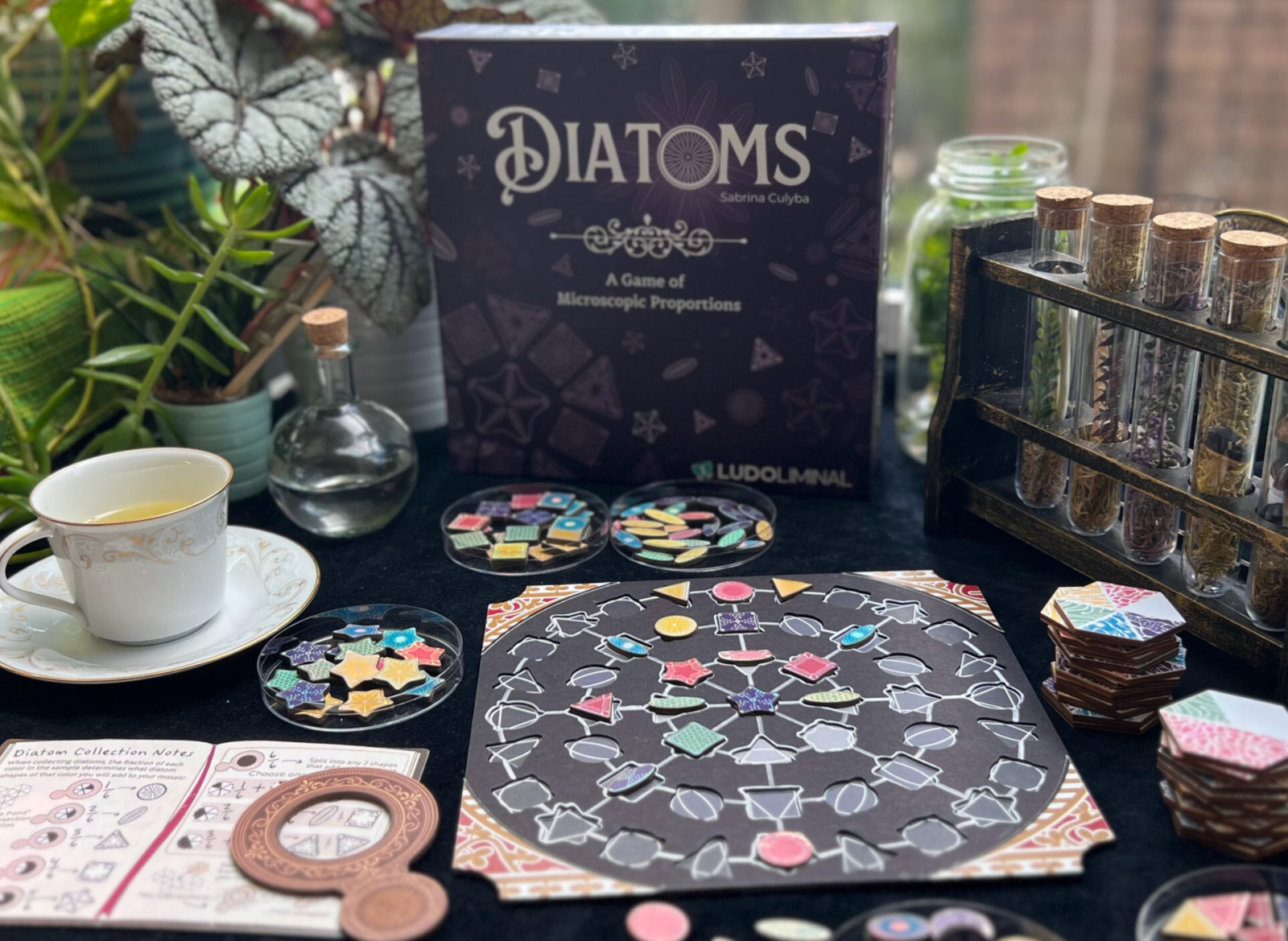

Sometimes a game really starts to come together once the perfect theme is discovered, and for Sabrina Culyba that moment came after a trip to the aquarium. Diatoms may have one of the most intriguing themes we’ve seen in a game as a result, with players collecting microscopic algae tiles and arranging them into beautiful mosaics, hearkening back to a little known practice dating back to the Victorian era. We got a chance to chat with Sabrina about Cardboard Edison winner Diatoms recently:

Mike Dunn: Sabrina give us a little bit of info about yourself and diatoms.

