t matter at all, because they have no way to work together unless they want to join in casting aspersions on other players. But even this might be a mistake. Why do so and maybe risk being called out for being antagonistic when you could instead just play your role and get out alive?

The Hero dynamic also removes any substantial gameplay from most of the people at the table. Instead of interacting with one another to find the truth, everyone has to spin themselves to the Hero, the sole decision maker among the 5-15 of you. The more people there are, the less any individual gets to participate. Sure, the Hostages could try to help find the Villains, but how? If any one of them knows specifically that a Villain is lying, they have no way to prove that to the other Hostages. They have no objective information, and most of the time they have nothing to actually do. The most that can happen is that the game will devolve into a shouting match at the Hero, who has to choose who to examine and about what, thereby also deciding who gets to participate in the game.

This is made all the more incomprehensible by side goals that both hostages and villains have, which may contradict the rest of the team. Some of those goals involve specifically killing members of their team, something they may not want to reveal. This creates a tangled mess of four or five different factions at a table working at cross-purposes, with little agency, no information, and very little to actually do when you get down to it. I had my doubts reading through the rulebook, but the moment my heart gave up on the game was when, about 20 minutes into it, one of my players turned to me with dismay and said “I just don’t know what I’m supposed to be doing here.” I had no idea what to tell them.

To illustrate what I mean, let me put you in the shoes of the Hero for a second. Two people, for instance, say that they are the janitor. No one else at the table is saying anything, because what could they possibly say? Other Hostages don’t know their loyalty, and Villains have no way to objectively describe for you why they think one person is more trustworthy. Neither do you for that matter. While you are constantly gathering information, none of it is useful for anything. You are going SOLELY off of how effective you think either person is lying, and your ability to detect those lies. The entire time you are making this determination, the other players are sitting around waiting until they get to be a part of the game too. If you do take this game up to the ludicrously high player count of 15, that’s all the more “information” you have to sort through and all the more time that over 10 of your friends have to sit around on their hands.

Countdown is distinctly almost fun. It has so many glimmers of a good time, buried somewhere in there. While you are teasing out that someone is lying, and different groups are starting to form between the players, edging towards differing goals, you can be forgiven for thinking that you will end up enjoying the experience. But somewhere along the line that fades, as the Hero realizes they need to make a decision but don’t have the tools necessary to do so.

The most fun you could have with this is by surrendering to the fiction of it, letting yourself ease into the cliches of an action movie and the ticking clock that will seal your fate. There is some enjoyment in spinning this tale of woe, but one that would be better suited to Fiasco, if you wanted the same scenario and skills to apply. This design is not worthy of disdain or hatred, nor are any of its designers, but I can’t shake the feeling that every piece of this you might enjoy is implemented better in other places.

Countdown: Action Edition

Bad

Countdown Action Edition contains some novel ideas about engaging a group of players with hidden roles, but those ideas are so numerous and so contradictory that none of them come through effectively. You might be able to get some enjoyment out of the bombastic action espionage that the game tries to convey, but if you are in the mood for social deduction you may have better luck elsewhere.

Pros

- Slick, imaginative 80s art

- Engaging theme to get you into the right mindset

- Simplistic rules make it easy to start playing

Cons

- The Hero has more to do than anyone else at the table

- Too little information to make educated decisions

- Contradictory goals confuse the narrative