There’s a general misconception that the stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—are linear, progressing from one to the next until you inevitably internalize your loss. Even Elisabeth Kübler-Ross herself, the first to observe and publish her findings on the grief process, originally believed that these emotions happened in sequence. She eventually came to understand her own model differently, acknowledging that some people had been observed experiencing multiple stages at once, or skipping stages entirely. In truth, there’s never been any scientific evidence to back up either her initial or revised claims. And yet, since these supposed stages have been so well-documented in the nearly six decades since Kübler-Ross first published her findings, it’s hard to say that it hasn’t become a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. This is how we grieve now.

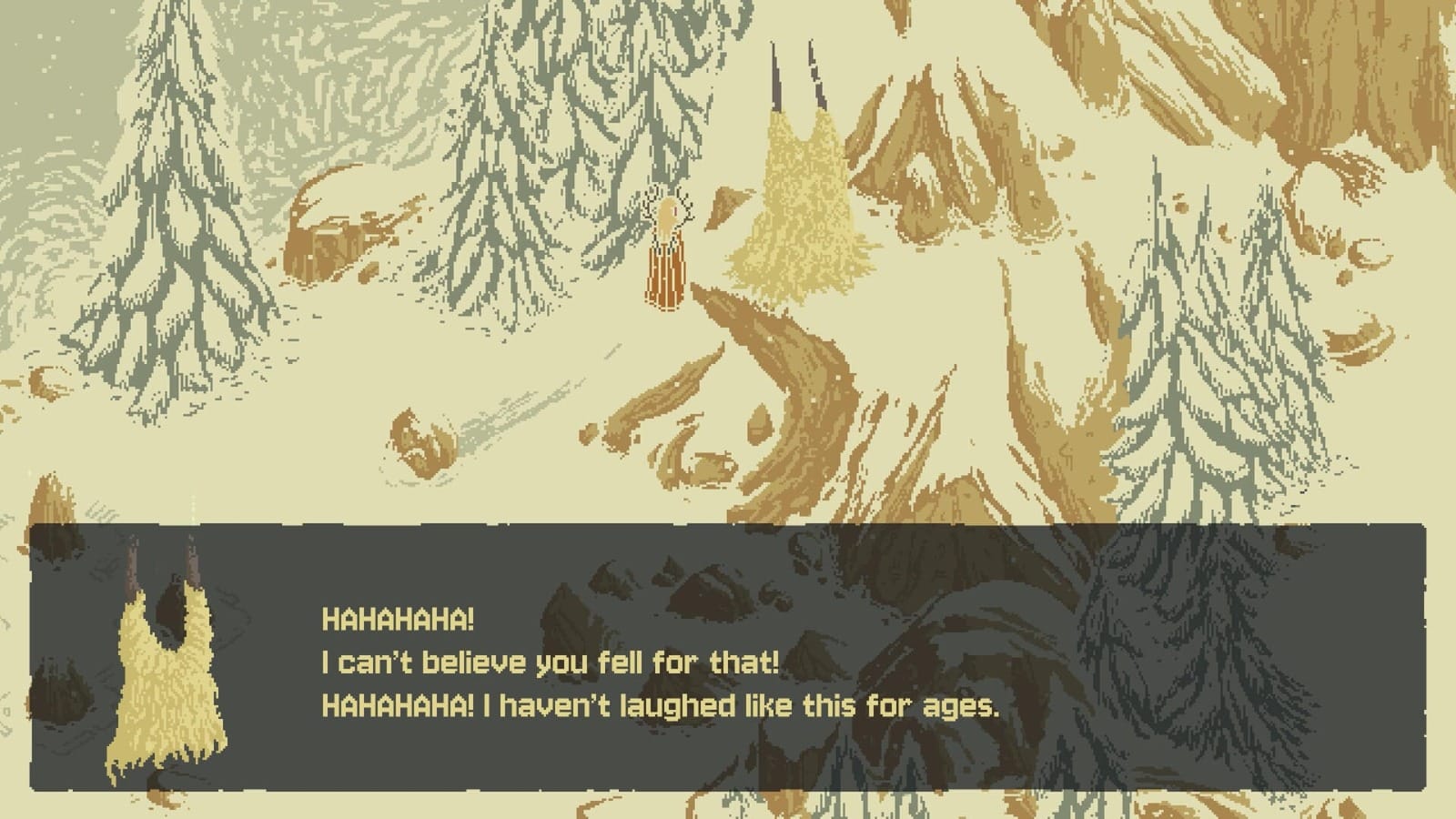

Death Howl suggests that this is how we’ve always grieved, since our first tribes formed. To grieve so strongly is part of what makes us human; would any other mammal so badly desire another day with their lost son, that they ventured to the spirit world just to find him? The game has you play as Ro, a mother living in Southern Scandinavia during the European Mesolithic age (about 6000 BCE), who is consumed with pain and guilt after the tragic death of her dear infant child. Though not a shaman, she wills herself into the spirit realm, guided by a majestic moose who feels a connection to Ro. He instructs you to free the four Great Spirits, each afflicted with a mask that’s causing them a different form of anguish. It becomes clear very quickly that these Great Spirits’ masks represent the first four stages of grief, and, true to Kübler-Ross’ later amendment, they can be tackled in any order you wish.

The world of Death Howl is brutal but beautiful, like if Blasphemous were more keen on awing you than grossing you out (though some Death Howl bosses are rather grotesque). The pixel art is minimalistic outside of combat, with no HUD and a different uniform colour dominating each of the game’s 13 areas. The locations are your typical video game biomes (snowy, forest, desert, etc.), though they’re infused with a mournfulness that makes each feel serene but distant, like you aren’t quite meant to be there—you’re trying to uproot the natural order of the world, after all. In combat, things may look overwhelming if you're less familiar with the traditions of the genres at play, but the game does a decent job of maintaining visual clarity even when your hand is full of vibrant cards and the battlefield is littered with gnarled enemies.

