Some ideas can look good on paper or in an echo chamber and need a stranger’s perspective. For board games, fresh perspectives can be especially hard to secure. Each tweak to a design demands a new, complete playthrough. Each play needs a full table of players. Eventually, that table needs fresh blood to cut through “meta play,” the patterns which emerge within closed groups and make a design’s merits hard to see. Then, when a designer’s on their eighth iteration (or their sixteenth, their hundredth…), strangers become few and far between.

That’s where conventions can help. Over thirty thousand people from all over the world attended PAX Unplugged this year, eager to play anything that looked like a game. Hundreds of designers and players coursed through the unpublished hall in two hour waves. None of these tables was empty for long.

A convention’s “unpub” hall is a unique experience I recommend to fans of improv, D&D, and spontaneity in general. This is your chance to see designers create in the open, to hear their synapses firing as they squeeze every drop out of this precious resource. You and the designer are looking at rough clay together, imagining all its beautiful and ugly forms.

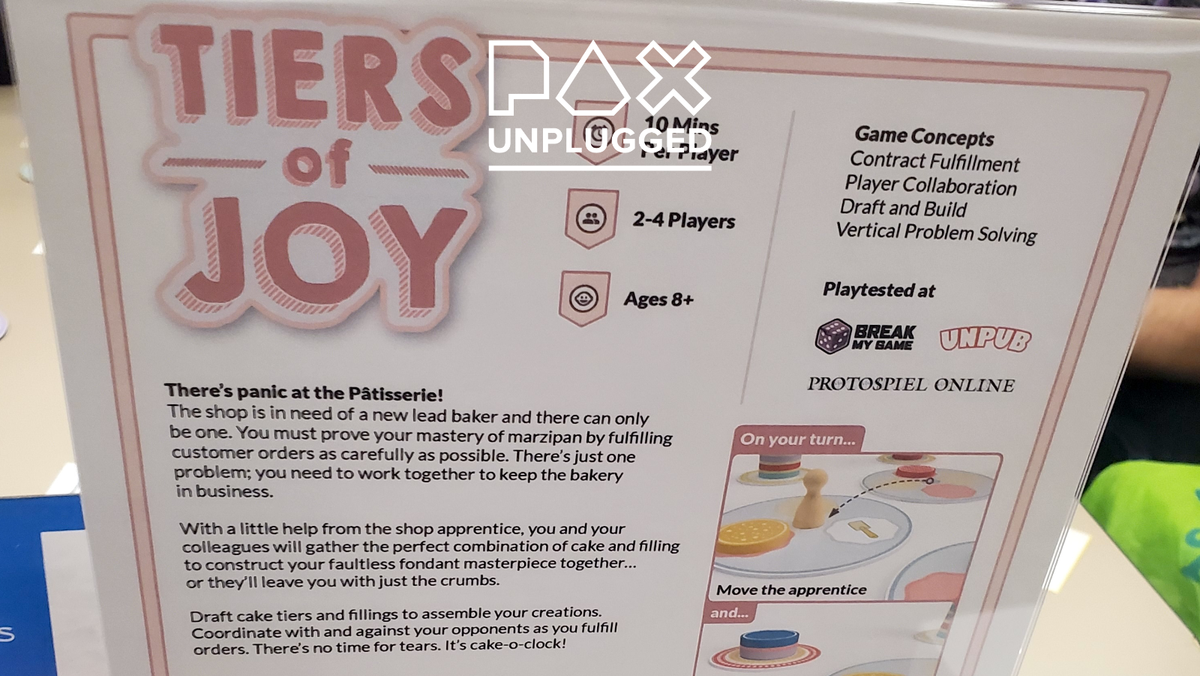

Tiers of Joy

I’ll flout tradition here and put the best first. Tiers of Joy has a polished, satisfying gameplay loop. Add some modular content, a few wrinkles for people on their fourth or fifth play, and it’ll be ready for publication.

Players take on the role of bakers constructing layer cakes for hungry patrons. At the beginning of the game, they receive three recipes with exacting color and order demands and will score points based on how closely they adhere to the recipe.

The catch is that they have to collaborate on two of those recipes with the bakers to their right and left, and only their lowest score will count. Of course, they can always divert ingredients toward a third, private recipe whose points are theirs and theirs alone….

Every round has two phases. Phase one consists of moving the pawn (Master Chef) between coasters and choosing fillings and layers (thick cylinders = filling; wafers = layers). Players take turns collecting fillings one by one until they clear the coasters, and each filling comes with a layer matching the colored spot beneath that filling.

It’s similar to Azul’s drafting, but less cruel. You can’t create a “musical chairs” scenario and stick someone with a bushel of negative points. While the Master Chef can’t use the same coaster twice and you can thus block the next player from a filling they need, the level of spite runs low here. Actually, Joy rewards planning your draft with the next player—half your points come from them.

