The titles Root, Oath, Pax Pamir, Arcs, and John Company will most likely ring a bell for regular members of the tabletop community. Like any collaborative project, their success can’t be laid solely at the feet of any one person, but they have a common thread: their designer, Cole Wehrle. Cole’s work has won praise for its ability to balance heavy subject matter, insight into complex subjects, and a surprisingly broad appeal (especially given the density of those subjects).

As the old saw goes, nothing is new under the sun. Cole is not the first to approach, in game form, Afghanistan’s turbulent past, the East India Company, or fuzzy woodland kingdoms, but he has extended to them a unique wit and sensitivity. Today, I hope to explore that quality, as well as shine a light on some of his latest projects.

So, Cole, in the past you’ve likened designing a game to constructing an argument. Can you briefly elaborate on what this looks like to you when designing?

I think when you’re building a game, it’s not enough to have a setting in mind or even a mechanical innovation. Maybe it’s enough for some people, but it’s never been enough for me. I always feel like I have to have some idea, some argument, some model that I’m trying to communicate. I think all games are, in a sense, arguments about the past in the same way that stories can also be arguments about a particular time or moment. And once I have that central argument, it informs almost everything about the game. It informs the number of players it takes, how long the game might last, the aesthetic strategy of the design, and the relationships between the players.

But I also know that whatever arguments, whatever ideas I might have about a particular time, there are other arguments that can be made, too. I don’t get to control every little voice or element of my game any more than I can separate myself from my own historical context.

That’s a slightly meandering answer, but the main thing is when you’re—and I think this really comes to me through my experience in historical games—when you set out to make a game on a well-known battle, you’re not just modeling that battle. You’re presenting an argument of how the battle should be modeled, and that logic can apply to any thematic setting.

To cite a famous instance: the Campaign for North Africa [by Richard Berg]. An oft-given example of baroque design is the use of pasta when tracking Italian armies and their march. But that’s basically promoting the idea that an army marches on its stomach, right?

Right.

Speaking as a fan of philosophy, poetry, and, in particular, Johann Sebastian Bach’s music, I can’t help but recognize parallels between games as arguments and structural concepts like fugues, hegelian dialectic, and villanelles, where the structure provides constraints to push against. These are forms which stress the constant return to a thesis, a rebuttal called an antithesis, variations on both the thesis and antithesis, and then a resolution, a synthesis. Do you feel like that’s an accurate comparison, or am I stretching the point?

Well, games have their own peculiarities. One thing they’re bad at, I think, is the kind of precision and causality presented in written narratives. One nice thing about writing an article, for instance, is that words have a way of going in a certain order. When you’re working in that kind of linear form, you can’t help but either make explicit causation or implicit causation.

Games aren’t like that. There are systems at work. You can have pushes and pulls and different kinds of hydraulic systems, but if you’re trying to model historical causality, things can get murky pretty fast. The classic example of this would be something like a card-driven war game, where players are pulling cards out of a deck. In the case of Tory Brown’s recent and brilliant game on women’s right to vote in the United States, sometimes Reconstruction (1865) happens before the Civil War (1861). Now, that’s obviously laughable, but in the context of the game and its framework, the order in which those things happen doesn’t really matter too much. It’s okay to juggle them up.

To me, I think that the best game design, both the best design work I’ve done and the best design work I see in others’ games, is deeply sensitive to the fact that we’re doing games on the tabletop. It seems like it’s almost nonsensical to even say this, but a lot of people who work in tabletop games have aspirations to do video game design work, and they’re huge fans of video games.

One of the most common sets of tropes I see (I always pick on this genre, so I feel a little bad) come from Civilization. You see the mark of Sid Meier’s Civilization constantly, perhaps most notably in games like Clash of Cultures. Or if you’re playing something like Eclipse, obviously the designers loved Masters of Orion. You can see the fingerprints all over it.

The problem is that a tabletop board game can’t recapture sitting in your parent’s basement playing Civ II when you were fourteen or fifteen years old…. There are different formal elements. And so I try to remember constantly that I’m working on a little stage that’s in people’s basements and kitchens and cafes. There are certain expectations when it comes to the form of play that I, as a designer, have to engage with because if I don’t engage with them, they are going to be engaging with me.

“I try to remember constantly that I’m working on a little stage….”

This is why, for instance, Arcs, my recent science fiction game, is designed around a trick-taking framework. Someone asked me, “Are you doing that because trick-taking games are popular?” I said, “No, I’m doing it because trick-taking games are digestible.” They offer very cinematic temporality. You know, if you’re playing a trick-taking game, the question of who has the initiative and who has the spotlight is constantly shifting in the game. The value of my hands, the kind of difficulty that I, as the protagonist in the state of play, have to face is subject to my own opportunities and the opportunities the game’s being presented by other players.

So there’s an uncertainty, and I find that texture of uncertainty to be extremely narratively resonant. It’s why if you look at novels and poetry from the 18th and 19th century, you see a lot of trick-taking language used as metaphor in those books. It’s because it’s a robust, expressive ludic language. [I will cop to calling trick-taking “inflexible” in the past. I look forward to revisiting that opinion with Arcs in the future. Ed.]

And given the prevalence of coffeehouses as the locus for civic debate at the time, it would have been something with which everyone had ready familiarity.

I wrote a little essay on trick-taking games that touched on that a bit. It’s interesting how it tends to provide its own narrative because you’re charting out—It’s about programming your own hand against that of other players, and oftentimes the amount of variance in there means that you’re always going to be thrown off-course. So I can see the drama of it.

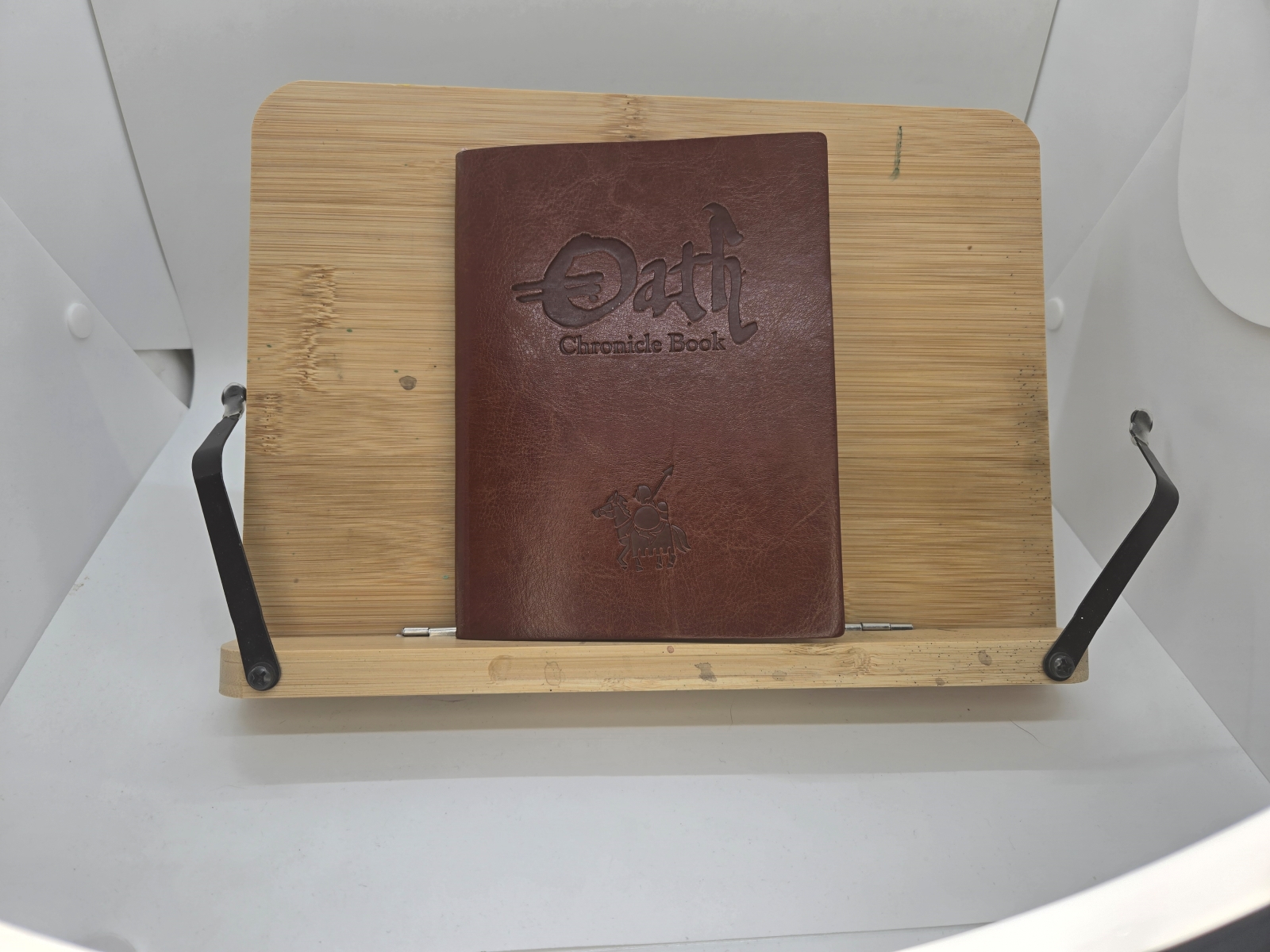

Speaking of drama, you’re currently developing an expansion to Oath, which is one of my favorite games, and you’ve elaborated on its identity in many delightful, well-written designer diaries. I don’t want to completely rehash them here, but could you briefly reiterate [Oath’s central thesis in a topic statement?

Sure.

