Sword and Sorcery sits at a tenuous place in the popular consciousness. While people generally consider it to be underappreciated, the genre keeps getting entries and new adherents. It really feels like it’s constantly cresting the wave of some upcoming resurgence, when finally we can all admit to ourselves that it is and always has actually been good. Suffer, an independent S&S film from writer/director team Kerry Carlock and Nicholas Lund-Ulrich, examines another aspect of the genre that is often misunderstood: its treatment of women. This comes at an interesting point, with action-heavy Red Sonja and Deathstalker releases earlier in the year, leaning into the fun without as much weighty consideration of the things being depicted.

Sword and Sorcery is often decried as cheap trash, but the truth is more complicated. The iron thews of Conan, first described in pulp magazines, belied a thoughtful owner and literature with the intelligence to stand the test of time. Sword and Sorcery is a deeply cynical genre, with a lot to say about the distribution of power. It leans into a fresh, hostile world where human society is a vulnerable but burgeoning thing, a fact that may not be for the best. I’ve talked about it before with Indie TTRPG Defy the Gods, and how its oppositional forces of law and chaos point out the injustices we allow in society. The incompetent, unworthy men who we protect from consequence and give more power to. The kinds of people you can immediately spot as narcissistic conmen who rise through the ranks by cheating and violating every code of the civilizations that support them.

Women exist in a complicated place within this context. Ostensibly, the harsh world of the past sees them as disposable, weak objects. But these are modern sensibilities, not ones that come from a real view of ancient societies. Robert E. Howard was encouraged to include scenes of ladies clad, but scantily, contorted on a series of altars. Doing so would inevitably be included on the covers and give his story top billing. But that cheap trick to sell the tale also forgets a more nuanced view of female characters, in a time before many rigid gender roles could take form. There are more and better representations than these, and even Conan himself changed views over time. The Frost Giant’s Daughter even sees his younger self trying to commit sexual assault. His final lines in Hour of the Dragon, however:

Conan stood silently watching the priest as he went. From various parts of the field knights were hurrying toward him. He saw Pallantides, Trocero, Prospero, Servius Galannus, their armor splashed with crimson. The thunder of battle was giving way to a roar of triumph and acclaim. All eyes, hot with strife and shining with exultation, were turned toward the great black figure of the king; mailed arms brandished red-stained swords. A confused torrent of sound rose, deep and thunderous as the sea-surf: 'Hail, Conan, king of Aquilonia!'

Tarascus spoke.

'You have not yet named my ransom.'

Conan laughed and slapped his sword home in its scabbard. He flexed his mighty arms, and ran his blood-stained fingers through his thick black locks, as if feeling there his re-won crown.

'There is a girl in your seraglio named Zenobia.'

'Why, yes, so there is.'

'Very well.' The king smiled as at an exceedingly pleasant memory. 'She shall be your ransom, and naught else. I will come to Belverus for her as I promised. She was a slave in Nemedia, but I will make her queen of Aquilonia!'

Truthfully, S&S is not progressive or regressive, in the traditional sense. It supports reexamining our responsibility as individuals within societies, and doesn’t allow us to blame a nebulous group or philosophy or religion for our own decisions. The reactionary elements of the American right ignores the genre's willingness to examine those assumptions. Hyperborean fantasies about the strength of our forebears ignores so many things about the brutality and ignorance of the peoples being depicted. They ignore that the concept of race as we understand it now didn’t exist until recently.

Red Sonja may be the most prominent example of female representation, but it isn’t the best. I’m a red blooded American man and I can appreciate the visuals for what they are, but the fact is that C.L. Moore and her Jirel of Joiry stories remain the better work. Red Sonja’s 2025 entry is…fine? I don’t have particularly interesting things to say about it. Its story is acceptable. It has a plot which is inoffensive. The aesthetics generally work. They don't give me anything to chew on the way Moore did. Catherine Lucille Moore had to go by her initials to hide her gender from publishers who would otherwise reject her work. She is one of many writers to use this tactic, like Star Trek’s luminary D.C. Fontana. Jirel, along with Moore’s other work, features stories carefully examining power dynamics, addiction, trauma, and revenge in a package of fantastic, high concept fantasy. These struggles and stories ring true, and are gaining more credit as time goes on.