In Phase Two, you assign filling and layers to your orders and haggle with your fellow chefs. There was some lively horse trading. Once in a while, we caught each other siphoning vital supplies to build our personal cakes. We would cajole, trade future favors, and promise to make up for our selfishness in the next draft. Ignore what BGG will tell you: Tiers of Joy is a negotiation game.

Start to finish, it took about thirty minutes and I anticipate that number dropping. The scoring’s simplicity helps a lot in this regard. Either your cake has the colors in the right order or it doesn’t. Compared to Between Two Cities’ knotty resolution of the same general concept, that’s a breeze.

Its core gameplay’s tight, lean, and perhaps a tad…bare. Designer David Masnato introduced a “topper” layer which, if used to complete a cake, netted some bonus points. Overall, we (the playtesters and I) felt apathetic toward its inclusion, but it reminded us that this attractive package has some gaps.

Played with the same personalities and in quick succession, and this is the sort of game which encourages that, Joy could become scripted. Once you figure out predictable rules for trading favors with your neighbor, you’ve solved most of the game’s challenges. Adding a means to disrupt those partnerships or bend the rules of the Master Chef could grant Tiers of Joy much needed longevity.

But in the grand scheme of things, to be left wanting more is not a poor state of affairs.

Starving Artists

“I think we got too many pieces,” Arboretum designer Dan Cassar told us, “so keep two of each color and dump the rest.”

Before our session of his new project, Starving Artists, I observed the last playtesters finishing up theirs. I’m convinced that only 75% of the rules he taught them survived the transition to our group. Cards and components, past and future additions, were piled up around the table like a carpenter’s wood shavings. Cassar’s passion and ruthlessness toward his own ideas impressed me to no end.

It wasn’t the most orderly playtest in the hall. Sometimes the rules explanation suffered because he (understandably) needed a second to sort out his current rules and cards from the ones he used a half hour ago. But, in exchange, we experienced the thrill of an excavation. If an artist has the right temperament for intense revision—a killer instinct for keeping what succeeds, cutting losers, and prizing its core conceit—this philosophy dazzles.

This reminded me that there’s more to an “unpub” hall than a preview of next year’s fashions. We get to see a craft normally practiced in secret; we get to see it performed.

This means, unfortunately, that few specifics about my play of Starving Artists will survive or matter. Let’s focus on that core conceit.