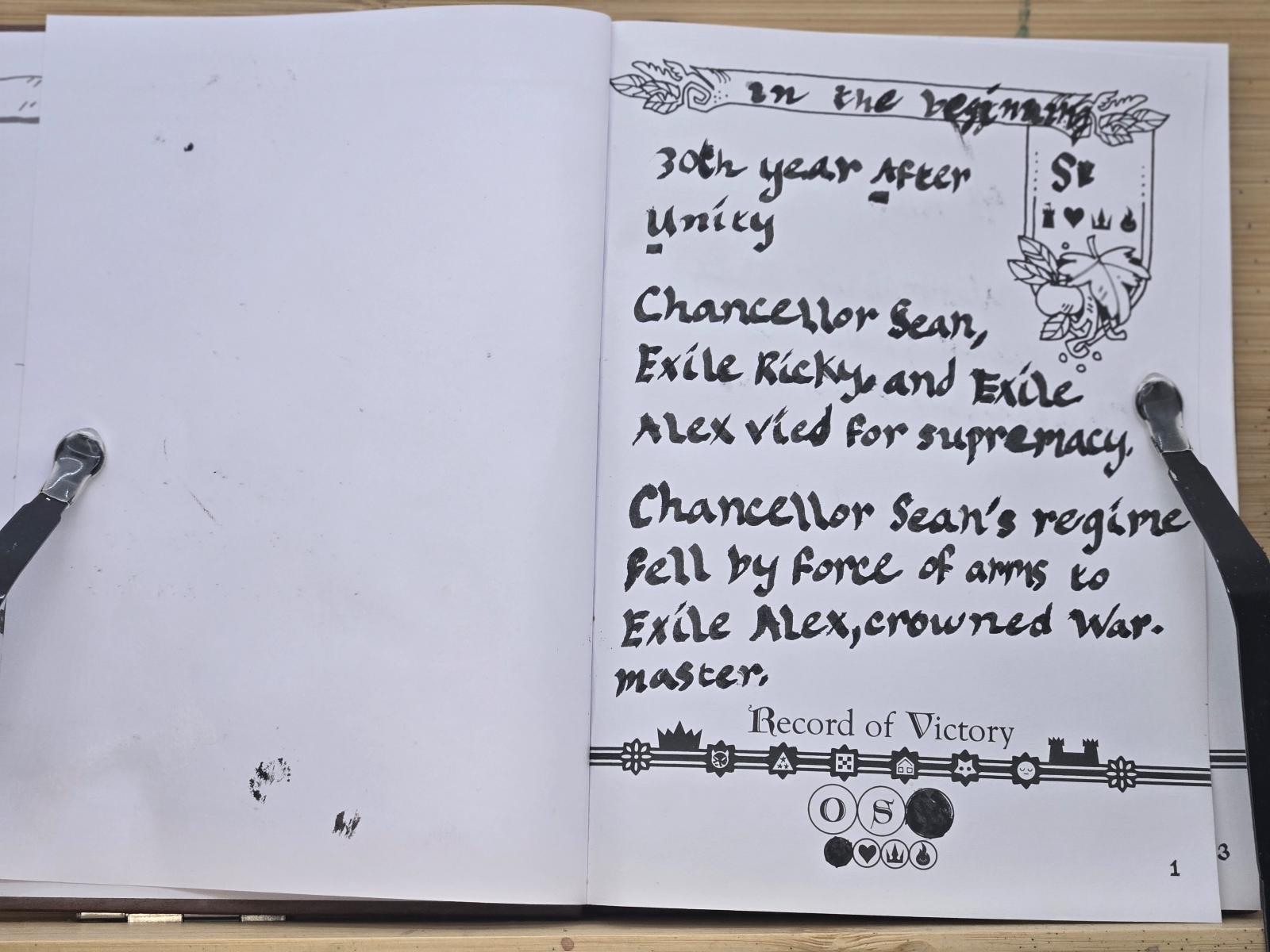

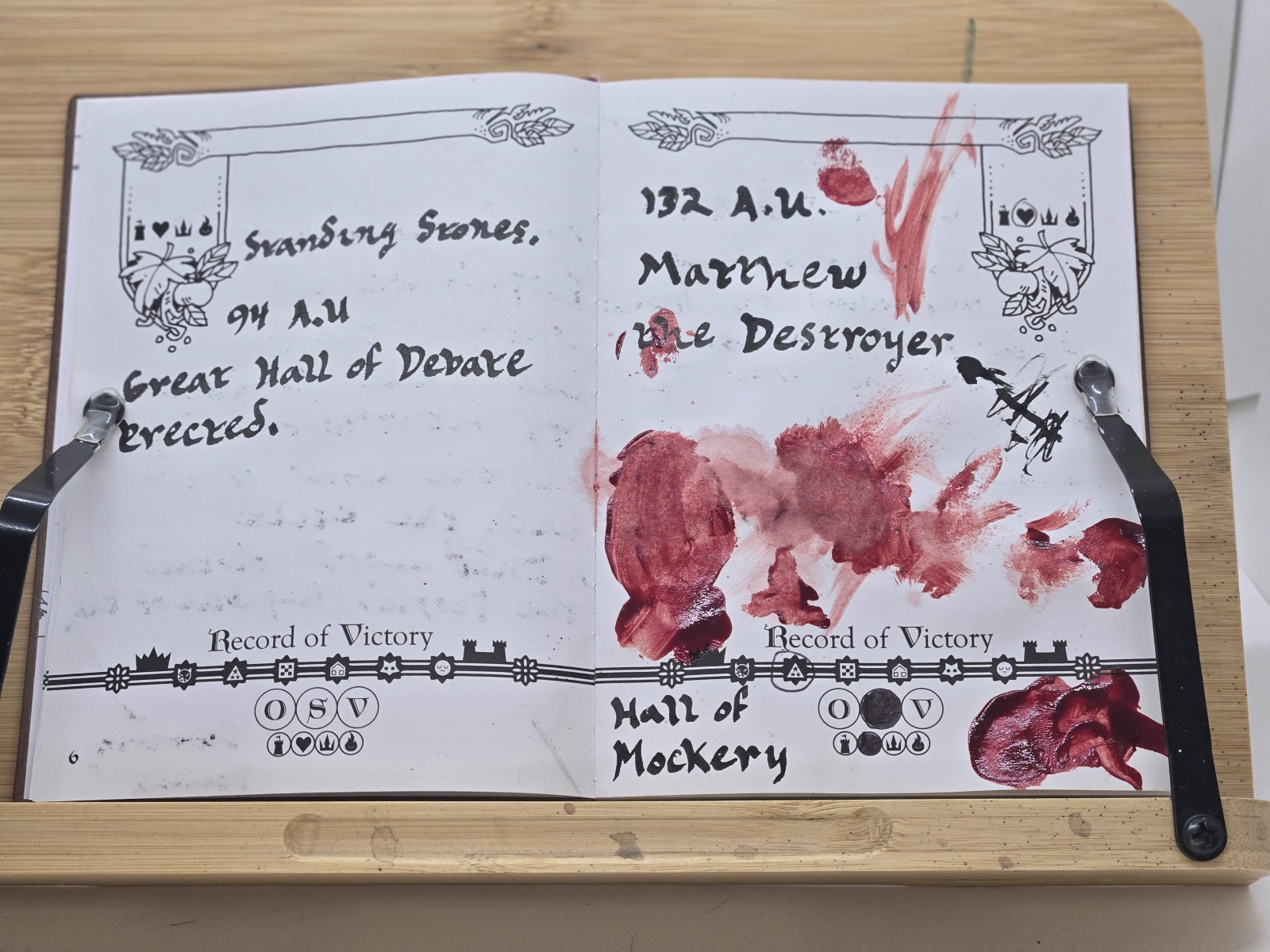

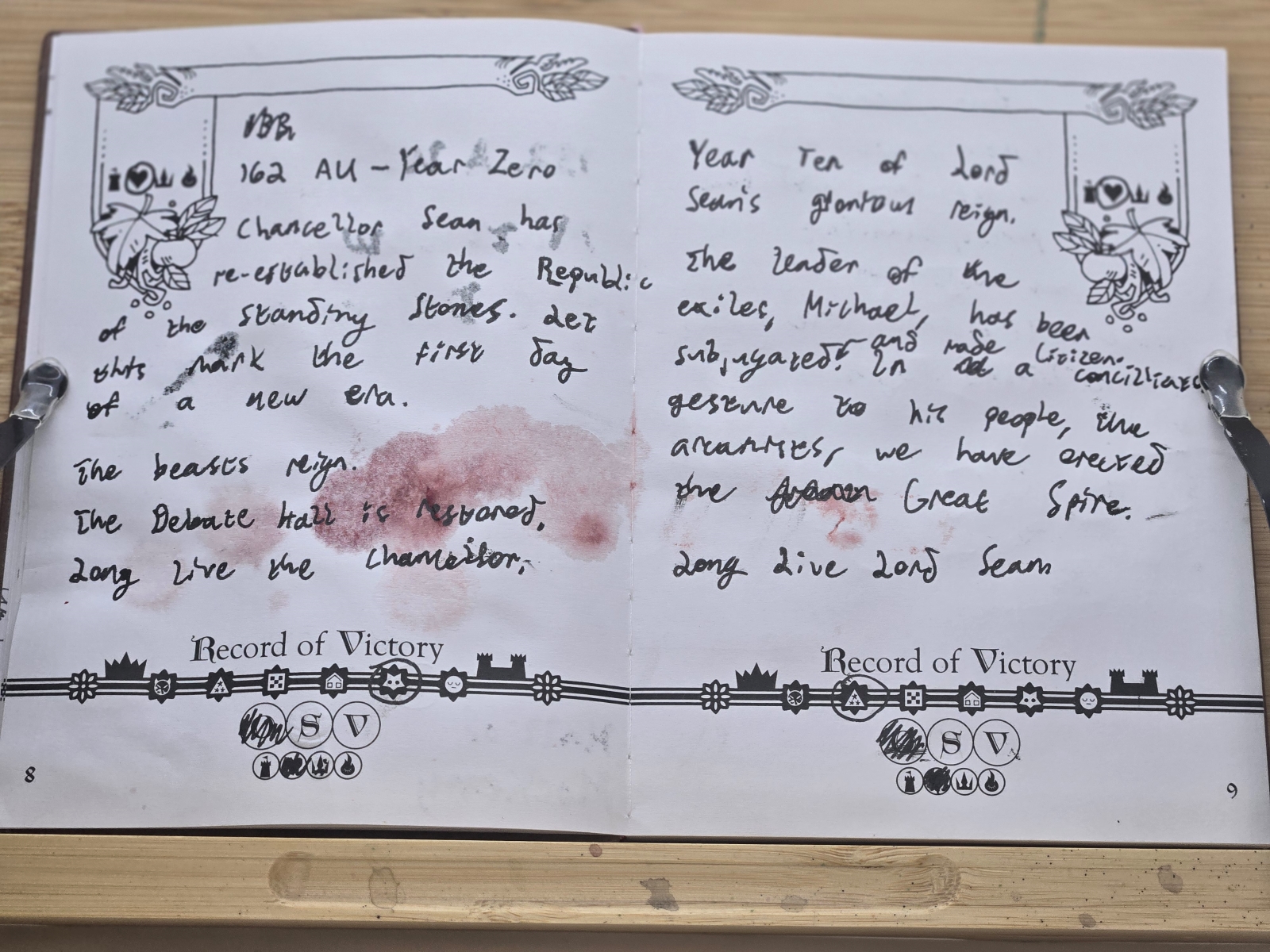

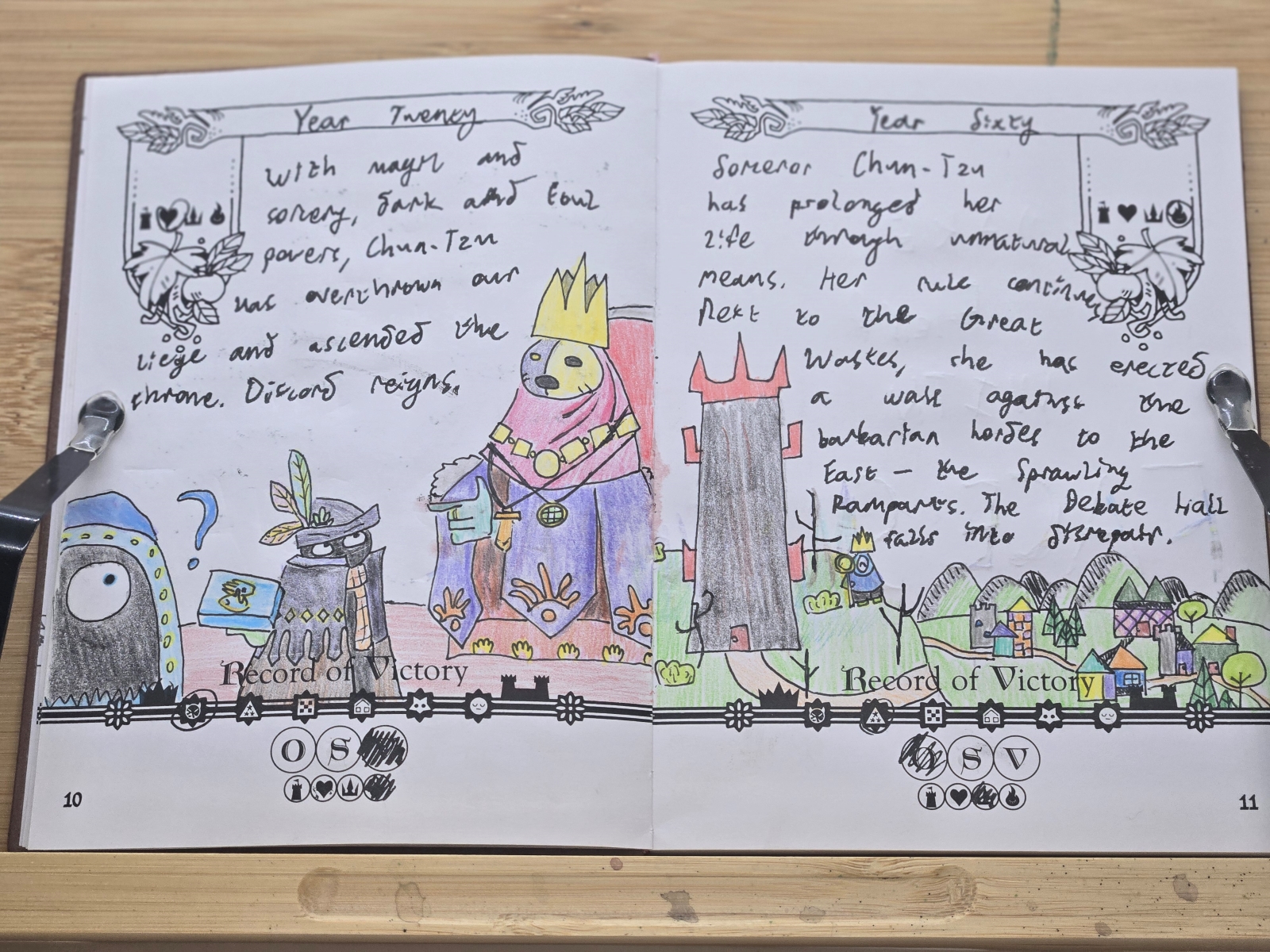

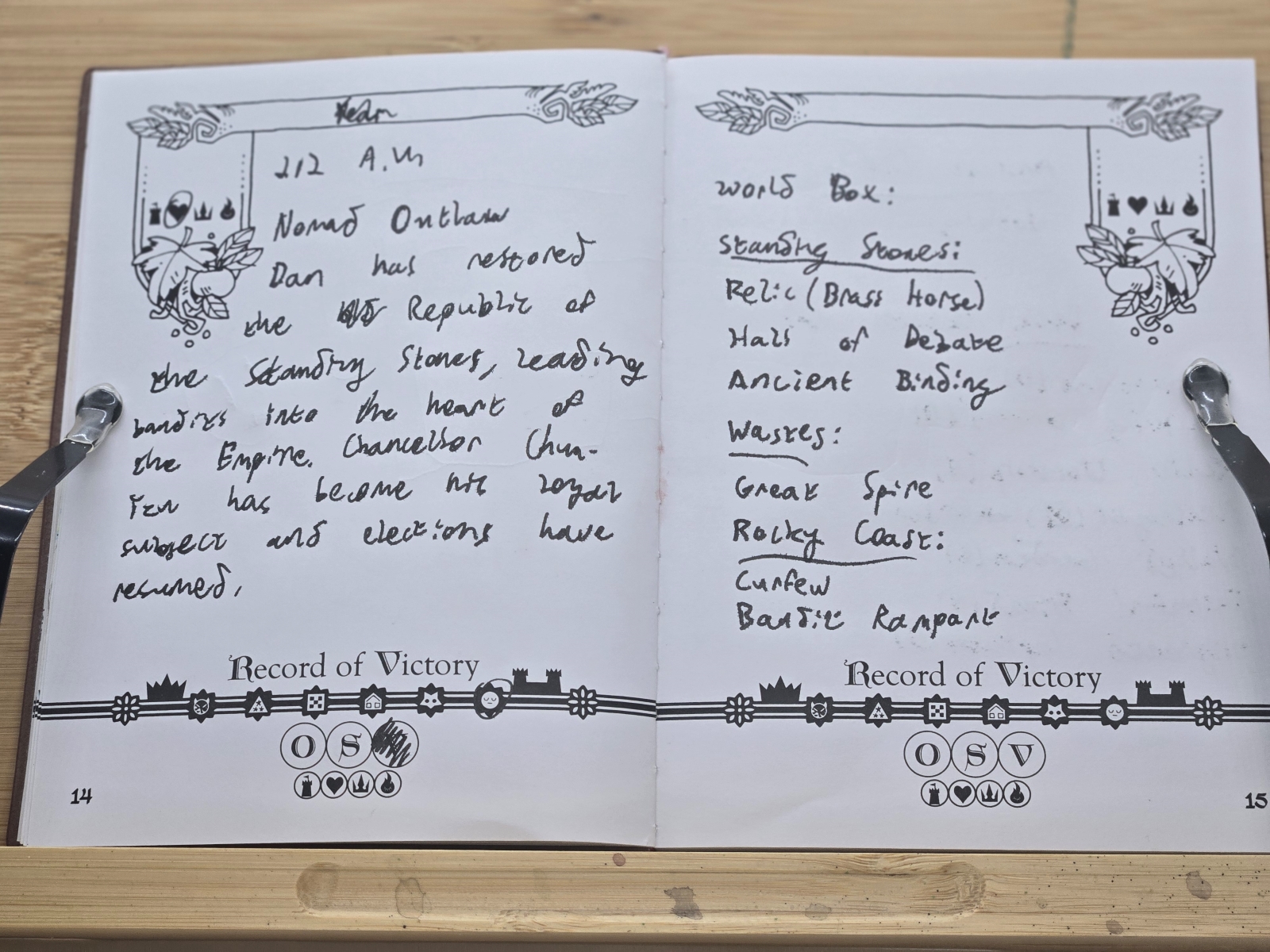

Oath was built on a really simple premise, which was that we wanted to design a game that could remember how it was played. What we didn’t know when we were working on Oath was who this game was for. So we knew that we could probably build a game that could remember how it was played in some way, but we didn’t know what kind of player would like that game.

And we thought, Oh well, maybe some players are going to be playing this casually, just a drop in, drop out, pick-me-up game. There are certainly lots of players who play Oath like that. And, in fact, that’s mostly the way that I play Oath.

But the audience that has emerged for Oath over the last few years has been an audience that has been really interested in telling these kinds of generational stories. They’re compelled by the notion that they’re going to play the game five or ten times in a year. They’re going to wait a couple years, they’re going to take the box back out, and then they’re going to continue that chronicle and allow the game to develop a deep history.

Now, the problem with that is that Oath doesn’t offer players quite as many tools to do that kind of storytelling as we would like. And what we’d like to do with the Oath expansion New Foundations is basically broaden the expressive range of the Chronicle. I want to give players…a wider set of tools for transforming their own game.

Now, how they transform that game is going to be up to them. If they want to steer the game towards a higher complexity or more of a negotiation game, they’re going to be able to do that. If they want to steer the game more towards a wargame, they’re going to be able to do that.

This framework was really made possible through working on Arcs. [With Arcs,] we had just finished a really large game design that is almost designed to be modded in the course of play. The game is designed to grow and change as it’s being played. We learned a lot in the process of working on it that we were able to directly apply to Oath, and that formed the foundation of Oath’s expansion.

Regarding “a game that remembers,” I’m going to provide and ask for a little contrast with legacy games, which was Rob Daviau’s run at the concept. Daviau worked for Hasbro, and during a brainstorming session on a version of Clue [Cluedo outside the U.S. Ed.], Daviau joked (to paraphrase), “Why do the same guests go to the same mansion every time, why do they always experience a murder, and why do they never seem to learn?” His whole concept is about a game that doesn’t “reset to zero” every time you play it.

I feel like Oath is different not just in how endless it is, but what it says about historiography. Maybe “historiography” is too broad a term for what you’re saying because, to follow your point from earlier, games are all about the past: our own time affects what we play in.

Right.

