When Arrakis was first announced a few months ago as a reskin/redesign of an ’80s area control game named Borderlands, I was pretty optimistic. Say what you will (and I have) about Gale Force Nine’s track record with their original designs, their success renovating the antique Dune speaks for itself.

In a way, my optimism was validated- there are some really cool ideas in this box, especially with the standout water debt mechanic. As players jostle for the resources and production sites that will allow them to build the all-important sietches that double resource production and ultimately give them the win, territories and the tokens inside them will inevitably change ownership. In most area control games, losing territory is a painful experience, and while Arrakis is no exception, offenders have to provide their victims with water debt tokens as a salve. And a potent salve they are, as water debt is the most versatile and unconditionally useful mechanic I’ve ever seen. These tokens can be returned to stop their owner from attacking, or to ignore hostile regions for your own attack deep into their territory. They can even be turned in to generate resources. Of course, as valuable as they are, they can also be used as a hot commodity in trades with other players. But water debt isn’t the only neat idea in Arrakis. Remember those resources you’re going to be fighting over? They don’t just magically teleport to some resource pool when they’re produced. Instead, they pop out on the same map region as their production site, and a fair amount of the game is working out the logistics of getting stuff where it needs to be to be converted into the bevy of development tiles. I was also initially enticed by the variable map setup, where rock faces make some borders harder than others, production sites are distributed randomly, and then players draft starting regions. The good stuff here isn’t just mechanics- Arrakis has the best first-party insert I’ve seen outside of Twilight Imperium. Otherwise, I’d describe the production as adequate- the punchboard is thick enough, and the cards don’t feel flimsy, but there’s nothing to write home about or impress anybody.

Unfortunately, just like a cute guy that won’t shut up about crypto, as much as I wanted to like Arrakis, we have some fundamental differences that I can’t reconcile. I may as well start with the rulebook, which is harder to parse than the more difficult Faulkner texts. The main issue is that it is formatted by the guy in your group that can’t settle on an order to teach the rules in, so it’s constantly referencing ideas it hasn’t taught you yet, giving you page numbers to skip to like a choose your own adventure. The opening pages, usually dedicated to introducing core gameplay concepts or victory conditions, are instead a bunch of irrelevant fluff and a giant example of the randomized setup, not that it or any other depiction in the rules gives a balanced alternative for first-timers. It goes on like this, haphazardly throwing information at its reader, including a personal bugbear of mine, using its own bespoke terminology instead of industry standards. Seasoned gamers will be able to immediately recognize a game round, so why are we obfuscating it by calling it a cycle? My stomach lurched when I got to the table that explained the conditions under which basic phases like resource production do or do not occur, and it honestly didn’t look better from there. Understanding borders and movement has a quantum mechanics feel to it, as which tokens can cross which borders (and how many) depends upon a combination of factors including what combination of tokens are present and whether or not there’s rocks on the border. While this focus on logistics is a neat idea, but in an area control game, it presents a readability nightmare.