Sabrina Culyba: Well, I’m a game designer. I am based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and I have a very small, let’s call it fledgling publishing company and the first game I’m releasing is Diatoms, and in Diatoms you play as a Victorian naturalists collecting algae from water and then from that algae you gather diatom tiles and arrange them onto microscope slide boards into microscopic mosaics -in the game they’re not microscopic but this is based on a real practice that started in the late 1800s, where people would go out and collect water samples and hunt around under a microscope for the perfect different geometrically shaped diatom and then arrange those diatoms onto microscope slides to really only be seen by a very small number of people. And in the game, it usually takes like hundreds of hours to do that. But in the game, you can do it in 30 to 40 minutes.

Mike: I vaguely recollect hearing about the diatom mosaic art from the Victorian area before this. It’s just like some forgotten memory that I had acquired over the years. So when I was looking at the Kickstarter and looking at the theme, I kind of went down a rabbit hole. And it’s some pretty, pretty amazing stuff.

Sabrina: Yes.

Mike: What inspired you to, like, what came first, the mechanics or the theme, and what inspired you to embrace this theme in this way?

Sabrina: Well, when people play the game, they often talk about the dual puzzle nature of the game. There’s a central puzzle that everybody is playing into with tile placement. That’s the water pond area. And that part is very similar to the very first prototype, which was totally abstract. And I was, I called Fraxagon at the time. Then the mosaic part, which is your personal puzzle that you’re sort of laying out and building up over the course of the game. That came from the theme and that theme emerged, pretty much exactly at the 50% development point for the game because I saw a sign at the Baltimore Aquarium that had a picture of diatoms on it. And that led me down in an internet rabbit hole about diatoms, which were gorgeous, which I had learned about as a word on a page in probably middle school or high school biology class.

Mike: Yeah, and there’s diatomaceous earth which you use to like, you know, get rid of fleas and stuff, right?

Sabrina: Which honestly I never made, I don’t think I’ve ever really made the connection that that’s diatoms, but I never really appreciated how beautiful they were until I saw this sign and I couldn’t get it out of my head. I went home and I was actually at Unpub, which is a board game, unpublished board game events that takes place in Maryland. I was in the Maryland area to go to Unpub and visiting the aquarium with family. And so I was play testing, actually a version of Fraxagon there. And then at night I was Googling about diatoms and thinking, is this, should this be the theme of the game? And when I saw diatom mosaics, I was, I just, I have like a design log and I just wrote in capital letters, DIATOMS. And within like six weeks, two months after that event, I had a version of the game that was themed Diatoms, called Diatoms and visually, aesthetically, it evokes the current game. I went all in.

Mike: Ha ha

Sabrina: And it is one of my goals now that people go down this internet rabbit hole because I think it’s astonishingly wonderful and marvelous and I want everybody to sort of take that journey and see it.

Mike: Yeah, you know what, actually I think I just remembered where I might have heard of it. I spent my senior year of high school in England and we went to the Natural History Museum and I would imagine that some of these slides ended up there. So…

Sabrina: Yes, a good number of these folks who were doing this work were based in the England area.

Mike: Makes sense, makes sense. Very cool. So, yeah, I got to try the game last night on Screentop. And it’s like, if there were other games that you would compare it to, like the first one that kind of came to my mind while I was playing it in terms of arranging the diatoms the little pieces of the diatoms themselves onto the mosaic board was like Azul but four-dimensional or something crazy like that, right? You know whereas Azul is just like a grid basically this was like much more visually interesting and much more brain work because there’s a lot of abstract parts to it that you kind of have to map to kind of game out in your head as you’re placing them.