It’s a perspective I’ve encountered before. I come from an archaeology background. Post-processual archaeology describes an entire movement of thought repudiating the empiricism of processual archaeology in the 1970s, of a data-first and objectivity-driven approach to looking at human evidence. It tried to prove that stuff wasn’t necessarily objective at all. No matter how scientific, archaeology inherently has cracks through which deconstructionist—through which assumptions about time or the way cultures work could slip.

With that perspective in mind, how do you see it in comparison to Daviau’s idea of a game that remembers, that has a history? How do you view it as an arguer and historian?

Well, I think the core difference…. I think Daviau is much more of a literalist than I am.

Because he’s right, of course, that Clue doesn’t remember, and then it makes sense that he would go on to work on legacy games where the games have a kind of memory function built in. I mean, the thing that I disagree with most stridently in terms of design practice is that I don’t want to be the story function in my games. I want the players to generate the stories. I have a much more player-centered narrative focus.

I think both of us are player-centered designers. Of course, you can’t help but be so. But I think Rob is interested in making Clue present a story so that the characters within Clue will learn and can experience all of those narrative branches.

But I don’t think it matters that the same people within the game keep showing up to the same house and same dinner party in Clue because the players themselves remember when they play Clue—they come to the party having a better sense of the social relationships between all the cast of characters, which of course are the people in your home. This is the metagame, right? When you play a game of Risk or Game of Thrones and you saw your kid sister betray you last game, you know that happened.

“I think Daviau is more of a literalist than I am.”

It’s interesting that you mention that story about Daviau. I’ve never heard that anecdote. It contrasts sharply with the origins of Oath:

I was listening to people talk about games of Root and they were describing them on a generational scale. They said, “Oh, you figured out this thing and won four games in a row for the Marquis de Cat faction, and then I finally dethroned you.”

And I thought, Well, Root doesn’t do that. Root isn’t interested in that kind of dynastic struggle, really, and yet the players are bringing it through. So how do you make a design that’s open to metagaming in productive ways? So we’re kind of hitting the same question Daviau considered from the opposite direction.

Also, another point of contrast with Daviau (I think he’s a brilliant designer, by the way) is that he knows all the clever things his game can do because he’s constructed the whole narrative of the game first and then the players play within it. My approach is a lot more like the designer ethos you see in roguelikes where the designer provides you with a set of tools and then asks you to use them in ways that surprise me constantly.

The subversive nature of play.

Yeah, yeah. It’s sandboxy, a little bit more open, and it empowers the player.

To me, play trafficks in metaphor and allegory and improvisation. That’s true of tag and that’s true of the most complex wargame out there. There are always moments when things go bad and you have to navigate them.

Or points where you’re deliberately starting from an unfair position.

Warhammer is pretty much a traffic jam in that sense. People buy parts for their faction to try and create a sense of unfairness, or deliberately set up scenarios that are weighted games as opposed to balanced matches. They even label them as “narrative games.”

Well, I’ll go a little further and say that this isn’t all good. From the way we’re talking about it, it’s like, “Why doesn’t everyone design like this?” And I’ll tell you why: when things go sideways, someone might not have a good time.

You can trip while playing tag and sprain your ankle. That’s a bad experience, might be a great memory, and might have been good in the context of that game. It’s not going t”Theo stop you from playing tag once you’ve gotten better. But if I’m trying to optimize, say, ten or fifteen minutes spent on a “match” of tag, then I’m going to smooth and even the grass as much as possible.

In a sense, that points to a larger truth about what we call drama. What do we get from elaborate constructions about reality where we have people pretend to be other people (games, included) and speak lines as if they’re in the moment, in real time? (Aristotle called this mimesis, or “mimicry.”) Composing reality in an ordered way, removing the random stuff, is part of the relief of drama.

But because they’re improvisational, games are almost forced to put them back in.

To return to your point about Daviau and his narratives, he almost seems to be using first- and third-person language, wherein you inhabit a constructed character and you go through a scripted play.

Oath and the type of gameplay you’re describing seems more like it’s second-person. You know, the stuff of choose-your-own-adventure books or text adventures.

Right.

And it feels like in general (at least in this part of the globe), we don’t have a lot of affection or knowledge of second-person narratives. When I was growing up and learning the trade of writing from my professors, they said, “Second-person is bad because you don’t want to tell the reader what to do or tell them an experience they don’t have; it creates disconnection.”

In games, second-person is almost inevitable. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it does make sense. I mean, there’s a technical way to approach this subject. When it comes to the actual writing of rules, the second-person address gives you a lot of clarity and grounding.

And it can have problems, too! But if I have to have, like, a grounds of address in any of my design work, give me the “you” plural [For which English still has only y’all. Alas. Ed.]. But I try not to be prescriptive to the players at all. In fact, as I’ve helped more groups and helped younger designers and thought about my work in a broader context, the most common trend I see is that designers and players always think they understand an objective truth or reality about games. And it’s just…it’s just not the case.

The most common example of this is players who find a game to be too complex or not complex enough.

Yeah.

And they’re failing to imagine the wide existence that a game will have or—

Their cultural assumptions about how games should be constructed, as a post-processualist would say.

And I’m certainly guilty of that, too. There’s no way around it. But I often tell people, when they ask about my experience in graduate school and university, that the most useful thing I got out of it—the thing that makes me happy to pay my student loans every month—was an understanding of the shape of my own ignorance.

Not that I can understand the full shape of it…because you can’t! But I do feel like I have a good handle on the things that I don’t know.

So, I don’t know…. There are different ways to think about your footing with respect to the player. I guess I’ve kinda stumbled into being an advocate for reader-response theory because I do think the fundamental meaning of the work is negotiated between the team that creates the work and players.

The work exists within that overlap, so, as a designer, this means I need to make games that are playable, that people actually play. If no one’s playing the games, then I’m not actually making them.

It becomes a dead thing.

And I admire a lot of designers who do more “art pieces” as design. I think polemical designs are interesting. But to me, if a game cannot withstand, I don’t know, thirty games of critical play, a competitive scene, or an engaging audience, then I failed, because the game is only alive if it’s getting played.

And so I could make the most interesting, articulate object imaginable and everybody can say, “Oh, that’s interesting” or “That hits” or “That has an emotional impact.” If they walk along, then I have screwed up because I’m trying to make objects of play—it is in play that they live.

It’s interesting you mention art piece games because I caught mild flak, actually, for writing about Train a while back. For anybody who doesn’t know, Train is basically a Parker Brothers game.

I mean… I hate to use that term because it’s considered much more derogatory [than I would like, but it really does have rules that I would expect out of a classic Parker Brothers design. You pack trains by rolling dice and unpack opponents’ trains with take-that cards, then you learn in the last round of the game that the trains are headed to Auschwitz.

“If no one’s playing the games, then I’m not actually making them.”

It was trying to talk about complicity in the Holocaust and so forth, but my key issue with it was that it didn’t seem to be interested in any of the developments of games as a living thing. And recently I had a discussion with a new designer and creative team with the same mindset. He, too, didn’t think he had to play games that came out recently or stay up-to-date.

And I know that, at first blush, that seems absurd to most hobby people. It’s like a chef that doesn’t taste modern food. But let’s examine it from a neutral point of view and ask why you should want to keep in touch.

Well, there’s a conversation happening right now: how do games speak? What do we do when we play? And the way one participates in the conversation is by making games.

I’m the sort of person who prefers to listen before I talk. In school, I was always quiet for the first few weeks of a class because I wanted to know what people were talking about…the general shape of the conversation. And then once I had it, once I knew what that shape was, I felt comfortable saying something.

Games are the same way. As a designer, if I were not playing current games but still publishing, it would feel a little selfish to me. It would feel a little obnoxious. In the same way that a person who is not in a conversation walks into—you know, someone shows up to the—

Town hall meeting.

They’ve never been there before and they just start shouting things and leave. And I’m like, “Cool.” Maybe they even made some interesting points. I will allow the fact that they might be able to make interesting points, but I’m interested in the conversation and not just an individual utterance.

This is the place where folks disagree, and I also think there’s an aesthetic aspect here. Train is a good example. I also don’t think it is good or interesting. I think if Train were a short story, no reputable literary magazine would have published it because it has such a cheap trick and I think it’s poorly executed.

The novelty is so striking, and that accounts for the fact that people still talk about it. And that’s fine. I don’t want to diminish the innovation it presents. But to me, there isn’t a deeper conversation about Train.

I suppose that novelty is a factor in any medium. I believe there was a man in Texas [ Wrong! It was Cape Cod! Ed.] who was rewriting classic operas to give them happy endings. Presumably, he had an audience pay for tickets.

So I don’t think that novelty is inherently objectionable, but it has limitations when you’re trying to talk about it because the discussion around it becomes more important; it has almost nothing to do with what you just presented. You might as well have provided a synopsis.

But I do see how other people can say, “Well, why not? Why not do it for the conversation?”

I mean, that’s the value of Train. Someone’s using a game to tell a kind of stilted short story. Fine. Great. Good. Excellent. It goes in the history books. That’s fine, but I don’t think it’s actually pushing the conversation forward in really interesting ways. And it doesn’t have to, but then we just move on.

Well, there’s one thing about Train that I’ll say that is a little—I mean, this is maybe mean-spirited, but I don’t intend for it to be. The people who are interested in play and games and the limits of the form—they don’t talk about Train. The people who sometimes come in from a more academic setting, who are interested in the genealogy of an idea? They’re really interested in Train.

Speaking of the genealogy of an idea, that segues nicely into my last topic, which is about the history of making games itself. This is a quote from a 2008 dissertation called “Postcolonial Imaginations” by Doctor Francisco Ortega-Grimaldo, an associate professor in graphic design at Texas Tech University:

The research and study of board games could be seen as a ‘dead science’ for many, especially now that a well-developed, digitally interactive media has found ‘videogames’ to be a very prolific market…. Researchers have sporadically appeared and disappeared, leaving a legacy that few have systemically (sic) followed.

He goes on to catalog game-oriented anthropological and historical associations which arose and expired at various intervals from the 1970s onward. He seems to suggest that curation of games and their own history struggles to cohere. Do you think this is accurate? Why or why not?

I occasionally get the chance to talk at universities for people who have conned their way into teaching a class on board games (laughs), and I’m deploying that specifically because it’s hard sometimes to teach a class on a subject you might care about, but which lacks a lot of academic approval.

