A few years ago I wrote an editorial discussing the shocking majesty of Hidden Frontier, a no-budget Star Trek fan film that reached for the stars and became one of my favorite shows of all time. Since then I ate through every sequel and spinoff and made my way deeper into the lost horizons of Star Trek fan films. What I have found there is a community of creators woven together into a dense tapestry of ideas and filmmaking techniques that puts most modern science fiction to shame. Ranging across the spectrum of budgets, tone, and scope, these creators form a network with its own history and culture, all supplementing one another to create a greater whole. In interviewing these creatives, I found a collective of passionate, unpretentious individuals who make content for all the right reasons, despite considerable challenges. It’s surprising how much these films share in terms of cast and plot elements, often crossing over with one another to make for a narrative framework I still haven’t totally wrapped my head around. Whatever these works lack in sophistication, a problem technology is quickly rendering moot, they make up for in creativity, sincerity, and humanity.

Dawn of a New Era

Even in the early 70s, Star Trek’s addictive vision of hope and decency attracted fan filmmakers. The galaxy of boundless possibility set fire to people’s minds and continues to pull them towards the final frontier. 1974’s Paragon’s Paragon, recently unearthed, is the earliest extant film I could locate. Its quaint presentation belies surprisingly well crafted sets and storylines that feel right at home in the contemplative but campy world of early Star Trek. Such endeavors were difficult to shoot and distribute, and fan films from the early days remain difficult to locate. Things began to change when James Cawley, Elvis impersonator and intern on The Next Generation, began production of Star Trek: Phase Two (later renamed Star Trek: New Voyages). Boasting an Enterprise Replica set and scripts or concepts adopted from the abandoned ST Sequel series, New Voyages was more professional and sophisticated than any fan project yet to see the light of day. The quality of scripts and performances attracted much attention, including appearances by Walter Koenig, George Takei, and others to step back aboard the Enterprise to continue the journey so long ignored by studios. My personal favorite, A World Enough and Time, penned and directed by Far Beyond the Stars author Marc Scott Zicree, is indisputably one of the best episodes of Star Trek of all time.

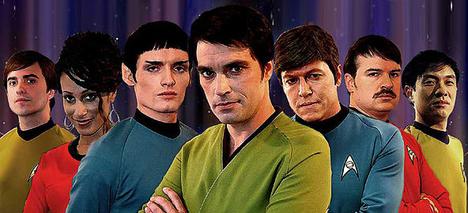

Seeing the success of New Voyages, what followed was a series of projects which fan trek to new heights of quality and professionalism. Tim Russ, Voyager’s Tuvok, brought out Gods and Men and Renegades, seeing the return of regulars from the original series, Voyager, and DS9 alongside Cawley and other fan film actors. Star Trek Continues needs to be seen to be believed; the production full to the brim of original actors reprising their roles, is far and away my favorite single season of Star Trek, bringing the most consistently creative and thoughtful scripts to the fore with a level of quality unmatched even by most sanctioned standards. Prelude to Axanar, a Klingon War era documentary, continued the tradition of broadening Trek’s horizons to new heights, but it was by this time that CBS started to get concerned. What followed was a lawsuit to stop production of Axanar.

The particulars of that suit and its fallout have been well documented elsewhere by people with more knowledge of the specifics than myself. I encourage you to do your own research on that topic if you are curious, but as a lawyer myself I know well the perils of commenting on a litigation that I don’t know the specifics of. The focus of this editorial is on the culture and community of Star Trek fan films, not the specifics of a lawsuit that, by and large, does not have an impact on that community’s work. Suffice it to say, CBS seemed to be concerned with the scope and legitimacy these fan projects were accumulating, not to mention the crowd-funded budgets. Following the Axanar settlement, CBS laid down new guidelines for fan films that threatened to gut the community. These guidelines limited the length, runtime, and appropriate cast of fan films, and made the community fear that their days of journeying the stars were over with.

A Major Upheaval

For a time, the prospects for future fan films were grim. With new guidelines and a new relationship with CBS, creators feared that any new project could be met with legal sanction. Experimental short Pen Pals by Vance Major Owen set out to prove that the format wasn’t dead, and succeeded. The first of what became many projects showed the community that fan films could still thrive after the change of policy. What started with a short on an Iphone exploded into over 150 appearances by Vance’s Captain Minard, a fictional character who started as a one off engineer. Over the course of his career in Starfleet, told in nonlinear fashion, Vance and Minard have crossed over with more fan series than you probably knew existed, building connections and helping projects get off the ground. Before Vance got involved, the community was fractured and disorganized, but his ability to get people together and get projects moving, no matter the size, helped reinvigorate a subgenre its fans feared was soon to die off.