What games inspired you to make Diatoms?

Sabrina: Well, my goal for designing the game, I actually had a grant to work to create a board game that would be a family-weight, thinking board game that would support math identity. And so I was doing a bunch of different prototypes around different angles on how games can support math identity and what problems in sort of feeling like math is something that’s for you, I would crop up.

And spatial reasoning and fractions were two areas of focus that I was looking at. And so the original prototype kind of came from a game that was like, you were doing a lot of spatial reasoning around fractions and that that’s like, it’s, it’s bud. Uh, and in my dream world, I wanted a game that would have sort of the thinkiness, but also appeal of an Azul for sure. Azul is one of my favorite games. I love how thinky it is. I love how beautiful it is. I love how it’s tied to like a craftsman type theme and so you know I I’m pleased to bits when people compare Diatoms to Azul because I think Azul is a wonderful game that is thinky and chewy but also approachable and family-weight you know you can play it that way so I think Azul can get a little more cutthroat than Diatoms can get if you depending on who you’re playing with I can get a little there’s a lot of theory of my in-depth you can go into Azul try to like block other people. Diatoms, you can kind of do that, but it’s a little more cozy, I think, in the feel. And that’s what, as intentional. The other games that I hadn’t actually played when I was designing Diatoms, but people compare it to, and I own one of them now, Sagrada comes up, which is another craftsman. It’s based on a sort of a craft type of artisan topic, a theme. And then the other one is Calico.

Mike: Oh yeah, yeah.

Sabrina: I think partly because like the heck it’s a puzzly game. It’s got a kind of cozy colors and it has the hex tiles and you’re building like a quilt. So I’ve sort of in my head started imagining like a board game tasting bar of like Azul, Calico, Sagrada and Diatoms. And that to me is, I’m pleased with that comparison. But if you like any of those games, there’s a good chance that you will enjoy Diatoms.

Mike: Well, and now that you think about it does feel like diatoms is kind of like a mix of a little bit of Azul with Calico right? Because you’re building your mosaic but then there’s also the other part of the game where you’re trying how you’re trying to get the pieces by tiling and then and then putting that little microscope not I guess a lens on it which interestingly enough like when I first saw that I thought oh does it have a red piece of plastic on it and there’d be a hidden message thing there. No, no, it actually and I was like, oh that’s nice! That’s a little on the gimmicky side I’ve only seen in a couple of games. I was taken aback by how necessary that was because as I was placing tiles, I was like the part that I was having a little trouble wrapping my head around was like because you’re allocated diatoms according to the intersection point of three different hex tiles. And so when I was placing it, it was a bit of a brain twist to kind of like, you know, game that out and figure out where the best place to put it was. But then I put the lens on it and I was like, oh, it’s completely clear. It’s totally obvious now. So I was really surprised at the utility of that particular feature in the game.

Sabrina: Yeah, it’s interesting to watch people play. So the lens tool serves three purposes. It allows people to see more clearly the sample, especially when they’re starting out. And in that sense, it’s a very utilitarian, like a scaffolding tool. It’s also the current player marker. In one version of the game, everybody had their own lens tool. But as the game evolved, I sort of settled on there’s one, and it’s like the current player has access to that. And so you can use that to pass around because there is some asynchronous to the game where if you’re playing, you gather your diatoms, the next person can start exploring the pond while you’re still thinking about where your diatoms go. And you kind of have to the start of your next turn to make your commitments to where you’re going to place your tiles. And so, uh, there is a little bit of like the game is happening while you’re maybe thinking and that, that lens kind of provides a focus. And then there’s sort of a role play element that people really like about. Like I am peering into the water and scouring around for little pieces of algae, that it’s just fun, you know, and it sort of adds to the immersion of the game. But if you watch people play, the first game people will use it, the second game they might use it, and by the third game, like, they don’t need to use it. They may be, it’s fun to use it, but like they can start to see the sample, and that’s, which delights me because my motivation is kind of like supporting that, that like spatial reasoning, spatial visualization skillset. And so…

Mike: Right.