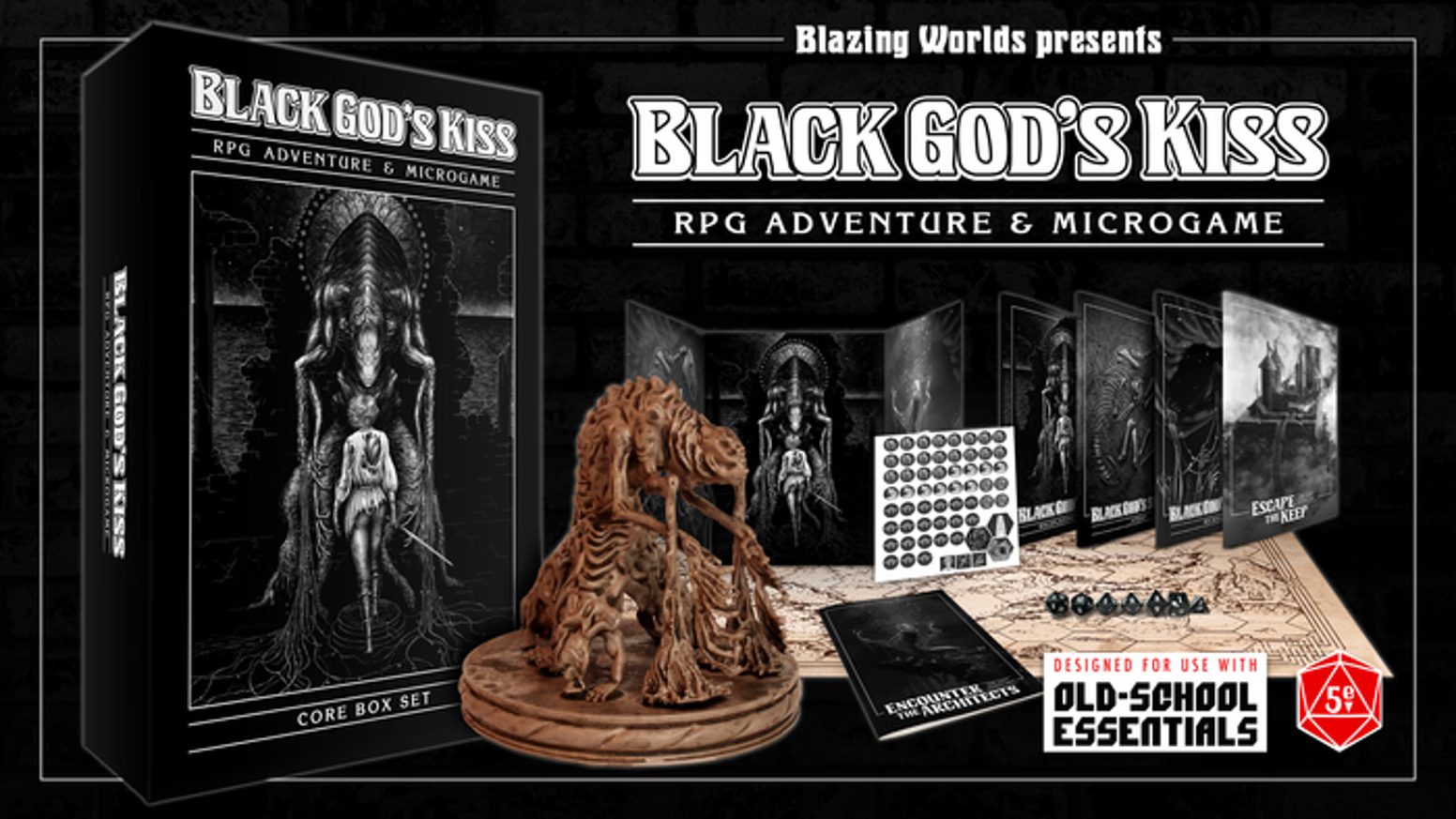

Jirel is best known for The Black God's Kiss and its follow up The Black God's Shadow. In these stories, she is assaulted by a warchief and ventures to a dark underworld to seek a power that would help her achieve vengeance. What she finds is a success greater and more terrible than she bargained for. Seeking revenge in a violent way, a way that reads as male and derivative of the war chief's sin, ties her to him. It taints her soul, shackling her to that sin and the things she did because of it. Women, Moore seems to suggest, cannot excel if they acquiesce to the structures and mindsets that bind them in the first place.

That leaves us with some...odd options to explore in the modern day. She is Conann is insanely imaginative but kind of incoherent, something the creator talks about with pride (as attested to by his Incoherence Manifesto for filmmaking). It depicts female warrior Conann venturing forward in time, as many actresses take on the character experiencing desperation, loss, and finally independence in a a series of connected settings. Bertrand Mandico’s films examine femininity with a kind of earnestly ignorant Frenchness that is infinitely entertaining. It’s poorly informed and voyeuristic, but this and After Blue take to their respective S&S and science fiction plots with such elaborate, dreamlike production design that you can’t help but stay engaged.

Mandico's films, along with the practical effects of 2025's Deathstalker and Suffer itself, succeed largely because of the tactility of their spaces. Production design is the watchword of good Sword and Sorcery. They help deliver the feel of a real, lived in space, with its own recent history and forming cultures. Having done a quick look through the film's many influences and contemporaries before diving into Suffer, I found myself consistently impressed. Sword and the Sorcerer by Albern Pyun looks better and has a more interesting story than I was ever lead to believe. It exemplifies the granularity of 80s production design. This worked well because the genre is supposed to be some variation of low fantasy horror, with real people and societies at stake in smaller scale stories. Dragonslayer might be the king of this dark, threatening fantasy, but there are plenty of examples from the 80s. Neverending Story, In the Company of Wolves, and most of Terry Gillian's career show this work in other contexts.