One thing that always happens—always happens—is that, if it’s the first time a class has been taught at their institution, the teacher always says, “I cannot believe how much there is to teach.” And I always look them in the eye and say, “Of course there is.” Games are about as old as textiles. We have departments that study the history of textiles, and games are every bit as antique. We’re dealing with some of the oldest cultural productions in human history here. This is as old as a fiber in a cave!

That being said, games do get studied, but they get studied in slightly peripheral ways. They get studied in the context of the history of psychology, as a function of print culture…. So, for example, in English departments, I would occasionally find Victorianists writing pieces on Victorian board games. There’s been more recent academic interest in trying to sort through toys and objects.

Some of the difficulty to cohere has to do with the bias against childhood. The matters of childhood are not as studied as the matters of grown-ups. So doing a dissertation on kids’ games is going to seem a little frivolous.

Play is not productive.

It’s not! In fact, that’s what makes it so interesting.

And there has been a lot of really good movement here. The movement I haven’t really seen yet, however, is some kind of robust theorizing that talks about how we can sort and understand those objects.

So, taxonomy

It’s more than taxonomy. I think what happens is that people fall into the trap of taxonomy, and what they’re lacking is a critical language to even talk about the objects. And so even really interesting and useful books such as Flanagan and Jacobson’s Playing Oppression, which just came out…. It’s a fine book and does a lot of really good work, but it lacks a serious way of talking about games mechanically. It describes mechanisms as systems, but it doesn’t theorize about the player.

It ends up accidentally presenting very bad reads, like “If I’m playing a game about colonialism, then I must sympathize with imperialists” for instance.

Yeah. If you slide that assumption out of that context—

You can end up saying, “If I go see Shakespeare’s Richard III, am I a megalomaniac?”

“Games are about as old as textiles. We have departments that study the history of textiles, and games are every bit as antique.”

And this runs counter to the gameplay of one of your own designs. John Company is a game about running the British East India Company and I recently played it three—no, four—times. I hate to say this, but my group was laughing out of shock. “My God, I can’t believe we’re doing this.” That doesn’t mean we were participating in it. We observed the forces that pushed us to provide dividends, to pay out retirements, to pay out people, to commit to the morally abominable.

That didn’t make us complicit. It made us more aware of those points when we say, “It could never happen here or happen again.” As we’re seeing across the globe, a lot of “this” can happen and we can definitely end up being the ones doing it. Dissociating from historical events is unhealthy.

Right. One of the trends I’m so alarmed at in board gaming is that publishers don’t want to do anything controversial. They have tended to find themes that will not bother anyone.

It makes sense. It’s market behavior. People are finding that nature themes do really well. Part of this is because of Wingspan, but part of this is because it won’t ruffle feathers. [Pun intended? Ed.] I hate this because it’s abdicating the expressive range of games, and so I do everything I can to push against it.

One of my favorite recent books on games is C. Thi Nguyen’s Games: Agency is Art. It does the work of thinking about “What is a game?” and “What is a player?” Let’s actually start thinking about what we’re doing when playing these games and about the evolution of an aesthetic language.

I’ll show my hand here: As someone who comes from literary studies, I think Shelley’s poetry is important, but so is his essay “The Defense of Poetry.” That’s why I write designer diaries and I’m interested in folks who are doing the actual critical work of figuring out how to talk about these things.

It’s not so dissimilar from what happens in film. I mean, you get all those young writers at Cahiers du Cinema: many of them went on to start making movies, and these were critics who were making movies. Before I was designing board games, I was writing board game reviews and just trying to separate the games which resonated with me from the games which weren’t. I was asking how I can use that to inform my own critical language as a player and designer of games. These trends just take a really long time.

I’m glad that there are so many people studying video games now because video games are extremely important. They’re every bit as important as film or more important. I just think play matters a lot and is worthy of study, but this is the kind of stuff that takes a really long time to develop.

And I’d argue that, speaking of taxonomy, we’re reaching the end of our current [set], the taxonomies we put on BoardGameGeek: trick-taking, auctions, bidding, etc. It seems to be breaking down as it falls further and further away from how games are actually experienced.

And I just think taxonomy will. It’s the greediest of academic pursuits. It will eat every moment you give to it. I often think about Linnaeus and Darwin, right? All of this effort spent to figure out what made one bird a different species from another. All of this effort in the late 18th century to categorize the world down to the last detail. Darwin argued in Origin of the Species that this is not observing the system at work. The taxonomy is actually hiding the essential machinery of the world!

So I am naturally skeptical of any kind of taxonomical impulse. Everyone gets tagged in a Twitter argument where someone’s like, “Is Arcs a trick-taker?” Or they’ll say, “Is this a wargame? Is that a wargame?” And I just want to be like, “I don’t care.” In fact, I’ll go so far as to say that I’m upset that instead of talking about the game, you’re talking about which bin you want to store the game in…. I don’t want people mounting these games to little pin boards like they’re butterflies in an effort to put them in different boxes.

The thing dies. That forgoes—I mean, speaking as someone who does criticism, that forgoes a lot of its value. I’ve talked about this before: if you think of performance as a dance, criticism is dancing back. It’s the audience giving some sort of representative response of the audience to the work, regardless of whether or not it’s accurate.

It’s trapped in amber, trapped in time, trapped in all the assumptions you make because you’re living on planet Earth and you had an education. But [taxonomy] bypasses all of those parts to commit the work of a vulture, to take from a dead body.

Back to the “lack of coherence” part of Ortega-Grimaldo’s dissertation, I found my way to one of the most neglected booths of Pax Unplugged back in December, 2023, and that was a historical recreation society. I played some of the games they laid down, like Nine Men’s Morris, which dates back to the Roman Empire. I was rudely surprised to find a catch-up mechanism in the form of “flying mills.” Basically, when you cut down a certain number of your opponent’s pieces, they’re allowed to have them fly across the board instead of moving adjacently. Catch-up mechanisms are thousands of years old!

For some reason, I found it slightly infuriating that we believe that catch-up mechanisms are a hallmark of “better,” modern design balance. It seems like we, as gamers, have something of a bad grasp on the history of the thing we’re playing. We don’t approach novels or or movies agnostic to the history of moviemaking, bookmaking, or writing. But when it comes to games, we basically say, “The moment I entered the hobby is the moment where the hobby begins. Everything before that doesn’t matter.”

I think that you’re pointing at a kind of presentism, right? I mean, there’s a common occurrence where somebody recommends a book and somebody jokes, “Is it just that this was the only book they read in the last couple of years and they forgot how wonderful it was to read a book?”

I think that dynamic can happen a little bit in games: there is a little bit of obsession with the current mode, the current mood. People will tell me constantly, “Games have never been better than they are right now.” In some ways, I agree, but I also think that it’s easy to neglect the deep dramatic narrative, the ludic traditions that all games engage in.

When I look at Rob Daviau’s work on the Pandemic legacy games, which I think are very good, I see the application of a dramatic, long-form television structure being brought to board games. I think about prestige television in the mid-2000s and applying that seasonal framework, those long arcs, to the board game form. And so I can admire the hell out of Pandemic Legacy, but I’m not going to say that Daviau invented the cliffhanger.

I wrote about TV for a long time, and you’re dead right. I wrote during the peak of prestige television, right before the money ran out. I was writing about TV and watching tons of TV. Over the COVID pandemic, I finally finished Pandemic: Season One with my wife and I noticed a lot of the same structural beats of a modern TV season.

It’s called Season One, and that’s giving the game away a little bit. And there’s nothing wrong with it. So much good innovation happens because of these cross-media good times. There’s a better word for that—

Cross-pollination.

Yes, that. Cross-pollination. That’s what I’m looking for. Yeah, I think Pandemic: Season One is a great example of transmedia pollination. However, if you don’t acknowledge that, it can seem like a lot of people are being much cleverer than they actually are, and it also starts to mistake the process of innovation.

Me, I never feel like I’m innovating when I’m working. I feel like I’m trying to learn the lessons of my previous work and apply the lessons that I’m seeing from other pieces to current projects. I’m really just trying to say, “Look, I saw an RPG do this. I think that some of what they realized could be applied to a tabletop board game that came about when I played this wargame, and I think that this framework might be more appropriate in a more mainstream strategy game.”

“And I just think taxonomy will [take up all your energy]. It’s the greediest of academic pursuits.”

The work that I’m doing as a creator there is really just networking, plugging plugs together. But I sort of think that’s all creation ever is. To me, the spark of creation is a spark generated by taking two plugs and plugging them into each other, not, you know, having some good idea hit you like a brick from a cloud.

Or like an apple on one’s head. I think there’s a certain amount of arrogance in the assumption that the apple gave Newton the idea of gravity. There were probably a series of assumptions that he made up to that point, which then were given the eureka moment.

To go more into that and touch on something that’s very relevant now: this concept is part of what people use to justify AI. Essentially, they ask, “How is AI doing anything different from what artists do?” To a certain extent, I’m exhausted by the entire discussion and expressed that in my satire, but since we’re talking about something pretty adjacent to it, I feel like we have to put that out there.

Right. I feel like building an anti-AI stance on ethics is—I wouldn’t do it. I think it’s strategically a bad move because an ethical AI framework will come by [at some point in the future]. To me, it has to do with the machinery of how different types of machine learning actually work, which is interpolation.

Right.

AI, to me, is like intellectual motion blurring. It’s looking at two frames and trying to guess at the one between them. And the result is increasingly muddy, increasingly imprecise, because it’s not being guided by a high argument. It’s only being guided by an effort to produce something that looks like it was produced by a human. So, to me, at the end of the AI road there’s a lot of lifeless art that looks really good.

And I won’t even say that’s unethical because I don’t think I need to. If it were producing things that were actually good, maybe I would want to build my argument on an ethical framework, but I think it’s fundamentally producing garbage, so I don’t. It can make a gorgeous knockoff like a Delacroix painting. Good for that. But there’s no consciousness animating that object, so the object’s not interesting.

“If [AI] were producing things that were actually good, maybe I would want to build my argument on an ethical framework, but I think it’s fundamentally producing garbage, so I don’t.”

“Lifeless.” I want to dwell on that a little bit. I think our life does inform our work. To give a pop-culture example, Anne Rice wrote Interview with the Vampire after the death of her own daughter due to leukemia, right? [Themes about blood] mixed with her depression to create a very elegiac book. And that’s something AI just can’t do. It has no life to live. You can’t ask it, “Pretend that you had a daughter who died of leukemia and then write a book.” That’s an entire series of therapy and grief sessions that AI can’t go through to inform their work. In a sense, we’re infected by our lives.