To begin discussing what the gameplay is, let’s talk about what it’s not: Death Howl isn’t a roguelike and, controversially, I don’t think it’s a soulslike. The roguelike absence is only notable since deckbuilders are so often associated with the genre; they’re nearly inextricable from each other. Death Howl sets itself apart by allowing you to develop four different decks over the course of each zone, gathering supplies to craft cards and choose how you want to approach fights. Once you have a card or totem (this game's version of slottable passive buffs), you’ve got it for good.

Death Howl is a self-described soulslike. As in, it’s right below the game’s title in all its trailers. I think this is buzzword abuse, and I say that as someone guilty of constant buzzword belligerence. Though there isn’t some textbook definition of the genre, I have to imagine that a turn-based deckbuilder is categorically eliminated from soulslike eligibility. Points for: enemies respawn when you rest. You can recover lost XP by beating the enemy that killed you. You can explore a non-linear semi-open world. The game can be quite punishing. Points against: it’s a turn-based tactics game, not an action game. You respawn immediately before your last fight when you die. There are few, if any, RPG elements. Now that I’ve laid it all out, I see the case if I squint. But I can’t get over the fact that the game is played in a fundamentally different way than any other game even remotely considered a soulslike. Does this actually matter? Absolutely not. This has no bearing whatsoever on my thoughts on the game as a whole; I just found it to be a tiny marketing annoyance that bothers me far more than it probably should.

The gameplay can be summed up with some easy comparisons: it’s Slay the Spire's cards meets Into the Breach's grid-based combat, with a structure not dissimilar to Inscryption’s second act. After a brief tutorial, you ostensibly have the ability to enter a handful of different areas. Actually accessing those areas, though, will likely prove more difficult than it’s worth until you’ve unlocked more cards and passive items. There’s a nice open-zone structure, but it serves more of a subtle narrative purpose than a tangible gameplay one. You’re most likely going to complete each zone entirely before moving onto another one, and the permanent abilities you gain upon completing an area are minimal but noticeable enough that your last zone will likely be your easiest.