Suffer, taking a step forward

All that brings us to the modern day with Suffer. The film depicts its two forces of nature and civilization in physical, psychic, and visual conflict. When a prince, servant of a dark outer god, magically silences all opposition with horrendous mechanical masks, liberation seems impossible until a lone warrior begins gathering help from disparate sources and shattering the power structures that keep the prince's magic in place. Elements of the metaphor may not be subtle, but the visuals more than complement this story.

Realizing that independent fantasy epics are an effort in masochism, the team knew that they could only succeed if the film's aesthetics matched its conceptual grandeur. Released at the tail end of 2025, the film shatters expectations for a $30,000 budget. Its lead team have been longterm creative and romantic partners, and the film itself is a blending of opposites. Its exteriors are majestic, awe inspiring, and threaten the idea that we as human beings have any real control over the world. The interiors, by contrast, are artificial, cramped, and overhung with the darkness of the god that lends its power to the Prince.

Once again, we find a COVID project spurring intense creativity: how does one shoot something outside, with masked characters, who must stay apart from one another? Suffer is the answer. The natural scenes of journeying around the kingdom were all shot in Idaho at the end of 2020, sometimes amidst two feet of snow. The castle set is VFX, posing its restrictive regime as something inherently indecent and unnatural to the human animal. It's a desolate, dispassionate place which is completely at odds with the broad world outside. This deliberate framing melds perfectly with a later scene of psychic assault, in which the two aesthetics meld together, fighting in a conflict over the character's mind and our focus.

This kind of intentional design is far more effective than the shameful, lazy work that was The Reign of Queen Ginnara. That film used AI generated creatures, effects, even entire scenes, and every second of them was horrendous. Not only that, the way they clashed with the rest of the film only made the filmed sections look worse, all while running the movie to two and a half hours. Despite some incredible sound work like the chanting theme of Ginnara herself and more than a few genuinely wonderful shots, the thoughtless and garish AI in the film makes it a menial embarassment. I enjoyed Lawrie Brewster's Slave and the Sorcerer despite some hiccups in the delivery, but I can't justify staying with British Horror studio any longer if it's going to compromise its work so thoroughly as this. For shame.

Where most Sword and Sorcery films lean into a Tolkien/medieval form of fantasy, Suffer is far more of a western. Its costume design, music, and broad frontiers speak of the boundless yet uncontrolled future waiting for humanity. There is something comforting about how this vast place, even in its disregard for humanity, is somewhere we belong. The clinical, right-angled, neon-lit castle is the opposite. It and its authority are an imposition on those ideals. Fundamentally the idea of an enforced hierarchy where men in crowns have the right to control women is not what exists in the natural world, where one person is as vulnerable as circumstances allow.

There was a further goal for the film, playing off of Moore's original takes: making sure the hero didn't succeed along traditional male lines. Having her win alone, by violence, speaks only to the strength of one person's arm. The resolution we find in Suffer is more complicated and more collective than any battle could be. Killing the Prince, after all, does nothing to upset the structures that put him in place or kept him there. The fate he receives is not so simple, nor is the world we inhabit today.

The care for practical effects and weathered clothing speaks to how much you can accomplish with talent despite having a low budget. Those accomplishments, held up against limited resources, continue to mount as I look back on the themes and their delivery. The lack of time and closeness they would need for fight choreography translates to a story about how one person can't be sufficient to win a revolution. It doesn't matter how strong you are or how many people you kill; a popular movement of the people needs the support and presence of those people.

It bears saying that Carole Jones' work as costume designer, Joanna Karselis' score, and April Frame's cinematography did immense work to give this film the feel and tone that it conveys. All of their strengths are maybe best conveyed in the opening shot. It's a long, slow sequence telling you all you need to know about this world and how badly our main character is on her back foot. The action that ensues is vicious without being gory or campy, due in no small part to Stax' performance as the Plague Knight, hounding her throughout her journey. The sound design of the masks keeps carrying you into the world as well. The bearer's screams are silent, haunting us with their absence but mirrors how distant the characters feel when shocked with bouts of pain. At the same time, we don't hear the kinds of screams that would cater to an indecent interest in watching people, well, suffer.

There are a few things in Suffer that didn't work for me, but all of them are spoilers for things key to the film's plot. If you have any interest in pursuing this film, you can find more at the Dosgoats production page, or rent on Amazon Prime Video or iTunes. Moreover, the team will soon be releasing more details of the setting in an RPG book, featuring some inventive rules around silent roleplaying for temporarily masked characters. I'm interested in where the creative team takes their work, and what genres they explore next.