What can the average gamer gain from a historian’s approach to gaming, as opposed to gaming’s approach to history? I know games like to examine history outside of games, but how can the average gamer approach this medium’s history in a way that enriches them? How can they cultivate it?

The concept of play is…something people forget about. I think oftentimes they think about having fun and don’t think about making play. I love games, but what I really love is play. I started realizing this when I would tell stories about growing up—I grew up in a family that played a lot of games, but I would never describe my parents as gamers. It would never even occur to me because that was an identity that didn’t exist. What they were interested in, though, was play. And when you open that up, it means that you stop having such a limited imagination about what games can be.

And, you know, I’ll pick a really dumb example. I know a lot of people who love board games and hate sports, and sports are play! It’s a different kind of play, but y’all are part of the same family! And if someone can care about the Super Bowl and another cares a lot about an Essen release, then those two people are cut from the same cloth. When you start to broaden your own thinking about play, you’ll start to see that. The games you play, the tradition they participate in, is a tradition that is much deeper and more far-reaching than you might have realized, and that will give its own import.

In terms of thinking historically when it comes to history games, I think it’s important to remember that games are little iceberg tips. They’re manifestations of vast structures, vast structures of feeling, right? So when you sit down to play a game about Gettysberg, you’re not only playing a game about Gettysburg, you’re playing every game that’s ever been made on Gettysburg, every book on it that people have read or thought about, the actual lived experiences of the battle being filtered through many generations of stories about those stories.

“What [my parents] were interested in, though, was play. And when you open that up, it means that you stop having such a limited imagination about what games can be.”

When you’re sitting down and playing through Gettysburg, all of those things are existing at the same time. For the same reason, I find that when I sit down to play a wargame, the first thing I want to do is learn more: not just about the actual game, but about the whole genre that it’s operating in. For example, tell me about the history of the combat results table; that’s fascinating. I want to learn more about that because that’s a history about how people deal with uncertainty.

That kind of interconnectedness is true of every game, from a Knizia auction game to the Campaign for North Africa.

I want to discuss an anecdote related to what you talked about with regard to Civilization, the nature of play, and taxonomy.

I had an experience at Pax Unplugged which was kind of informative. When I moved between the latest games in the exhibition hall, I realized that there was this low “number chanting” that people were doing between tables. I thought about fashions of play.

I agree with you that taxonomy is consumptive. It burns you out and doesn’t give a whole back in return. But I do think there’s such a thing as fashions of play, things that come in and out of style, things that people prefer for whatever reason—you sort of cover this in your GDQ presentation with regard to design priorities.

And so when I moved through the various popular titles making the rounds, like Pirates of Maracaibo and Rats of Wisteria, I concluded that the current fashion still consists of various versions of resource optimization—the stuff you’d expect from Vlaada Chvatil ten years ago. He hasn’t designed anything recently, from what I can tell?

That’s true.

And I thought about Civilization and the fact it has very little abstraction. Everything is concretized into numbers, a spreadsheet of numbers.

Right.

What is the appeal of this style of play, where we’re basically crunching numbers and doing basic arithmetic? What are the limitations of that style?

I think about this in the context of puzzle design. I play a lot of OpenTTD, or I used to play a lot of OpenTTD, which is a transport tycoon game from the late ‘90s. I was teaching my son how to play it and we spent, oh, the better part of an afternoon designing optimum rail layouts for train stations. Now, the puzzle being solved here:

You have a certain number of trains that are coming into every station on some time interval, and from that station, they need to be able to leave to access a wider network, and then they need to access that wider network without slowing down traffic on the wider network. And this generates a ton of interesting spatial puzzles, but does not generate narrative. It has no interest in narrative.

So, with some exceptions, I think that puzzles are generally really bad about generating narrative, but what they are really good at generating is engagement. And I don’t think this is unique to games at all. I mean, I love doing the New York Times crossword puzzle whenever I get a chance—and I can remember specific clues that I thought were clever, but I rarely remember the experience of solving a particular crossword puzzle. The optimization puzzle you encounter in a lot of board game design is very similar. It’s engaging! For sure, it’s engaging, but I don’t think it’s narratively engaging.

Here, I’m splitting hairs a bit because of course I can build a narrative out of my successes and failures while solving a puzzle, right? Certainly, if you’ve ever played Minecraft and spent a long time trying to dig your way out of a hole, that’s a spatial puzzle, but also there’s a narrative component to it.

But I think that the main thing that a lot of euro designs are—and I feel silly even using those terms…. I think a lot of game designs are interested in player engagement and not storytelling. Those things can look the same if you’re just walking by a table; you see players caring a lot about little scraps of paper on a table.

But I think the output is totally different. Any kind of engaging play is fundamentally rewarding you, the player, and giving you reinforcement. But when you’re working on a narrative level, I think it’s creating something for the entire group. That’s the fundamental difference.

I think a lot of the inputs begin to look the same. There’s a ceiling at which a lot of puzzles, no matter how you’d like to dress them up, involve a lot of the same components, either spatial or quantifiable. They can be given various configurations, but they often look the same, really. And I think that formal structure lends itself to what we discussed: a kind of obsession with taxonomy in board gaming.

I was having a conversation with someone once about definitions of the novel, and I was sort of fumbling with it because it wasn’t an area where I’ve thought a lot about. They reminded me that novels are fundamentally about, well, novelty. They’re about an innovation of form. And as soon as they said that, I was like, “Of course.” With novels, the only thing they have in common with each other is that they’re trying to take the form to a new place.

I feel a little bit the same way about a game. It’s a lovely thing to play the most recent Rosenberg or Knizia titles, where you can see their thinking slowly evolve. But it’s a little bit like encountering a piece of music by Bach or something. It’s expertly done, and maybe you’ve never heard it done quite this way, but here is someone working in their established mode.

But to me, if I’m thinking about games as a form, the elements of play that excite me the most are when I sit down to play a game and it does something I’ve never seen a game do before. And to me, that’s more likely to happen at the level of narrative than at the level of gameplay.

Not only that, but if you work on the level of gameplay, you can atomize the individual players of a game as opposed to creating a collaborative environment where everybody’s participating in the story.

Right.

Earlier, you briefly used the metaphor of a theater: “I try to remember constantly that I’m working on a little stage that’s in people’s basements and kitchens and cafes.” Would you say that players are closer to being the actors, authors, or the audience?

Actors, authors, or the audience…. I mean, the thing about play (I’m about to cheat on my answer a bit) is that players are operating on all three registers. They’re authoring the experience because they’re designing their own strategy or presentation. They’re performing the experience, and then they are reacting to the performances of others.

This is actually why people get so worried when they have to play morally compromised positions: not only are they having to experience it as an audience member, they also have to express it as an actor taking on that role. And they might—in the sense that they had to design a strategy to win—they might also be authoring that experience at the same time.

And that’s a tremendously challenging thing to do. I sometimes use the example of Iago when the question of playing evil in games comes up. I always say, “Imagine going to see Othello and Iago comes out on the stage and says, ‘I just don’t want to do it tonight. I can’t kill Desdemona, not again.”

And I think—well, I think this is laughable—I think if the actor were being asked to author those lines every single night, there’s something almost horrific about that, right? You’re constantly having to engineer the evil deed, not just perform it. To me, that’s what gives games their narrative punch and power because they don’t just ask their players to play the role. They ask players to design a role, to collaborate with the author or the team that authored the game.

Shifting between the registers of actor, audience, and author…that reminds me of something. I wrote a review about the board game adaptation of Frostpunk recently. I wrote about how the adaptation was rather literal: it followed the original video game’s design closely. But shifting the context from a solitary experience to a committee single-handedly shuffled the dynamic of the same problems so much that it became a different game.

Right.

So that’s an example of how being perceived by others, of how performing at the table, alters the context to such a degree that you do become actor, audience, and player all at the same time.

Right.

Now, if we make an honest attempt to move games away from taxonomy, are games defined by interactivity, reactivity, and systems? Do you think that language is more accurate?

I mean, I think there’s some overlap or even dissonance with stuff like audience participation theater, British pantomime, and non-ludic forms of play which invite the audience to authorship. How do games differentiate themselves from that?

Fundamentally?

It’s a tough question.

It’s a huge question. When I used to talk to classes about games, I would say that basically there are two definitions of “game” that I liked.

One of them is “a space that adjudicates a winner.” Fundamentally, a game is a decision space that is going to sort players into the players who have won and players that have not won. And as long as a game does that, I don’t really care what happens in the box. If we all roll a die and the highest roll wins, that’s good enough for me. That’s still a game. That’s a definition that is very mathematical in its formulation, in the sense that you can imagine defining the Prisoner’s Dilemma with that. The reason I harp on that is because it helps us understand the stakes of what games can do, which is always why I feel very sensitive about experimental victory conditions.

Because when looking at experimental victory conditions, people will say, “Well, what if the player has to decide what winning means?” I think of that as designing a car, but you’re not putting an engine inside it. I can still say it’s a car, but you’re not doing the elemental task of the game. And I think that cooperative games also still do this. It’s just that cooperative games are fundamentally single-player positioned in the game theory sense: you have the players working collectively against the puzzle of the game.

So that’s one definition for “game.” The other definition I like is “a game is any form of structured play.” That definition has a lot more purchase in the context of anthropology and homo ludens [Latin for “the playing man” and the name of a foundational text in game theory by Johan Huizinga. Ed]. The moment we begin to structure play, we are now engaged in a game and not just play.

From here, there’s a whole range of…. If you’ve played tag on a playground, that’s a kind of structured play, but you might not have known who was going to win tag because tag, even as structured play, doesn’t contain an endgame function. The characters, the players, just get tired.

Exactly. It ends when they feel like it.

Yeah, it ends where they feel they’re at.

Now, the thing is that I think these two definitions, which are about as different as possible as two definitions could be, are completely valid definitions. I’m not hunting for the one pure definition of “game,” but what I like about both of them is that they both emphasize structure and structuration. It’s an arrangement of values. So, to me, games are about the arrangement or rearrangement of player relationships.

I can play a game with my wife, we can sit down at that table with the relationship between ourselves, and the game is going to reorganize our relationship. If we go outside to play tag with our kids, we’re no longer husband and wife: we are tagger and taggee.