Sabrina: It’s nice to see that emerge from play.

Mike: Well, and it’s validation that you’re training your players, right? You’re literally… Like, they’re literally internalizing the tools as they’re playing over different sessions. No, I thought it was fascinating the interplay between the hexes and the mosaics. And… It also felt there was a lot of familiarity to it, but there was also a lot of like kind of freshness to how that worked. And yeah, I see what you mean. There’s not as much like player versus player interaction. It’s all about that kind of central hex board. And I imagine there could be some gotcha moments where like one person places a hex and they’re like, no, I was going to do that!

Sabrina: Yes, there’s no hidden information in the game. So you can be sort of checking out what everybody’s looking for and try to combine what you want with maybe placing your tile in an area of the pond that you know would be helpful for someone else. But the game doesn’t super reward that. It’s not a main strategy.

Mike Dunn: So this is your first board game or is it your first board game or is it the first board game for your new company Ludoliminal? Because I know you’ve worked with games for quite a bit of time, both digital and non-digital.

I guess give us a little background on is this your first game or is this just your first like real first game?

Sabrina: Yeah, I mean, I come from video games. That’s like, I worked in video games for 13 years. And video games plus, you know, so VR installation, location-based, in addition to things that would be considered sort of standard video games. So a lot of different experiences. I like, if I’m being true to myself, I think of what I like to do as experience design, and then there’s different mediums and platforms you can use to design an experience.

The, I do have one board game that I published through Peaceable Kingdom with my partner. So we, as a family, designed a family game for very young kids to co-play with adults. It’s a cooperative game. It’s called Yahr Hunt. It was published by Peaceable Kingdom, and it’s currently out of print. It was sold out. It was released at the start of the pandemic. And now I believe it’s basically sold out, and I don’t think that they’re gonna do a rerun print of it. But that was my first experience publishing in the board game world. And this, I hopefully will do more publishing myself through my company. This is the first game that I’m doing the whole process for that.

Mike: You got big plans, big plans! Awesome. Well, you know, right out the gate with a cardboard Edison winner isn’t too shabby.

Sabrina: That was very nice, yes.

Mike: So you come from a video game background, you’ve worked with VR, what made you decide to pull back on the technology aspect of it? Why is Diatoms a board game instead of a video game?

Sabrina: Oh, I don’t, that’s, like I said, I don’t necessarily feel like the platform or the medium is the point when it comes to designing experiences, but probably has a lot to do with becoming a parent. And not that we play a ton of digital games. I love digital games. I have a 10 year old and a two year old now. So we play a lot of different digital games too, but you just sort of appreciating, a growing appreciation for physical board games and that design process and wanted to explore that more.

Mike: Personally, I got burned out on video games and rediscovered tabletop games, which is what got me into gaming in general when I was a kid in the first place. But I think I was fascinated by your background and your decision to go into a more analog world with it. And I think there’s a lot of sharing back and forth between video game design and board game design these days. And I think this, what you’re doing really kind of puts a microscope on it, so to speak.

But what are there any things is there anything specific that you can think of that? you took from your video game Expertise and applied it applied it here?

Sabrina: So I think a lot about the first player experience. And it’s very different designing, tutorialization, scaffolding for a board game than it is for a video game. But a lot of times in… I think it’s hard to not do it at all in video games. Like even when you get like a vertical slice or some kind of alpha version of the game, like you have to kind of explain. And the game can kind of push an explanation onto the players, right? And there’s a whole aspect of game design, which is about that like direct and indirect control for video games of how to tutorialize and tell people how to play. And in board games, there can be a temptation to just. be like, you’re in the room explaining it for a large part of the game design’s life. I operate very strongly around trying to get the game to explain itself much earlier in the process than some people would recommend. It means sometimes sunk cost into it, but that comes from my experience, I think, and my preferences from video games of wanting the game to be able to speak for itself versus having to do a teach. And then that’s how also I prioritize playtesting. I prioritize playtesting with… with families and I do a lot of that play testing 100% cold blind where I’d give them the game and then they play test and I’m not even there and then they report back. Which you know, it comes with costs. It is trade-offs and they’re both different ways of play testing are valuable. But for me, that’s kind of, I think that’s an influence of my time in video games and wanting the game to do more speaking than me as the designer. So that is one thing. I did find.