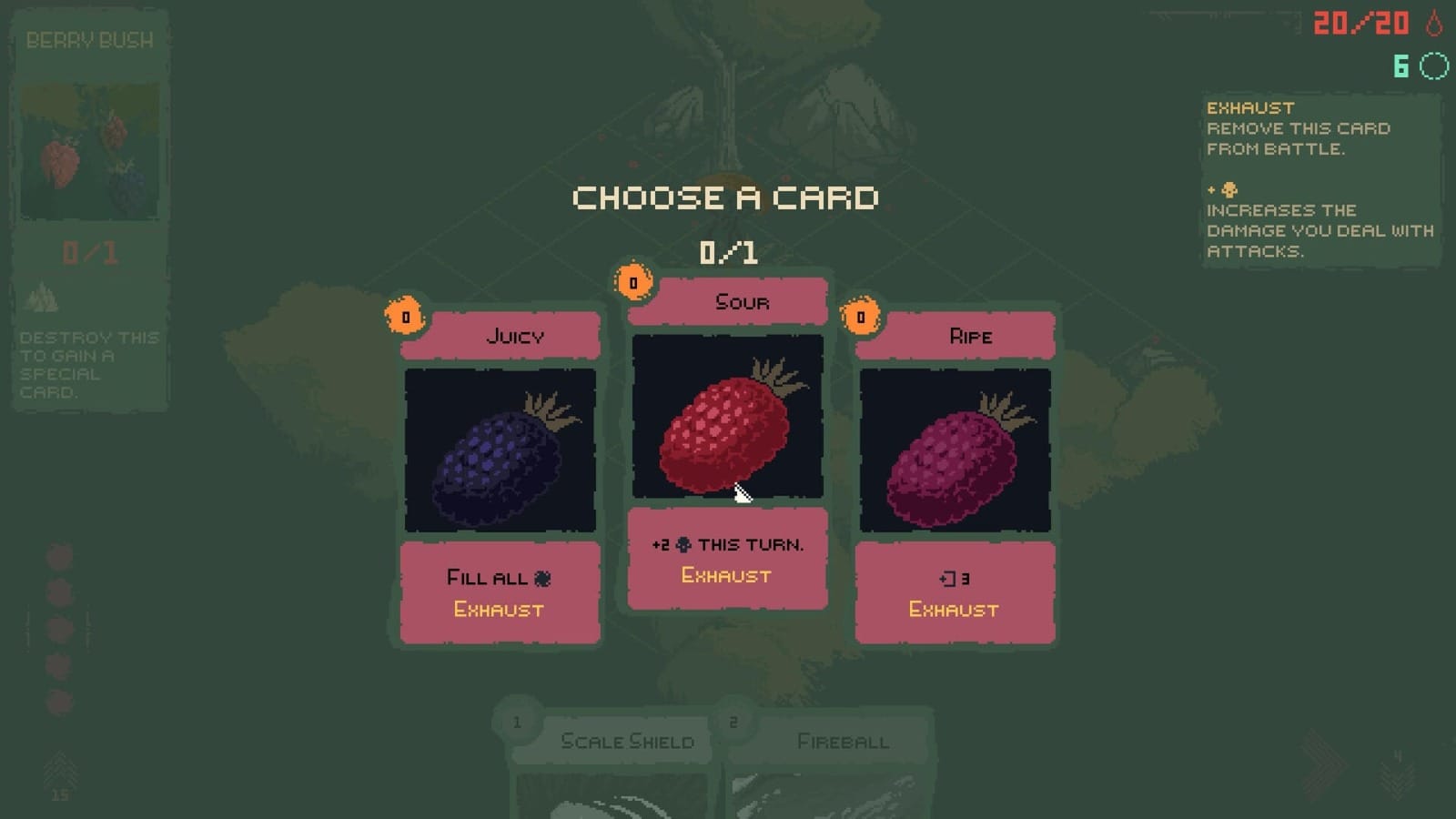

Traversing the world requires tight health management, as you’ll frequently encounter enemies to fight along your path. You’ll draw five cards each turn and will use said cards to attack, block, outmaneuver, and outsmart your strange opponents. You will not heal at the end of battle, and will often have to engage in at least a few bouts of deadly fisticuffs before reaching another checkpoint. There’s an element of risk/reward as well; I found that there were plenty of times when I avoided relaxing at a newfound rest spot to make sure the enemies I’d downed along the way stayed gone a little while longer.