Obviously, this is the idea of the magic circle and what it helps us understand. But the magic circle also has this problem: we don’t exactly stop being husband and wife when we’re playing tag. The real world sort of permeates it.

The hope of the magic circle is that the game doesn’t bleed out, but you certainly can’t stop the real world from bleeding in.

Exactly. I wrote a preview about a game called Collectionomics where people bring their real-world collection(s) in order to play a party game, and that’s intentionally breaking the magic circle to draw your outside interest in.

I think that sometimes the magic circle can become a temptation or a crutch to say, “Oh, the other parts outside of it don’t exist.” This connects to Rob Daviau and your comment that he’s being a literalist with the concept of “a game with a memory”: he’s excluding the players themselves from the equation of memory.

Yes.

From that perspective, you just think about it purely in terms of the changing components within the box.

Contemplating that change in registers (actor, author, audience) and that leaky magic circle…. How do you structure tone when designing a game?

In the case of John Company, I and others found it very satirical. It had a clear authorial tone of satire to it. We noticed that it showed how stupidly and easily all these systems were prone to corruption and graft to the point that the health of the Company was almost secondary. “Oh huzzah, the Company survived. Who cares? What do I get out of it?”

So we’re naturally siphoning cash and reinforcing this. If everyone has agency, how do you bake in satire?

Well, here I’m thankful to operate within a tradition that has the satire baked right in. The British often say about themselves that they’ve always had a great sense of humor about the horrible things they’ve done (though I’m not sure I fully agree with that). But even within the era of John Company, people were good at making fun of themselves.

When we tell stories about the past, we often present a version of the past as we like to tell it, not like it was. So much of John Company’s calculation is about trying to get a sense of what it felt like in the moment, not about moralizing it. And at the time it was cruel and arbitrary and unusual and funny and capricious and all those things. It’s like a war story during the war.

If I’m reading Niall Ferguson’s Empire, he’s going to have a very stodgy, stuffy, upper-lip image of the British Imperial exploit. But that’s an image that has more (or as much) to do with decolonization in the 20th century, with imperial apologetics, than anything in the 19th century.

Whereas in the 19th century…. I think about Mrs. Jellyby in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, where the empire and its “charitable efforts” were constantly eviscerated. In the moment itself, people understood that what their empire was doing was risible, and so let’s embrace that moment as opposed to a more, well, processional sense of one’s dignity and self.

I mean, I’m really just going against the Whig school of historiography here.

The Swiftean nature of John Company shines through.

And you’re right about empire. I’m personally quite familiar with Tacitus because I translated a lot of his work in college, and he was so scathing about empire even while he, a magistrate, was constructing it. There’s an element that, even at the time, is very self-aware, and we always like to think all that criticism as an afterthought.

But when postcolonialism and decolonization come along, criticism shifts toward defensiveness.

They do that as soon as the past gets freighted. I mean, this is why—sorry, this is a sprawling answer—this is why I try not to be too much of a modern moralist when it comes to viewing the past, because that necessitates a deep flattening of the past. And that aesthetically robs a game of some of its most powerful tools.

Refusing to flatten the past that way means that you ight, on the one hand, be misunderstood. Someone could play the game and say, “Oh, what a lark empire was.” I would say, well, that’s certainly a reading. I’m not gonna tell you that your reading is necessarily wrong. It’s just not my reading of it.

One reason why we decided to make John Company in the first place was we felt that there were a lot of games about empire, but it’s too easy to build a stilted modern critique or be hagiographic about it. So I wanted to just try to capture the lived experience from the perspective of the people constructing these edifices. John Company is kind of the result.

And the result is something that feels more like a novel than a game. One of the kindest things people told me about John Company when they started playing it was that they felt like they were playing a Dickens or Thackeray novel. Perfect! The people who were living at that time would sometimes feel that they themselves were living in a book.

I think you’re touching on the need to capture the day-to-day living in what people idealize as perfected history. We talk about “the Enlightenment” and “the Renaissance” and all these things, but nobody knew they were living in the Renaissance at all. So John Company often feels like the day-to-day endless bureaucracy, the memo meetings, the board meetings to construct the endless bureaucracy.

It doesn’t feel banal, but it does feel picayune. It definitely feels like sending ships over to carry tons of opium was just a rational decision made in the rather boring interest of economic solvency. Acting like a board member, you harrumph. “Well, I’m not going to judge whether or not anybody does or doesn’t buy it, but I have my fiduciary duty and I have to face my family the day after tomorrow. I have to think about my friends, the people I actually know.”

One of my favorite decision spaces in John Company is towards the end of the game. Players will say, “Hoo boy, I have a lot of end-round upkeep. I would love to do something—” It’s not even a favor for the greater good or anything so charitable. It’s a favor for a friend, and they say (sighs), “I just…can’t.”

And oftentimes they’re not actually worried about paying upkeep. They’re going to make upkeep, but they just want, like, a little bit of a rainy day fund. And yes, it’s completely banal.

It’s weird because I played Thunder Road the other night. I really like Thunder Road because it does the opposite. It makes you behave in anti-banal ways. When I play Thunder Road, I take every risk I can possibly take.

Which you would never do if you were actually there.

Exactly. It’s just a good example of deeply situating you in a place. Thunder Road and John Company are as different as two games can be, really, but they share this interest in grounding a player in a certain subjectivity.

Yeah.

For me, one example of that grounding in John Company came from paying out retirements to old officers for victory points and prestige. I suddenly got insight into the vast retirement of packages of people who are on company boards. I realized, “Oh, this is just a different type of investment: you get to keep the rolodex of a well-connected employee.” Sure, you can say that so-and-so’s been with the company for many years, but it’s actually a highly rational investment. The reason you have far more compunction to pay them (as opposed to a rank-and-file worker) is because they’re still doing a job for you.

And the rationalizations sound familiar and timeless. “Sure, the money’s dirty, but I have all these retirement packages to pay for, and didn’t they earn their retirement?”

I’m not trying to penalize the early folks who said this, but…. Well, this is especially funny. There was this amazing moment….

I mean, one of the things John Company does is allow for our history. Of course that’s an important function of any historical game. The past of our own moment will still end up informing the game. Somebody who played a game of John Company once said it was so odd because “India was very stable and we just traded freely. It felt weird because everything was peaceful and fine, and we made money. And I should feel bad.”

I said, “Why should you feel bad?”

They said, “Well, because of everything that happened in India.”

“Well, none of that happened in your game.”

One of the things that will happen in John Company is that you’ll play a different version of the East India Company. And, you know, of course people are going to have feelings about tariffs, the consequences of protectionism in the English wool market. Maybe that’s going to rise to the level of some kind of political anguish.

People have a hard time disentangling the experience of the game from the reality of the past they inherited. That’s okay, too! Every player who plays any historical game benefits from the fact that they live in a world that has a living history and something they can compare the game to.

That can give the game a burden because if the historical game can present something so extreme that it doesn’t make any sense, but it also gives the game its power. It lets people start comparing and realizing that if this would have happened a little differently, maybe this whole other chain of events could have happened, also.

It accounts for the leakage in the magic circle.

I think that part of the issue is that designers assume the magic circle is hermetically sealed, and so they sort of write off any of the stuff that leaks out. They don’t realize there’s always going to be a certain part of this where you can’t control people’s reaction. Instead, they project a tight feeling of control over everything that happens in the magic circle.

When I first started playing and designing games, I was one of those people who believed in a hermetically-sealed magic circle, and this was just a place of privilege. I had grown up playing a lot of board games, playing games where players would be extremely mean to each other, and you would ask for, you know, a bit of sportsmanship. It’s fine. Maybe you get a little upset, but it’s just a game.

“Every player who plays any historical game benefits from the fact that they live in a world that has a living history and something they can compare the game to.”

And what I found as I started playing games more is that the magic circle is, in fact, quite leaky, and it’s not that hard to put in a little bit of protection to safeguard it. I played games with people who were going through things or subjects that mattered to them on a level much deeper than I’d guessed. It occurred to me that we could put in some protection for that. This is the biggest reason why, for instance, John Company has a little note that says, “Hi, this is a game that deals with subjects around imperialism that aren’t suitable for every group.”

If you just want to hang out and play games of Skull with your Friday night group and you don’t want to think about history, I get it. Guess what? I don’t always want to watch War & Peace I mention that because my wife and I were watching the Soviet War & Peace adaptation, it was a wintry day and I thought it would be perfect. But there was a lot going on in the world and after about an hour, she looked at me and said, “I just don’t want to do this.”

I said that’s totally reasonable. We don’t have to do this at all. But I’m the kind of person who does. If I want to listen to a sad album,find me the saddest album in the world. I want to plunge into the depths of despair because I love when a piece of art makes me feel something. But that’s also the privilege of someone who’s been lucky enough to have a pretty stable life.

I always want to check that privilege. It’s why I’m more inclined to put a small disclaimer at the front of the games just to make it clear what the game is, especially because I know that the historical games that I work on now don’t exist in the context of my academic work; they exist in the context of my hobby work. If someone has only played Root or Oath or Arcs or something and they think to themselves, This is a Cole design called John Company. Maybe it’ll be about companies.

Well, my guy, you’re about to actually move from one genre to another. I really want to make sure they know about the size of the leap they’re about to take.

From John Company, let’s shift a bit ourselves and leap back to play.

In terms of discussing play without taxonomy, what is an example of play that is, for lack of a better phrase, falling out of fashion? Do you have an example of something that would have been considered the pinnacle of play fashion and is now considered less so?

Whenever I have to describe what I do to relatives, I have to tell them that I fundamentally work in the entertainment industry. I make things people entertain themselves with, and that means I work on the subject of fashion.

If you’ve ever taken an economics course, you know that there’s this supply demand shifter, it’s called fashion, and nobody knows how it works. You think that would invalidate an entire discipline. If I said, “Here’s a magic button, it changes temperature, and we don’t know how it works,” then I guess meteorology is over. But it doesn’t seem to bother the economists at all.

I know fundamentally that the games I work on…they resonate with people now. They may not resonate with people in the future, they may not resonate with me in the future. And that’s just part of what it means to work in entertainment.

Fifteen or twenty years ago, the gaming audience was smaller and had more limited tastes. If I had to give one fundamental dynamic, it would be the smaller total audience of gamers, and they had narrower tastes. Now, that was good and bad. It meant that if my tastes aligned with that core group and I looked at the BGG top 100, then, my gosh, it’s a perfect list.