Mike: Oh nice.

Sabrina: I still find the idea of making complex games much more difficult in board games than in video games because the game has to be run, like the engine is the player’s brains. And so they need to internalize so much to be able to just move the game forward where in video games, players are reacting to what the game is putting out and the game can proactively react to them and present them with new information or prompts or feedback. And that’s hard to pull off in a board game. And so… designing a complex board game with lots of different systems, I think is a like a harder design challenge. Maybe not implementation since it’s paper, but a harder design challenge than potentially in video games.

Mike: Well, and I mean, like a computer isn’t going to screw up the rules, right? Probably, I mean, right, exactly. Right, right. So, yeah, one of the things that we find at Gaming Trend as we review games is that one of the first pain points is, in fact, the rules and…

Sabrina: Probably not. Well, if it does we call it a bug, but you don’t tell the players that they’re the source of a bug

Mike: Sometimes game designers are just too close to their game to write rules. Yes, to write rules for other people. And so…

Sabrina: Always, always.

Mike: …It was it was very like I know I didn’t I didn’t read all the rules, but I did look at the rule book and Just the ux designer in me appreciated How you laid it out and how you explain things? There’s a level of care that you don’t see In probably at least 50 of the games on the market today.

Now let’s talk about your playtesting and your design process real quick. When did you start designing diatoms and what kind of kicked that process off?

Sabrina: It was early summer of 2021. I was doing a bunch of different like prototype ideas, none of which had coalesced into a playable game that I could put in front of naive playtesters. But like, it were kind of interesting around different aspects of math. And it was actually on vacation visiting family and just had, couldn’t get this idea of hexes out of my brain. And it was started doodling in my notebook and then I cut out these little tiles, which look actually look a lot like the current diatom water tiles as it turns out. And I had some vague idea of there was gonna be like food, trays of food that you were trying to get different proportions of meals into a tray, something like that. My little turtleneck tiles were too small. I couldn’t even use them to do like a first play test with family in my, because we were visiting family in Virginia. So I immediately made different tiles that were just color and played that and played that multiple times with family internally.

And then that game was, that was what I was calling Fraxagon. That game was an abstract and continued to evolve with different, with the core puzzle tile placement thing, the same, but what you did with, with what you were gathering with, like when you made your intersections and connected the tiles, what you did with that was different, like changed and evolved. And that’s the part that I kept iterating on. Um, and that fall I started doing blind playtesting with that game. Uh, and, and gut it’s like not, it wasn’t a game that you’d take off the shelf.

Like, it’s like one of the reasons why I never like moved forward with publishing it at that time, or like thought about even doing that, because I knew it didn’t have, it didn’t have the appeal. But when I blind, when I tested it with families who are opting into trying it, at least, and I asked them to play twice, it got really good response from the gameplay. So the mechanics and like how the interest of playing the game, I thought, showed promise. But I didn’t feel like it was something that you’d be like, oh, let’s take this off the box, off the shelf…at the store, because it didn’t have a hook to draw you into some kind of experience. It was purely the mechanics. And like I said, it existed like that for about a year, with me experiencing moments of despair is too strong of a word, but like, is this ever going to go anywhere? I think there’s a good game here, but I don’t know if I can, you know, if it’s going to really bring people in. So then it was the encounter with the sign that kind of led to, oh, this is, now this has something that would not only draw people in, but then there’s gameplay. When you show up and you play, it has the depth and a satisfying thinkiness to it that would keep people. So you can pull people in and keep them. And that I think is like the two halves you need for a successful game on the market.