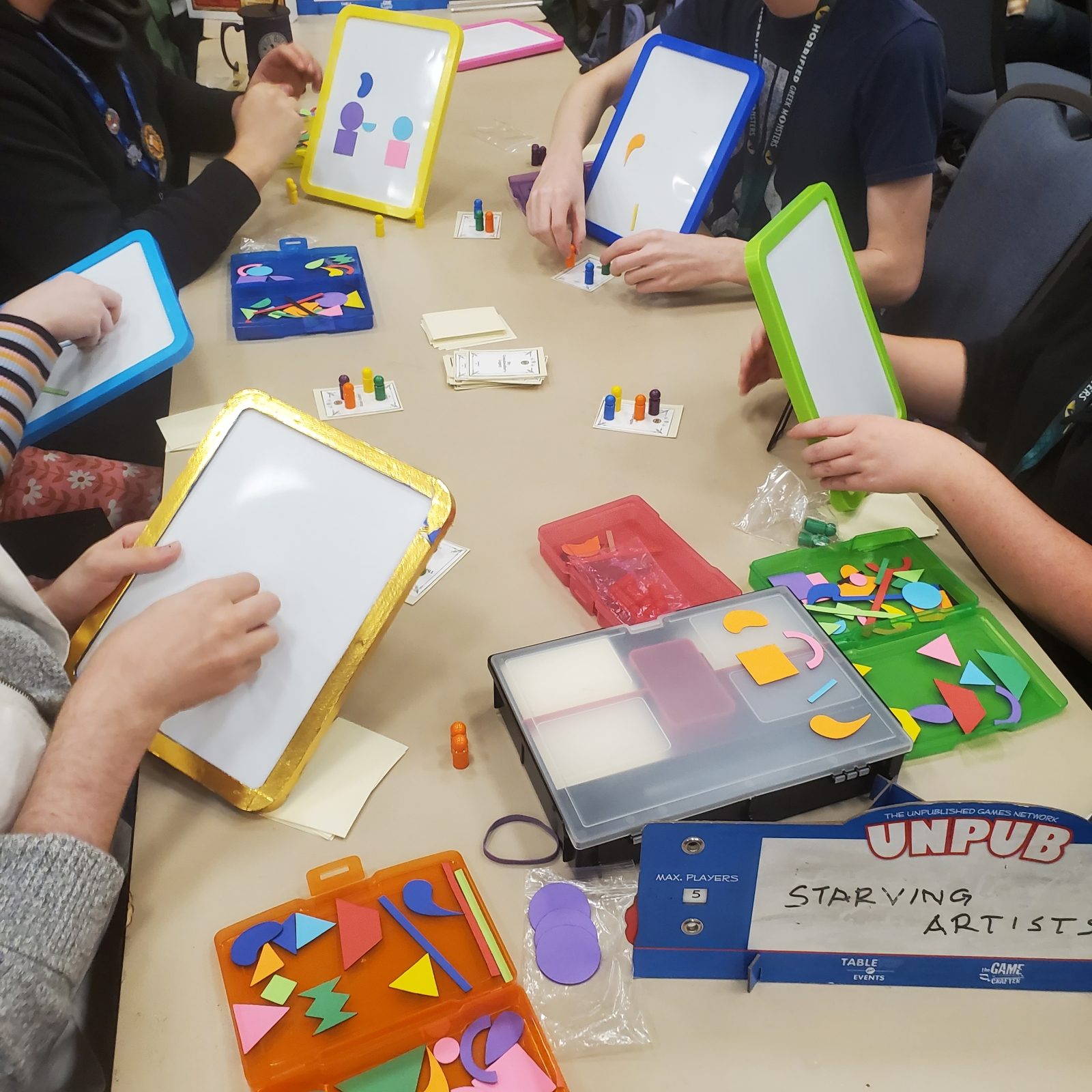

Everyone receives a whiteboard, a box of geometric magnets, voting tokens, and some cards with thoughts on them. Those thoughts trend toward the angsty, the froufrou, the “unbearable lightness of being” variety into which people read everything or less than nothing. They pick a thought they can work with and create a corresponding image on the whiteboard with their magnets. They exhibit the resulting (disaster)piece and place its “title,” the inspirational card, face down in front of it.

Everyone provides an alternative title for each others’ works, putting their contributions face down on top of the original titles. The individual piles are shuffled and revealed. Then, considering each artwork and its titles in turn, players vote for the card which, they suspect, belongs to the artist. Artists score points for every correct answer. Others score points for every vote their fake title captured.

What scoring means in Starving Artists will fluctuate for a while, I think. In this version, it meant losing, keeping, and taking pieces from each other. It was refreshing to see victory measured without points, as is the case in Dixit. It nevertheless feels hazy and unintuitive.

But that’s a matter of time. What about that core conceit?

Dixit, whose influence and close resemblance merit a place in this conversation, is about surrealism. It displays a knowledge of technique, of proportion and color and realism, before it alters its logic. It’s about dream interpretation and asking what its images mean, not if they mean something.

Starving Artists explores the goofier territory of abstract art, of the conceptual or postmodern or whatever you want to call it. We’re talking Rothko’s umpteen shades of red. We’re talking bananas taped to walls. If I open the metaphorical door, maybe that banana has a cosmic significance that will change my life. Maybe it means someone needed to stash a midday snack and ran out of room in the fridge.

Regardless of where the truth lies, it’s fun to hallucinate, chuckle at your overactive imaginations, or even uncover some effective ways to say much with little. No one agreed that my plain yellow square represented a “Tome of Summoning” particularly well, but no one doubted that two parallel lines and a pair of teardrops conveyed “An Inversion of Time.” I could draft arguments, but none will adequately explain why one idea survived the voyage to other minds and mine didn’t. That’s what can make abstract art infuriating and quasi-mystical: there’s no technique to fall back on and analyze. You get it or you don’t.

Doesn’t stop us from trying to defend our squiggles and make somebody laugh in the process. Whether you’re there to appreciate abstract art or mock it, Starving Artists welcomes you.

Beach Day

I forgot to take pictures. D’oh! This is a photo from the game’s BGG page.

Beach Day, from Cake Pie Games, isn’t aiming for a permanent spot in a collection. In fact, its ideal home seems like a library or an elementary school classroom. That’s a small and unusual target, but it has the potential to hit it.

Its components are sixty or so small, square cards. Twelve of them determine which icons (beachballs, seashells, etc.) and icon arrangements (three waves in a row, pairs of sandcastles, etc.) score points. Four of those scoring cards are used each game.

You draft from the other cards to build your personal beach. On your turn, you can draw two cards from the main deck, playing one and discarding the remainder, or use the top card of one of the two discard piles. If the deck’s down to three cards, that signals the last round.

You lay the cards end to end, covering up any amount of existing beach squares that you want so long as the grid’s neat (as pictured). You could theoretically dump them all atop one another, I suppose. Not many points in that, but the choice has a luxuriousness to it.

A seasoned gamer will tire of this within ten minutes and a young child will move on after three or so plays. Those three plays may suffice, though. Like Get Bit or Incan Gold, it benefits from a tiny table presence and an even tinier ruleset. It’s the rare game which tykes of five or six can teach each other without an adult referee.