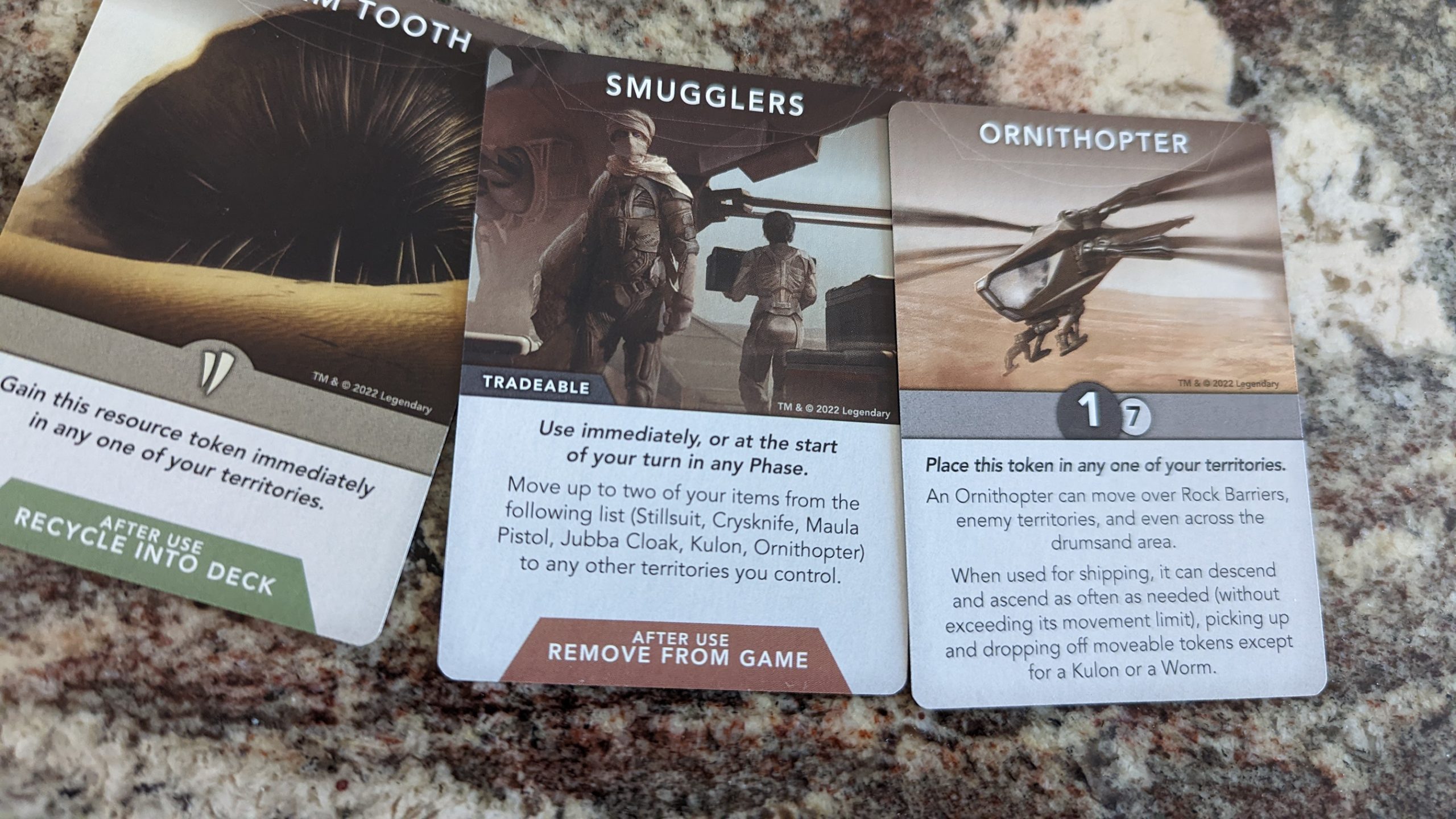

Which brings us to the action phase, where players can choose to attack or draw cards from the scavenge deck. Attacking seems simple enough: you just place the attack token in the region you wish to attack. Instead it’s another unfortunate combination of interpreting vague rules and deciphering opaque board states. The attacker makes one movement into the indicated region, with the option to pick up, but not drop off, tokens along the way. Then players’ combat strength is calculated by adding their tokens in that region to their tokens in adjacent regions, with the exception of those separated by rock barriers, with the secondary exception of those containing kulon tokens. Somewhere along the line, the defender can drop two of the attacker’s water debts into the region to stop the attack, but the timing for that, and what one does with them afterwards, is unclear. If this happens, or the defender wins, the attacker is free to attack a different region, or scavenge instead, but once again, the rulebook doesn’t explain what happens to the tokens the attacker moved in. I assumed that the defender just gets them, but any clarity whatsoever would be appreciated. Moving on to the scavenge deck, it may be the most high-variance mechanic I’ve ever seen in a board game. The cards you draw can give you anything from a single resource to an ornithopter, which has seven movement and ignores all movement restrictions, making the logistics puzzle of getting the resources you want where you want them obsolete.