Mike: You know, it’s really interesting. You’re the second designer that I’ve talked to recently that had the theme kind of present itself and immediately solve several design problems that were inherent in the prototype up to that point. It was Apiary.

Sabrina: Oh yeah. Connie’s game, yeah. Yeah.

Mike Dunn: Yes, Connie Vogelman and Yeah, I interviewed her recently and she was talking about how like she always had the idea of being you know a beehive But you like there were certain aspects that of the gameplay mechanics that were kind of coming up that normal bees would not be able to do and so making it a futuristic space beehive solved all those problems and immediately like kicked up the appeal, the theme appeal so anybody who thinks theme is not important in a board game doesn’t understand How it can just it can just make everything kind of lock in.

Sabrina: Yeah, well, and we talked about that scaffolding and instructional thing too. And I think when there are beautiful moments when your theme. When the player knows the theme and then from that, the player can infer how they think the rules should work and that’s how they really work. That’s gorgeous. Now, now, now the player in some sense is bringing their own internal knowledge to the game and you don’t have to explain that you can confirm it. Like you, it’s not like you can’t don’t have to put it in the rules, but. They have an intuition…

Mike: Yeah.

Sabrina: …that hopefully you can match and that can be lovely.

Mike: Yeah, yeah, so it becomes a collaborative effort with the player Now you said you got a grant to do this, what point in the process did that come into play?

Sabrina: Before I started, I made this, yes, the grant is the source of this game. Oh, and when I say there are moments when I felt like, some like creator despair at, part of it was I had a, you know, I had a grant. I want this game to live up to, you know, a sort of a gesture of faith in my work that comes when you get a grant. So I’ve, I definitely wanted to bring the game into the world to sort of like fulfill. It wasn’t requirement from the grant, but that was definitely the idea that this would lead to a publishable game. Yeah, the grant was through an organization called Karina Initiatives, and they run a fund mostly for video games called the Astra Fund that promotes and supports thinking game developers. It’s a fantastic organization with the fund is fantastic with really amazing creators who are producing great thinking games. And I happened to meet them right when they were starting to figure out what they were going to do as far as the Astra Fund. And so they offered me a fellowship for a grant for a year to support board games, which is not what they normally support. I was a bit, I’m still like an odd duck in their portfolio, but they took a chance and hopefully this game will, you know, it will be a nice additional example of a game that their work helped bring it to the world.

Mike: And then earlier this year you got nominated and then eventually won the Cardboard Edison Award. How did that feel in terms of just, I mean obviously there was some validation that you got out of that. But like just kind of explain how that came about.

Sabrina: Well, so I’m not nominated, you apply. So anybody can apply. So yeah, you apply. You submit, you nominate yourself. I found out about the award the previous year and I just really liked how it was set up where there was emphasis on you get feedback on your game design. And a lot of people from industry judging it. And I’m relatively new to the board game industry community. And so I was kind of like.

Mike: Oh, you apply. Okay, got it.

Sabrina: I also appreciated all the work that Cardboard Edison puts out in terms of providing resources for creators. And so I became a patron of theirs, I know, through their things so you could get their backlog of information about game design tips and stuff like that. And so I was aware of the word, the process that they do and all of the resources they provide to game creators. And I thought it’d be nice one day to submit a game to that. Meanwhile I was working on Fraxagon, which should become Diatom’s. And I took Diatom’s.

in its pretty close to its current form to Packs Unplugged in December of 2021. It had really good reception there. I was in love with, like, the theme of the game, and I thought it was a pretty decent game. So I said, well, the deadline’s in January. I’ll submit this game. And to submit, you have to make a video, a two to five minute video and submit the rules. And then you have to be prepared, because if they are like, we like your game enough, you have to send them a prototype. So you have to have like

Mike: Right.