“Vance was the pathfinder of finding out how fan films could be done in the post guidelines era.” Joshua Irwin, creator of the Avalon series said. “He’s also just an easy person to get along with. He’s a good friend. He is a moral person. Just a sincere individual…He’s built an architecture and he used his platform to help other fan film entities come into existence.”

After nine years and hundreds of fan films, Vance is laying Minard to rest and moving on to other projects, including an autobiography currently in early draft form. What might seem a niche and unnoticeable career has taken him far, though. He has won awards, presented at a conference in Las Vegas, and helped spearhead projects across the globe. One of the keys to fan trek’s success in recent years has been the decentralized nature of production. Disparate creators working with greenscreens in home studios can send performances anywhere in the world to be combined by a team of editors and CG artists. I got to speak with many of these creators, delving deeper into what a dedicated community can achieve with nothing more than the right connections and a frightening amount of their free time.

Infinite Diversity Proliferates

Star Trek’s Avalon Universe, created by Joshua Michael Irwin is the most professional and consistent set of films currently in production (at least, of those creators I became aware of during my research). Taking place in a timeline in which the Excalibur was not destroyed during the M-5 disaster, Avalon has eight films out now with four more in production. Joshua always wanted to work on filmmaking and storytelling. His parents were tv news anchors and he effectively grew up in a tv station. “It’s like being in a spaceship watching everyone work together.” He learned the ropes in Fayetteville, Arkansas public access and earned a career in video production after graduating from film school. This career paid the bills and subsequent short films stretched his creative muscles, but it wasn’t until he saw New Voyages in 2006 that he realized how much was possible in the realm of fan material. Vance’s home films showed him that the barrier to entry was only mental. “This guy’s a more courageous filmmaker than I am,” he said of Vance’s low budget shorts, and the two began a phone correspondence to discuss his projects.

Star Trek’s Avalon Universe, created by Joshua Michael Irwin is the most professional and consistent set of films currently in production (at least, of those creators I became aware of during my research). Taking place in a timeline in which the Excalibur was not destroyed during the M-5 disaster, Avalon has eight films out now with four more in production. Joshua always wanted to work on filmmaking and storytelling. His parents were tv news anchors and he effectively grew up in a tv station. “It’s like being in a spaceship watching everyone work together.” He learned the ropes in Fayetteville, Arkansas public access and earned a career in video production after graduating from film school. This career paid the bills and subsequent short films stretched his creative muscles, but it wasn’t until he saw New Voyages in 2006 that he realized how much was possible in the realm of fan material. Vance’s home films showed him that the barrier to entry was only mental. “This guy’s a more courageous filmmaker than I am,” he said of Vance’s low budget shorts, and the two began a phone correspondence to discuss his projects.

Through these discussions, Josh learned that Warp 66 Studios in Arkansas had purchased the old Star Trek Exeter sets, but that they were without electricity. Limitations spur the greatest of creativity, and Joshua realized that a dark ship could simply be explained as a damaged one. Thus began the production of Ghost Ship, the first Avalon story set upon the adrift and zombie-laden Excalibur. Though he expected the films to be ignored at a few thousand views, they quickly shot past half a million, and a larger series was born.

Avalon is only possible due to Josh’s ability to work so many parts of the crew by himself. It saves on money and logistics, though demands much of his time and sanity. Their need for staff do give young creatives an avenue towards gaining experience, including a high school girl getting her first experience with sound engineering.

The advancement of technology has made this process easier as well, if not exactly easy. Star Trek First Contact had to limit its phaser use due to the $10,000 price tag of each shot, a feat that Josh can now achieve with Adobe After Effects, with motion tracking to the gun’s nozzle built in.

He has learned a ton from Avalon. “It has taught me more than I can even imagine” about filmmaking. He has figured out how to work in transporter beams and layered sounds and phaser effects, sound mixing, and become adept at organizing productions. Weeks go into the planning and preparation, most of it anticipating the inevitable mistakes that come up during a shoot. He has learned to schedule time to be off-schedule to make up for unforeseeable issues, a tactic learned from Scotty on the 1701.