Finally, I’ve got to address the end of the rulebook, which is chock-full of rules that don’t make sense or just make Arrakis feel like a lazy design. First off, there are rules that allow for house rules if everyone agrees to them, which first struck me as neat, but after some thought, came across as kinda lazy, as most games nowadays don’t need house rules, because the design is properly tested and balanced before being sold to customers. Similarly, there are rules for when players leave mid-game. Once again, this seems nice, but if people are quitting your 90-minute game before it’s finished enough that you need to make a rule covering it, that would seem to indicate that there’s a greater flaw with your balancing that should be addressed. The rules that really flipped the switch in my head from “this is a cool idea with some issues” to ” Gale Force Nine couldn’t be bothered to finish their game before selling it” are those regarding formal alliances. Being in a formalized alliance provides a bevy of benefits, from combat and logistics, to simply lowering the number of sietches required to win the game. However, all players have to approve a formal alliance, and the strategy section in the back admits that the other players probably shouldn’t approve of any alliances, and suggests that heavy incentives and rules tweaks in the other’s favor may be necessary to gain the table’s approval. It feels like the designers saying “hey, here’s a cool idea for a game mechanic, why don’t y’all finish it for us?”

Unfortunately, this feeling permeates the whole game, as if Gale Force Nine sent a box full of components and play suggestions, expecting customers to make their own game with it.

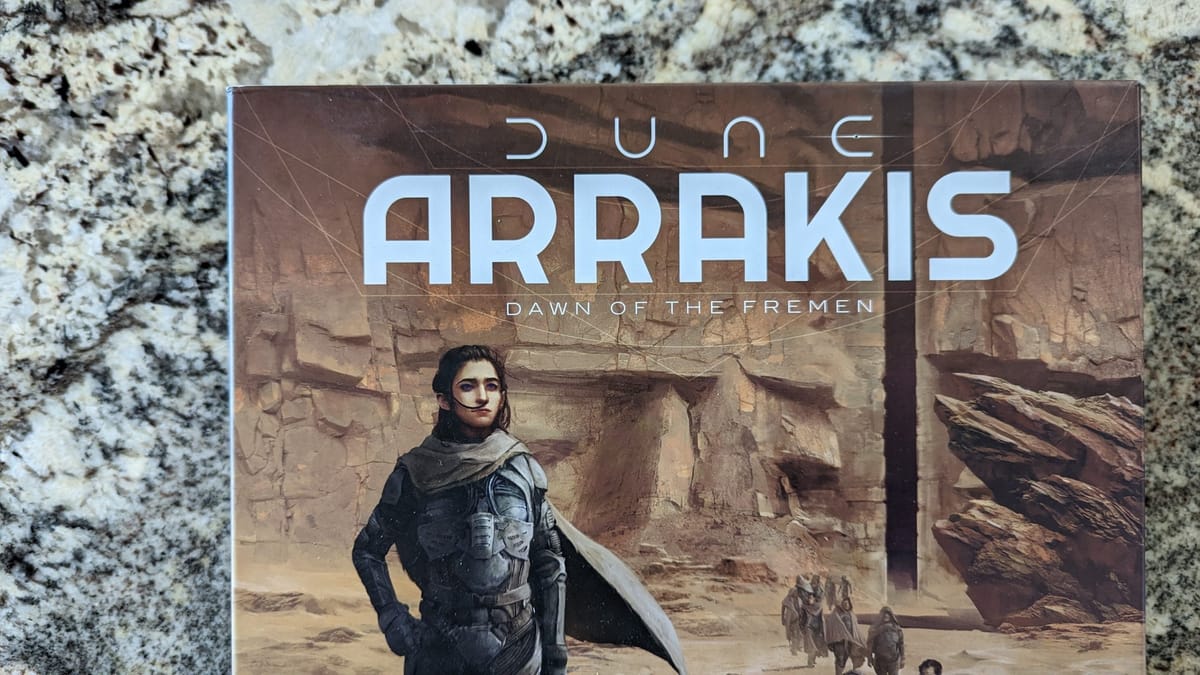

Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen

Bad

Arrakis has some good ideas that I'd definitely suggest aspiring designers or just fans of game design check out, but there just isn't a complete game attached to them to justify the price tag.

Pros

- Water debt makes losing territory feel much less punishing than it does in an average area control game

- The puzzle of moving resources from their production sites to the regions you want to build in is interesting and fun

- The provided insert is quality enough that I had no need to raid my stash of baggies for a storage solution

Cons

- The rulebook is confusing and vague

- The usefulness of scavenge cards varies wildly

- The game itself admits some concepts aren't fully fleshed out, and leaves consumers with the responsibility of making the game they bought a complete game