Sabrina: You have to have a completed game, although it doesn’t have to be production quality. So I submitted a video and the rule said, and my main, at that time, I thought maybe this could be a game I could take to crowdfunding because that to me felt like the only way I could be commercially successful as a publisher first time, because it’d be hard to get my game into retail stores or stores just having a catalog of one. I think usually people are like distributors, et cetera. They’re looking for more, you’d have more games under your belt. And so I thought, I was thinking crowdfunding might be the way to do the first game that I put out there, although in my world of advice to myself, it was not, it was a card and dice game I should do first, you know, something a lot easier to produce. Um, but I was starting to feel like diatoms might do well in crowdfunding that it might, it might pull in people because of its really cool theme and beautiful look and really thinky style that might be a really good fit for the crowdfunding space.

So my hope was if I could become a finalist, you get listed on the page for forever. And that would be, since I had like no following, was a company no one had heard of, that would be a very small way to, you know, to just kind of boost visibility for the game. And then I knew I’d get feedback from, no matter what happened, from industry folks who played. And I thought that would be really useful feedback for me. So that’s why I did it. And I was a finalist, so I sent a copy of the game in, and then…

I wasn’t like entering to win first place. So I was really surprised and pleased and it made me feel really good about the game in terms of like choosing it to bring to market because a lot of people had played it who I had no relationship with, who were from industry, who play a ton of games.

Mike: Right.

Sabrina: And they thought it was a great, innovative, interesting, compelling game design. And so that said, to me, this game could have legs as a game out there and that it deserved to be out there. And that made me feel more confident about moving forward.

Mike: What made you choose to go the crowdfunding route instead of say you know finding someone to publish it selling the idea to a larger company?

Sabrina: Well, it’s kind of like my decision to want to publish a game came before deciding that it’d be items that I would publish first. And I have other designs that I’d like to publish. Then some of them I’ve pitched to companies too. And I’ve done the pitching thing and you know, it’s part of it is goes, goes back to like what I really enjoy, which is the experience design. A lot of times with board game design, when you pitch to publishers, you… they take the mechanics and they put on all the, it’s like the other stuff isn’t part of what you get to design. Like the theme, the visuals, the components, how the box looks, how the box opens, what’s the rule book, all of that stuff you don’t get to be designer for most of the time. Someone else does that, it gets another team that works on that, which is fine. They do, there are people who are really, people do a great job with that, but I like that stuff. I wanted to do more of that stuff, you know? So I thought the only way I’m really gonna get to do that.

Mike: And you’ve kind of done that stuff already on the video game side, right? Like you’ve already taken games from Concept to publish before, so yeah. Yeah, with the team, but yeah. Excellent, excellent. So it looks like your Kickstarter is about almost halfway through time-wise. Yeah. And…

Sabrina: With a team, of course, right, but yes.

Time-wise, yes. I think we have two weeks, a little over two weeks left.

Mike: And you’ve made your goal. Now I imagine once the crowdfund is completed and you’ve made your game and you’ve gotten it out to backers that…

Sabrina: Yes. I will be making this game for sure now. I have the funds to print the game.

Mike: …you’ll be looking to possibly get other companies involved in terms of distribution and stuff like that. How far ahead have you been thinking of that? Has anyone come knocking?

Sabrina: I’ve definitely had conversations. I, there’s, you know, when you do the publishing, there’s so much that comes into it. And some of it I’m, you know, I’m all done doing all that stuff. I’m doing for the first time. So I come from game design and game development. That’s super familiar, but manufacturer shipping, uh, distribution, fulfillment, retail, all that stuff is new for me. And I’m learning a lot. Uh, there are some aspects of it that I find less enjoyable and that it would be more intimidating to scale. Being present at all the shows with a booth, that’s a nice, great experience for people to come and see the game. There’s a huge scaling issue with that when you’re a solo entrepreneur. Or even if I were to scale up a little bit, it would still be difficult to be present. So I have been thinking about how can I build a partnership that would make it more possible for the game to be at these places, these specific events be available in more spaces around the world. So we’ll see what happens with where that goes. Yeah, I can, as a tiny company, do it all myself. And I’m definitely hoping to forge multiple partnerships to make things happen for this game and future games.