Such games have a longevity different from our usual definition. They become many kids’ first step into the hobby, and that’s definitely worthwhile. Daycares and teachers should keep tabs on this one.

Rhyme Scheme

Beach Days is the yin to Rhyme Scheme’s yang. One wants to pass through a lot of young hands in quick succession. The other will sell fewer copies, but its fans will treasure it forever. It depends on how deep your fetish for the English language goes.

Players receive a hand of ten cards, each of which contains four phrases. Simultaneously, they rotate and splay the cards to create poems. Once all our would-be poets are satisfied, they score those poems based on structure and rhyme. Haikus are seven points, simple rhymes are three points, acrostics are a point per word, limericks are fifteen….

Letterpress, Paperback, Codenames, and, to a lesser degree, Scrabble cede ground to non-philologists (“letter lovers”) by adding alternatives to engaging with language: triple word score spaces; deckbuilding; area control. Rhyme Scheme offers no refuge. You tussle with these letters and whip ‘em into shape. That’s the thing and the whole of the thing.

I’m a philologist. I spent twenty minutes constructing verse about a braggart who learns humility. The next person spent the first five minutes on her poem and the next fifteen imagining a noose around my neck. Can I blame her?

In the end, that extra effort satisfied myself, not the scoreboard. Our results sounded roughly beatnik, and that could agitate some folks.

I barely noticed the score. Whoever likes to parse words will leap to it. Designer Billy Grim has made a game (what I can already hear the uncharitable calling “an activity”) for them. I can picture writers playing this over morning coffee to limber up. I can picture myself here.

I can picture Rhyme Scheme in the New York Review of Books’ catalog and, in that company, rating highly. Literary games usually amount to something like “Name That Play” and a pack of flashcards with Shakespeare quotations. Dismal fare. Anything less formal and, well, the triple word scores start creeping in.

The Networks (Reprint)

Fellow tabletop editor Nick Dubs joined me for this one. We played a copy of the 2016 original and gave feedback about the prospect of a reprint.

The Networks has aged about as well as its memes and parodies (cable circa 2001-2012). The stale references I can forgive—I’m a TV critic and stared too deeply into this particular abyss, though I’d argue that calling a show Dextrous ain’t a puzzler. I can’t overlook gameplay that would have felt procedural eight years ago, much less now.

The premise is cute and carries it for a while. You’re the inheritor of a failing network whose old leadership made some…interesting choices. My beginning asset was Name That Stain, airing at 8:00 P.M. It hearkens to the days of Wayne’s World or MST3K, when bottom barrel stations filled the hours with cockamamie crap backed by triple-digit budgets.

Your job is to bring your network into the next era, by which it really means the last, pre-streaming era. You start with cash (Name That Stain was cheap, at least). You need eyeballs and have five years to get them. You have three time slots to fill with hit fantasy series, staff with talent, and subsidize with advertisements.

As rounds progress, the shows and actors enter new seasons and, depending on their species, mature or shrivel. A Morning Show Host paired with reality TV will cultivate a steady, modest following. A Xena-inspired fantasy show, Chainmail Bikini Warrior, performs best at 10 P.M., peaks in viewership during its second season, and craters from the third season onward. A Dashing Star draws big viewership and a fat paycheck until their looks wither in four years, whereupon they’re just drawing the paycheck.

So, you flog the Dashing Hero on Chainmail Bikini Warriors for the two best years of their professional lives. Ax them and use its slot as a revolving door for other short-lived dramas. Meanwhile, your Morning Host will subsist on their cult. Like Dr. Phil, they will molder in their appointed slot until the serpent god Apophis devours the sun god Ra, covering the land in eternal darkness.

There’s some fun both in juggling shows’ lifetimes and reconstructing the mercenary logic of syndication. Unfortunately, it doesn’t develop these elements to the point of leaving a strong impression. It’s window dressing for “buy low, sell high” and some trivial algebra.

Vladimir Suchy’s Last Will presented players with a similar dilemma about aging assets. It made that dilemma harder with a tight action economy and a bigger portfolio to manage. It demanded a sense of timing.

The Networks reduces that dilemma to what you can afford after tallying up revenue and expenses. Rounds last until your money’s gone or you pass, which makes this whole “season” mechanism more low-stakes than it sounds. It tries to inject urgency by awarding a bonus and a higher turn order to those who pass early, but by then it’s too late. The math has turned transparent and dry despite the punchy theme.

The developer concluded the playtest by voicing plans to streamline and simplify the design, especially the turn order. Personally, I don’t think I’ve played a game more deserving of some rough edges and uncertainty. At the moment, it’s too close to the chore of balancing a ledger.

After all, we’re talking about an uncertain business. “Nobody knows anything.”