When you look at it now, you see different groups of players that have different preferences. There are some people who think Gloomhaven is the greatest game ever designed. There are other people who think it’s Brass: Birmingham. The critical difference is that if someone thinks Brass: Birmingham is the greatest game ever made, then they probably don’t think Gloomhaven is even close. So what we’re looking at is a number of different interest groups.

“If I had to give one fundamental dynamic [for games fifteen to twenty years ago], it would be the smaller total audience of gamers, and they had narrower tastes.”

As for myself, I have a pretty wide diet as a gamer. I play all kinds of things. Blood on the Clock Tower was probably my favorite release from two years ago. I played dozens of games of Blood on the Clock Tower. This year, most of the games I’ve loved have been hex and counter wargames. One never knows what direction I’m going to spin in.

I do think that players are…. I think there’s a real rich market for people looking for very interactive designs that are very story-first. I think that’s one thing that happened—a lot of board games were story-first. These games used to be called things like “Ameritrash.” Really, they’re just narratively-driven games.

I think an interesting thing happened in the 2000s: a big body of those players moved into role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, and then another group of those people went to what we think of as “eurogames.” [Case in point: Roll Player, the dice-manipulation eurogame about making a D&D character sheet. I got to talk to them recently and they were delightful. Ed.] In order to capture that story, you had this movement of narrative games that were inflected by euro mechanisms. But the problem with that movement is that people were fundamentally making eurogames that were dressing up like narrative games. So there were very superficial gestures towards story, but these were fundamentally engine builders.

I think that CGE is a really interesting company in this regard because of titles like Sanctum or Adrenaline; great examples of a very good eurogame that is dressed up like an ameritrash game. I’ll even put Dungeon Lords in the same category. It’s interesting to think about someone playing Dungeon Keeper growing up and then designing Dungeon Lords because the latter is such a carefully calibrated puzzle.

Yeah, and Dungeon Keeper was not.

No, Dungeon Keeper was extremely chaotic, or at least it seemed that way when I was playing it as a kid.

I think of myself as participating in a wave of designers kind of starting in 2015/2016 who looked at a lot of those euro-driven, mechanically focused story games and said, “Could we actually go back a step further?” And what does it mean to do story first, to do board games that are less interested in questions of balance and fairness and more interested in questions of narrative expressiveness?

For my own design practice, that has been a rich vein, and it’s a place where I don’t feel like I’m at the end of tapping. In fact, in my capacity as the creative director here at Leder Games, when we look at our five year—our ten year—plan, I look at that and say there’s a lot more that can be mined and explored here. There are many genres that haven’t been well-served narratively by board games and that’s the direction we’re going to take.

In passing, I’d like to pull out Tzolk’in as an example of how going back to older styles, to older assumptions, can prove to be an enriching experience. It’s like going back to an ‘80s or ‘70s movie made entirely with an ‘80s or ‘70s sense of aesthetic and style: it almost becomes timeless because of that commitment.

Right.

As opposed to ones that tried to transition to new movements and got caught halfway in-between. Perhaps they met with critical acclaim because they were pushing the envelope at the time, but they become less entertaining when you watch them in a modern context.

What’s really interesting about Tzolk’in to me is that it’s consumed by timing and puzzles and built all of that into an abacus on the board. The gears themselves are a learning aid to the puzzle, making sure that everybody’s playing their tightest, most optimized game possible.

And if you embrace the fashion assumptions of a euro, I’d say it’s pretty high up there. A lot of people say, “Well, I think it’s gonna be dated.” I think the opposite will happen. I think it’s going to be considered some peak or point at which the design fashions of the time realized their goals, met them, and then tried to pivot toward stuff like Teotihuacan or Dwellings of Eldervale.

I was actually somewhat appalled by the combat system in Eldervale: roll the dice and pick the highest number.

It’s funny you mentioned Tzolk’in because I have a category…. I like eurogames quite a bit. But for my money, I think about the early aughts euros (I’ll put Princes of Florence, Caylus, andAge of Steam in this category) where I still play those games regularly and think about them. Heck, I’m playing El Grande right now! I’ve been playing with a group digitally and we’re in our second or third game. Maybe just the second. It’s still a fresh and clear articulation.

I look at El Grande and say, “I don’t think any other area majority game is half as good as El Grande.” I’ll go so far as to say that I don’t think any worker placement game is half as good as Caylus. And Tzolk’in is interesting because I love it. I think it’s a really compelling design. I look at it and see a mechanical clarity to it that I admire. And I’ll use Lopiano’s games, like Calimala…. It came out a few years ago and I adore it because it reminds me of those classic euros.

I’ve played more recent games by that same designer. I think they’re fine and well-built, but they are so mechanically baroque that as a player, I disengage a little bit. I thought to myself that what is fashionable in eurogames is something that I don’t personally resonate with. Maybe my own tastes have shifted a little bit to the point where if I’m going to play a euro, I want it to be as mechanically direct as it can possibly be. I’m not really interested in extremely baroque conversion puzzles.

But isn’t there such a thing as timelessness? Maybe even things that will be timeless because they are of a time? I’m speaking as someone who loves the Baroque era of music, who loves Bach, who loves Vivaldi—those things are my go-to music.

Yet I realize that the period had to end, that it had reached a point in the aesthetic where there was nothing left to explore.

And then we transition.

When people talk about their love of classical music…. I mean, music is…. My goodness, I’m always searching for transmedia metaphors.

There’s a kind of mean trick that history and aesthetics plays on children, including myself. As a kid, I remember listening to the Goldberg Variations and thinking, I love this. Is there more of this? And you learn that, oh yes, there’s a lot more.

Then I would tell people I love classical music. It didn’t occur to me until much later that there was, in fact, no new classical music because there was the Romantic period, then the period after that, and then we’re soon into atonal music. There’s this whole story. The fact that I was attracted to old-fashioned music? Well, that had to do with politics and aesthetics and history and all sorts of things that created a little zone for me, but for Beethoven, the question of what a symphony could accomplish was alive and unanswered. For a listener in our modern time…well, that question’s been answered.

So here’s the thing I love about working in board games: this is a living field to me. Everyone, as far as I’m concerned, has agreed that games are a kind of art. I don’t think it’s even worth spending time thinking about that question anymore. We don’t know what they can do. We don’t know how they talk and what kind of things they can say. These are unsettled questions, and it’s delightful to be working on games and trying to answer those questions. What can a game do? I love to sit down to play a game and be shocked by what it does…and you can locate that shock in a hundred different places.

Heck, I was playing Mark Herman’s Rebel Fury which, from a passerby’s perspective, may look like an old-fashioned hex and counter wargame, but in the context of hex and counter wargames, it reinvents the genre without using any of the established systems. It’s a totally novel approach. It doesn’t use cards, doesn’t use any little tricks. It’s a straightforward, beautiful design that’s almost abstract, but has such clarity of thought. I played it and thought, My gosh, there’s so much room to explore in the world of the hex and counter wargame, one of the most established genres.

[Cube rail games like] Irish Gauge. A tiny 40 minute 18XX game. How is this possible?

I had the old edition of that…. It was so charming how it captured uncertainty in a genre that usually just does not tolerate uncertainty at all. I think the thing that is so vital about tabletop games—I think this is true for video games, too, but I think it’s especially true of tabletop games—is that there’s a real question about what they can do. It’s worth spending a few years trying to figure out what the answer to that question might be.

I think it’s also worth noting the reactionaries, too. We’re talking classical, so let’s go there. Haydn’s Creation caused a stir by opening with a deafening “Let there be light!” [going straight from pianissimo to fortissimo.] It shocked people! People left! There’s Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. He comes home from the debut crying. No one liked it. It drove people into a riot. There is a group of people with whom etiquette can become so ossified, right?

Yes.

To a certain degree, whenever I look at board game discussions, I find them trailing behind the actual board games themselves. It’s almost ridiculous. It reminds me of that old etiquette and people’s reactions to the music before it had even emerged. The discussions around a lot of them were absurd. In the minutes record of a Leipzig meeting in the 1700s, the town council wrote, “Since the best man could not be obtained, mediocre ones would have to be considered.” They were referring to J.S. Bach!

Yeah, this is a classic problem where I think critics, because they do their work after the game is made, are easily assumed to be at the vanguard because, you know, who can have a fresher opinion than a critic who just viewed the game? But both the people who design a game and critics are encountering the current space and thinking about what’s possible.

Before I made board games, I wrote board game reviews. They weren’t very good. I was just a student. I was still thinking about how we even talk about games. But I really understood, when I started designing them, that my games were extensions of my game writing. That game writing was just forum posts and things where I was just another participant, but I was trying to find ways of talking and thinking about games.

So I do think that good critical work can advance the cause of understanding games, but it can also pull it backwards.

In that case, what do you think the critical space really needs? Can we clone Dan Thurot and Charlie Theel and Mike Dunn? Send them around everywhere?

Of course, that’d be no fun either.

That’s a different problem.

True.

What do you think?

Since you ask…. The critical space right now needs to break down what I’ve always considered “courtly” etiquette. It’s interesting that we’ve used the word “baroque” more times in this discussion than most people use in a year because the first thing I think of is contemporaneous writings on Baroque music, where it’s all so…formal.

Yeah, I mean, to me there are two things about…. Look, I’m not a board game critic, really. I don’t know if I ever really was. But I think there are fundamentally two components to this. The first is the question of platform: where is good writing happening and what kind of resources are benign directed to allow good writing? Things like the shuttering of Dicebreaker, which happened recently, are real tragedies in that respect. [Don’t I know it. I was an infrequent contributor who got the news directly. Ed.] I mean, Matt Jarvis wrote a lovely piece on Pendragon, which I think is one of the most remarkable RPGs ever written. I’m just so sad that if another amazing thing like that happens, there won’t be a Dicebreaker to write a 3,000 word essay about it.

So there’s a question of platform, and thankfully tools like Patreon, YouTube, and Substack—it’s actually easy to get platforms. And I think creators are finding ways to monetize their work where possible or to plug it in. It’s never been easier to create commentary. I think that’s a good thing that needs to happen. That platform question is essential and important.

The second question, though, is about the quality of the work, and that fundamentally is about the quality of the discourse. This is about designing pieces that can be responded to meaningfully. It means moving beyond the “consumer reports” mentality in our writing.