Mike: And you said you’re going to be at Pax Unplugged this year. I guess you’re right down that you’re right down the road from it, right? You’re in the same state. Yeah. Well, it’s a little further away.

Sabrina: I will. Actually, I’m in Pittsburgh. It’s a little further away, but you know what? I went last year for the first time, really enjoyed it. I met a lot of great people. I had a great time in the Unpub Room, which I recommend to anybody who’s working on board game designs, fabulous people there, and really enjoyable play testing. So I am definitely gonna do it. I’m not gonna have a booth or anything, but I will have at least one copy of Diatoms with me. So we won’t be, the schedule for Diatoms is the print will be starting at the end of the year and then will ship by July of 2024. So we’ll be far out from getting boxes and hands of backers at Packs Unplugged, but I will be there with the game and checking other people’s games and yeah.

Mike: I hope that you can set aside some time for us. I’d love to get a play of the game, the physical game.

Sabrina: Yeah, that would be fantastic. Yeah, the screentop version is good, but the physical version is, the tiles are shiny and very satisfying and they slot really nicely into the board. There is something about opening the box and playing with the pieces that you can’t get.

Mike: You just can’t beat the tactile nature of a physical game.

All right, I’m going to leave with two more questions. The first question is, what games are you currently playing right now that you’re really into?

Sabrina: Okay, I just finished It Takes Two in the video game world, which I’m kind of late to the party on, but I had a really great time playing that with my 10 year old. And I haven’t started a new video game as of yet. And I am about to play, I just got Dorfromantik and Fit to Print, which I was a backer for. So those are two games that I’ve really been looking for. -Dorfromantik, the board game, not the digital version. So I’m hoping to play those very soon. It was, and when you talked about like the interplay between video games and board games and how the lines are blurring, I think that’s just like a beautiful example, right? I mean, video game, turn board game, one game of, you know, gateway game of the year, biggest, most prestigious award in board games like that’s.

Mike Dunn: That was a spiel winner, wasn’t it? Yeah.

Sabrina: I think that’s just a signpost of how there’s interesting interplay happening.

Mike Dunn: Totally, totally. And then the other question is, I’m going to wager that you have other games that you’re working on, that are in the works. Is there anything you can tease us with? I know you’re still in the middle of this Kickstarter and you’re trying to stay focused, but a good game designer always has more in the pipeline…

Sabrina: Oh yeah, I have like half a dozen games that I think maybe someday could, I’ve reached the point where I feel like maybe someday they can make it. The game I was planning on publishing first before Diatom is called Unicorn Clinic. It’s a game where you are cooperating, it’s meant to be played cooperatively with kids like the six, seven age range and adults where you’re treating sick unicorns. It just didn’t quite, hasn’t quite found itself yet. So I haven’t, I’ve pushed off publishing that, but I’m excited to release that. And then I have two others, one that I’ve pitched around and gotten rejected, but it has like amazing table presence is really fun. Every time I play test that people are like, can I buy this now? So I am now thinking maybe I’ll, if Diatom’s goes well, maybe I’ll publish that one myself. It’s called Earthquake Escape. It actually won the Haba USA Family Game Design Contest in 2021. Like the same time I was starting working on Fraxagon, we submitted this game design to Haba and won that. You know, that’s a very tiny little contest that actually I don’t think they’re running anymore. But, but, and then they then they said no to publishing it. Yes, they’re like since then some stuff has happened, but they rejected it before that happened like they I said once you win that they look at it for publishing and they decided not to not to move forward and I’ve pitched to other places and haven’t found a biter but I really like it and think it’s and that’s another kid adult cooperative which is a large portion of what I’d typically design is yet younger than diatoms with adults.

Mike Dunn: Well, excellent. Well, thanks, Sabrina. We will definitely see you at Packs Unplugged. And yeah, out there, go try the game. Go back it. It looks great. It plays great. And I think it’s going to be a hit. So yeah, thanks again, Sabrina.

Sabrina: Thank you.

You can back Diatoms right now on Kickstarter