Dying will respawn you at the beginning of the fight you failed, with the same amount of health you entered with, so you have to be economical as you get through each fight lest you finish one with 3 health and leave yourself with no hope of continuing onward. This has the potentially unintended effect of encouraging repeated restarts of fights that don’t go your way—even ones that you’re about to win—and abusing the RNG system, which can swing wildly from one extreme to another.

Cards that draw more cards are difficult to come by and relegated mostly to the first area, making your hands occasionally feel unluckily underpowered. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; sometimes a bad hand can build tension and force you to improvise or find creative ways to avoid massive damage. You can fill your deck with anywhere from 15-20 cards, so if your deck is feeling inconsistent, there is some room to thin it and draw that perfect combo more often.

The fights themselves are beautifully animated bouts of predictable enemy patterns and energy management. Unlike Into the Breach, you’re only controlling a single character, which makes battles more focused. You likely won’t find yourself spending 20 minutes on a single turn finding the perfect order to play your cards, but there’s still a significant amount of strategizing required to get through unscathed. Enemies have simple movesets, but don’t indicate precisely what their next move will be, forcing you to adapt to any possibility. This deviance from the Into the Breach/Slay the Spire structure of providing full enemy information is a double-edged sword: sometimes it makes the game feel more satisfying as you gradually learn how to manipulate each enemy type differently, other times it feels like a frustrating guessing game.

The four zones each have a bespoke deck that you unlock cards for as you progress. A couple unique mechanics populate each deck, often working together to give them a fun identity. The cards themselves aren’t massive deviations from what you’d see in other deckbuilders (you have your discard builds, HP sacrifice builds, poison builds, etc.), but they excel at enabling glorious combos that make you feel like a card-combo-ing god. The balance is decidedly off, though. Some cards are simply far too underpowered to be functional, dwindling the decently robust card options down to a core set that are a clear best choice, with a few elective cards that can be slotted in. I believe some balance patches have been released since I beat the game, so this may have already been fixed to some extent.