Despite the investment of time and money, he unequivocally encourages you to try filmmaking yourself. “This is an act of courage and not everyone can do it. The people who put themselves out there and get something done people don’t understand how hard it is. Anyone who does that deserves praise. They have all accomplished something.” My journeys into fan films continue to prove him right. Whatever the rough edges in effects or acting, the stories shine through because of the perseverance of their creators. Which brings me neatly to…

Star Trek: Nature’s Hunger stretches the limitations of conventional fan film making eschewing the boundaries of those conventions. Its creative energy is utterly uncontainable, resulting in Star Trek crossovers with the Wizard of Oz, Silence of the Lambs, and Planet of the Apes over the course of its seven seasons. Joe Cepeda, its creator, has worn a lot of hats. He started filmmaking as a high schooler in Okinawa, but learned through fan films how far personal drive can accomplish. Pulling together amateur actors from local plays and the widening fan film community, he found in Star Trek a jumping off point towards any kind of story. Be it the trial of Dorothy Gale or battles against giant spiders, in 12 years he has created over 40 films and shows no sign of stopping now. Coordinating with other fan filmmakers has allowed Nature’s Hunger to share techniques and staff, ballooning both the size of the audience and the crews. A mixture of real and CG sets also blew open the doors of possibility, and Joe’s experimentation with technology and storytelling set the stage for innumerable more stories to come.

The films have changed over time as Joe learned more about video production. The close knit fellowship and friendship of the crew makes a huge difference, tying the community together and making ground for collaboration. Joe is a former military guy and likens the process of low budget filmmaking to battle drills, moving as quickly as possible to get more scenes each day. It is a luxury to shoot with everyone present at the same time, and one that often is not available. The proliferation of CG has made for new shooting techniques, like shooting actors at separate times and splicing them together into a single scene. Joe is cognizant that the filmmaking is not just a film, but an experience for the crew. For a crew of volunteers, there is a lot of human psychology involved in making them want to stay engaged Feeding off of their creativity and allowing it to influence the filmmaking process is a big part of what makes them invested and keeps the films creative. With more episodes coming soon, it’s clear that Joe’s imagination and grasp on human psychology are expanding over time.

Federation Files, created by Glen L. Wolfe, is an anthology series spanning ages of the setting and telling stories that would fit in nowhere else. About 8 years ago he was blown away by the quality of New Voyages, and shortly thereafter joined its crew and the crew of Renegades making props. He continued to reach out to filmmakers to offer his services, but began his own series with His Name is Mudd, first of the Federation Files. The series shows an incredible diversity of story type, partially because some episodes are made up of projects that their original creators were unable to finish.

The Federation Files shoot out of the same Harrison Arkansas as Avalon, leading to a lot of cross-pollination of cast and crew. This is useful, because finding individuals to work on these films, especially in Arkansas, is a fraught process. It takes genuine dedication to doing the work for the fun of it; fan films will never return a profit or much fame, so you know anyone putting their time into the work is doing it for the pure love of the craft. The sets have seen use in tons of other projects, including faux docu-series the Romulan War and more places than I could track down.

One of my favorites from the Federation Files is Walking Bear Running Wolf, featuring a native American character first making his appearance in the unduly ignored animated series. This story, telling the tale of a native tribe making contact with aliens, came about accidentally. Glen needed to move his sets and found a building in an abandoned amusement park, and after discovering that the owner happened to own a wolf, ideas began to flow. Six weeks later the film was shot and ready for editing. The rest of the series, planned as a 26 episode season, remains in a state of constant production.

Frank Park Jr.’s Star Trek Crossroads is just one of his many projects, including work on the Romulan War, creation of the long-running Dreadnought Dominion, as well as appearances in Raincross, Nature’s Hunger, Farragut, Constar, and more than he could remember. He recalls the post-lawsuit time as a dark one for the community, in which internal politics kept crews relegated to specific projects. The once (and now again) ubiquitous sharing of talent was nowhere to be seen, and it was more difficult to get ships off the ground. “But Vance is that type of person who is an organizer and a peacemaker.” His influence helped change the temperature of the community, grounding it in the optimism and storytelling that inspired Star Trek to begin with.

Frank doesn’t know where his next projects will lead him, only that he has no intention of stopping. “I hope to be buried in a shuttlecraft.” he said, a future that I hope comes to pass a very long time from now, well after we make first contact, if there is any justice to be had. One of his favorite features of the community is its willingness to let anyone participate, regardless of their age or whether they meet the limited standards of what official filmmaking deems an actor should fit into. The work has repaid him well, giving him experience as an actor, editor, director, and carpenter. Frank is currently working on a film titled Rebirth, with After the Fall and two-parter Romulan Ails soon to follow. For audio lovers he also introduced me to another of his passions: Filk music, a comedy/parody genre intended to sound like the type of alien music Star Trek occasionally featured. He wrote and performed Green Hills of Terra, a good introduction for anyone curious about the subgenre.

Michael Stutelberg’s Star Trek: Eagle began as a high school project but grew over time as his skills improved. A local office did a once yearly Christmas video and was selling the sets from their Star Trek themed movie. Quickly picking them up and repurposing them, Michael has been releasing a film every other year or so since 2009. Eagle is a great example of how you can watch a filmmaker grow into their own over time. From a vignette shot in a high school to longer and deeper projects, he has expanded Eagle into a powerful window to some of the more obscure aspects of the setting. With unseen gods and the temporal cold war, he has learned how much one’s limitations inform the craft. An actor is unavailable? Finish their episode with a body swap. COVID hits? Have everyone film separately. Small budget? Hook the audience as fast as possible so they want to see what the story has to offer. As a World War 2 reenactor, his access to period era costumes have spurred him to write (along with Kenneth Thompson of Starship Saladin) stories crossing over with Lovecraft and his Yog-sothothery, tying his inspirations into misunderstandings of some deep cuts into Star Trek’s lore. Eagle asks much of him, but has rewarded him with connections all over the spectrum of fan filmmakers. Because those filmmakers themselves are often Star Trek writers or cast members themselves, the reward is all the more tangible for creatives like Michael.

Joey Bonice, creator of Star Trek: Lexington, is the kind of person whose work pervades these films, whether the viewer knows it or not. His strength is in self-taught visual effects, the type of which can make or break a fan film but require specific expertise to implement. The films are a fun part of the work, but only a by-product of working together with a team of artists all of whom are constantly improving themselves and one another. “It’s a never ending constant learning process.” Working with many creators gives him unique and individualized challenges that have given him a firm grasp of visual effects over the years. Moving often made building and maintaining sets impractical, leading to the development of alternative remedies. Joey may be the first editor to integrate putting a CG into live sets in the early 2000s, a technique now a mainstay of fan films.

Lexington got started in 1986 when Joey was writing short stories on paper as TNG was getting started. He was 11-13 around then. It didn’t become a series until the early 2000s when he worked with Farragut and other projects and realized he could make something of his own. In return for visual effects on some of Vance’s projects, he helped get Lexington off the ground and into the stardock. Lexington Adventures has more work in the pipeline on its youtube channel, and you will be able to see his work and influence on other projects. Also one of the first to produce in the TOS movie era, his films laid the groundwork for the upcoming Farragut Forward, also in the Wrath of Khan timeline.

Last Minute Recommendations

If by some miracle you do find yourself wanting to delve deeper into Star Trek fan films, I have a few places you should look. There are too many of too high a quality for me to include everything on this list, but the list below represent some of the personal favorites I have encountered in my travels.

Star Trek; First Frontier. One of Captain Robert April’s first missions on the Enterprise is a heartwarming adventure with a crew you swiftly fall in love with, and improves every time I watch it.

Brandon Bridges’ Time Warp Trilogy is a monumental achievement. Written, animated, voice acted, directed, and edited by a single person, this trilogy of films (soon to see a fourth) follows several generations of a crew through time-bending adventures focusing on the burning desire to undo a past mistake.

Star Trek Farragut spans iterations of Star Trek, from the original series to animation and soon 80s-era movies with Farragut Forward. Star Trek Exeter has only a few episodes, but each of them are wonderful stories.

Star Trek Antyllus is a little rougher around the edges, but if you can get past some simplistic visuals and appreciate the story for what it is, you’ll get some of the best-conceived, morally conscious science fiction out there. Don’t miss George Kaiyan’s trilogy of films either.

For those interested in audio dramas, you can’t do better than Outpost and Excelsior. Outpost tells the story of a long-neglected station slowly building itself into galactic relevance, and Excelsior picks up on dropped plotlines from prior series to tell an epic tale of war, espionage, and the morality of maintaining a stellar civilization.

Anywhere you go with Star Trek fan films, you’ll find something to reward the chance you’ve taken. What’s important to understand is that these projects, whatever their budget or tone, exist right alongside each other. It isn’t that different when you consider that courtroom drama, horror, and fantasy exist right alongside each other in the ST franchise itself (or did you forget that time the crew of the Enterprise met the devil and learned to do magic?) The fan film continuum is made of people working with one another and contributing to each other’s works directly. It isn’t a hard continuity, but in its willingness to accept anyone enthusiastic enough to join, the Star Trek fan film community lends legitimacy to anyone who wants it. Existing right up alongside the bigger projects, which more often than you would expect involve original actors or writers from the series, lets people be a part of the adventures they dreamed of for so long. Whatever general audiences think, these works continue to see funding and production. They persevere for the love of the art, and that love shines through in every short, film, or series.

Click For More Articles in the Fandom Underground series