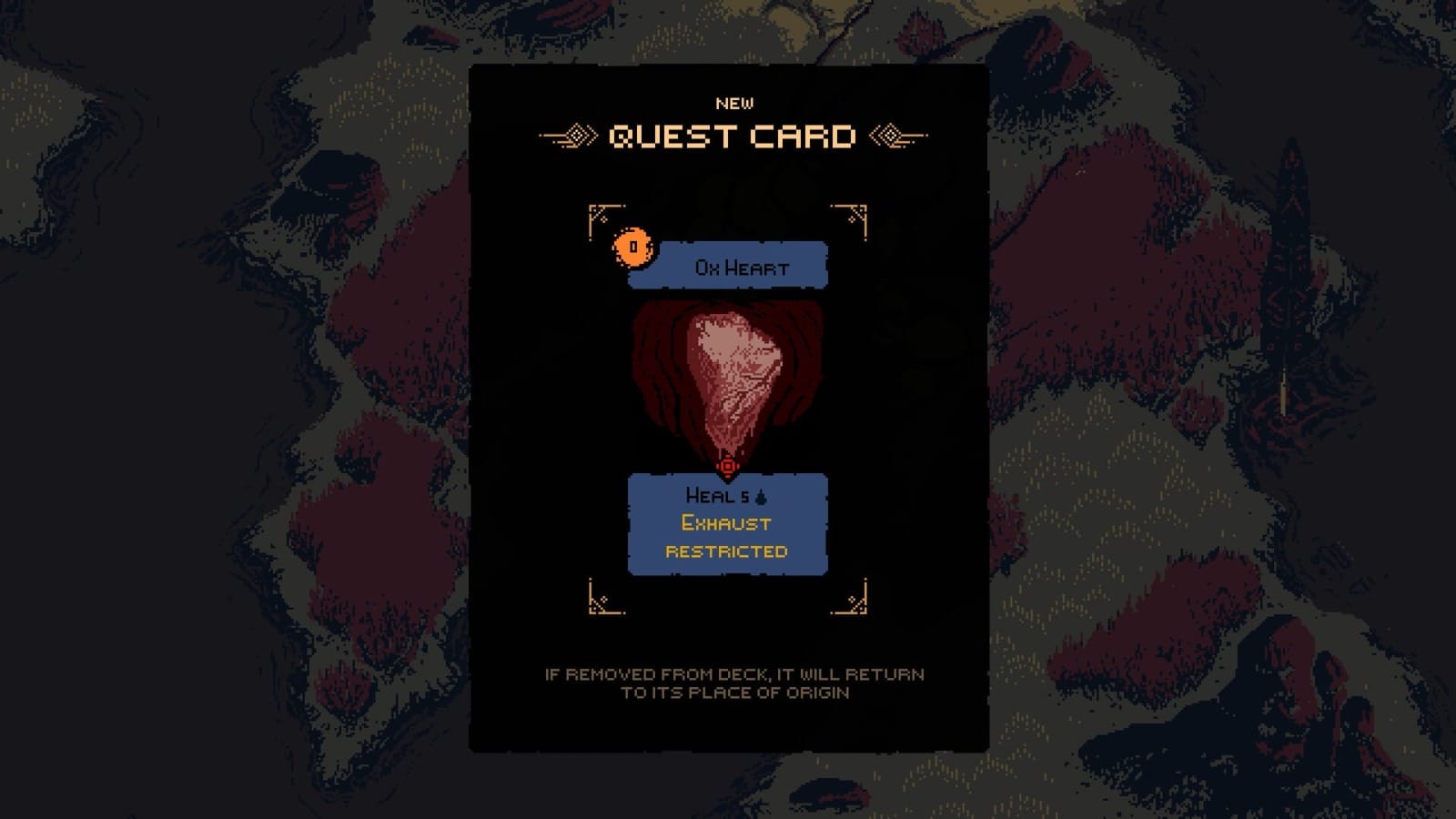

Side quests are the game’s most questionable offering. I see the vision, but I think the execution lacked foresight. Most side quests—often given by eerily majestic afterlife denizens in need of help to move on from a source of tragic anguish—are simply not worth finishing. Many of them require that you add quest cards to your deck, which are often minor burdens, though some are interesting boons. It’s a compelling idea that has you trading away power temporarily in exchange for a later reward.

The problems arise as soon as you open your map and attempt to travel to your new quest marker… and find that you can’t. Fast travel is disabled while you have a quest card in your deck. At this juncture, you can either quit the quest, leaving the card where you found it, or you can pursue the quest in its entirety, effectively being locked to the quest for the foreseeable future. This wouldn’t be so troublesome if the quests weren’t lengthy, difficult, and worst of all, unworthy of all your time and effort. Too many times I completed a gruelling task only to receive an item I would never use. This would be more excusable if the quests contained some intrinsic reward in the form of additional story or lore, but they’re largely devoid of that, too.

Death Howl is a lengthy game, but one that rewards your perseverance more often than not. Its ending feels inevitable to the player but inconceivable to Ro, making her journey feel all the more heartbreaking but motivating nonetheless. Though the game’s balance and optional content leave the game in a less than perfect state (not to mention a handful of annoying bugs, one of which robbed me of an hour’s progress), the innovation of its gameplay systems and the vibe of its world are worth experiencing. You may deny its difficulty at first, rage quit, return it to Steam, buy it again, realize you’ll never beat it and nothing matters, but eventually push through all the adversity to reach Death Howl’s bittersweet acceptance. Not necessarily in that order.

Death Howl

Great

Death Howl is more than just a saturnine Into the Breach meets Slay the Spire with a semi-open world twist. Okay, it’s not much more, but is that combo not intriguing enough on its own? Combining two masterpieces may not have begotten another masterpiece, but this is a noble attempt.

Pros

- Beautiful pixel art and animations

- A simple but moving tale of love and loss

- Great choices for obvious inspiration sources

Cons

- Long side quests with lacklustre payoff

- Questionable balance

- Some immersion-breaking bugs

This review is based on a retail PC copy provided by the publisher.