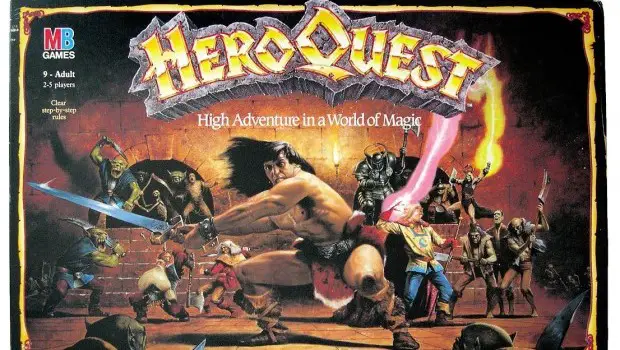

While several developers have tried to create projects that commemorate or honor games from the past, they often have found themselves working for nothing because of a cease-and-desist order. While that happens more frequently in the video game universe, a unique case has come to the board game world. The 25th anniversary of HeroQuest is this year, and a company is trying to create a version of the game to commemorate it. However, they have tried to crowd fund it and have been rejected a couple of times due to the rights. Mike Selinker is a game designer who has made his opinion known, and I asked him nine questions to go further in depth about the subject and get a better understanding about the issues involved.

What kind of background do you have in gaming?

I’ve been a game and puzzle designer since I was 15. I was a freelancer through college, and later became a full-time designer. I’ve worked for Wizards of the Coast and Paizo, both as a creative director and a game designer. I’ve designed, co-designed, and/or developed games like the Pathfinder Adventure Card Game, Risk Godstorm, Unspeakable Words, Lords of Vegas, Axis & Allies Revised, the Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game, and Betrayal at House on the Hill. I also was a creative director on 3rd edition Dungeons & Dragons. In 2003, James Ernest and I founded Lone Shark Games, a small design studio in Seattle, which I’ve run for eight years. I go to a lot of game conventions and play a whole lot of games.

Do you have any connection to HeroQuest?

Not one bit. I barely recall how to play it. When I was working for Hasbro, I can’t remember the game coming up much at all. I occasionally help Hasbro with their events, but I haven’t worked as an employee there for over a decade. I do not speak for them in any way, and have not heard anything from anyone there about Hasbro’s take on the situation.

I should say I’m not claiming any legal expertise beyond my experience with game design contracts. This is just my opinion. I made a post on BoardGameGeek about it, and it was shared all over the place, not coincidentally because a lot of game designers and authors are scared about the possible impacts of these developments.

What was your reaction when you heard about the HeroQuest 25th Anniversary project?

When I first saw it, I reacted very negatively. I’ve seen a fair amount of crowdfunding campaigns that bring back ancient games; some great ones include the return of Space 1889, Ogre, and Torment. But this one looked suspect from the get-go. None of the people I would’ve expected to be associated with HeroQuest—Hasbro, Games Workshop, designer Stephen Baker—were on board. I concluded that this was a questionable campaign at best, and at worst an intentional misrepresentation of the rights status of the game. When it got booted off Kickstarter, I thought that was the end of it. When it then got booted off Verkami, I thought that was the end of it. But then when it resurfaced on Lanzanos, I became convinced that Gamezone was going through with this no matter what, and that people would back them no matter what. This despite the fact that they haven’t shown any evidence that they have the rights to print the game in English.

Why do you think that the HeroQuest 25th Anniversary Edition poses a threat to game designers?

We designers rely heavily on the expectation of the marketplace that what we do is original. But Gamezone is attempting to publish a game that they did not design and do not appear to have the English-language rights to; it’s very unclear whether they have any rights except maybe the ability to use the name in Spain.

My fear is that if this goes through, we’re going to see other companies take runs at IPs they don’t own, and people will look at this campaign as a watershed for the co-opting of game IPs. I don’t want people to feel they have the right to publish their own versions of games I haven’t released into the public domain. And I don’t want them to have this campaign to bolster those feelings.

What kind of risks do supporters of the Gamezone Project face?

That is hard for me to judge, since Gamezone hasn’t released any rules that make me confident that this is indeed HeroQuest. Either it’s the same game, and that means it might be theft, or it’s a different game, and that means it might be fraud. I don’t understand how anyone can sign up for either of those. And whatever you think of the legal issues, the ethics have got to bother people.

It’s tough for me to decide which would be worse: if Gamezone is prevented from following through on their obligations, eroding people’s faith in crowdfunded games, or if Gamezone isn’t prevented from following through, in which case they’ve set a dangerous precedent that could affect designers like me for a very long time.

What are the issues surrounding the IP of HeroQuest?

It’s pretty complicated, and I don’t presume to understand it completely. Hasbro and Games Workshop created the game, and I don’t know if Stephen has some connection to the rights. (We know each other a little from when I worked on Avalon Hill, but haven’t talked about this.) The trademark status of the name seems to have fallen away from Hasbro, and game designer Greg Stafford has a claim to the Hero Quest trademark and has licensed it to Moon Design for a game set in Glorantha. I have no idea what happened in Spain, but it looks like the authorities there have awarded the naming rights to Gamezone or someone close to them. That alone does not entitle them to the game, especially not in English, a language in which they’ve promised to release the game.

Some fans contend that since Hasbro hasn’t done anything with the game in years, it should be open season on the rights to the game. That’s insane. In the US, copyrights extend for the life of the author plus 70 years, and for works of corporate authorship to 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication. You don’t have to like that law, but it is the law. That’s what people like me need to keep paying our bills, and later those of our heirs.

Is there anything that could be done by Gamezone to provide good faith to the designers?

You’d have to ask Stephen or someone else at Hasbro about that. To me, I would love to see some proof that someone has officially transferred the rights of production to Gamezone, rather than Gamezone just squatting on it. I would love to see Hasbro or Games Workshop back them up. Maybe that’ll happen, and maybe it won’t. I hate to presume bad faith, but after they’ve been ejected from two funding sites for IP disputes, I can’t presume good faith either.

I also want to see some action from Lanzanos. This project is already an order of magnitude larger than most other projects on the site, and they stand to make a lot of money from it. So are they going to look at Kickstarter and Verkami and think, “We want to have standards like those guys,” or will they think, “We’re the place where anything goes”?

Do you think there would be less animosity if Hasbro wasn’t involved?

Hasbro is no one’s sympathy magnet; it wasn’t when I was there, and it isn’t now. But that shouldn’t affect anyone’s opinion. A victim is a victim. It doesn’t matter what you think of them; it only matters that they were victimized. This is not a little David taking on a big Goliath; it’s one company appearing to decide that the other’s rights don’t matter.

Hasbro’s not a monolith, either. It’s composed of hardworking people, and some of the best game designers around. I have lots of friends at Hasbro, and I get pretty defensive when my friends are attacked, even as indirectly as this. And of course, it’s not just designers. Lots of people worked on HeroQuest all those years ago—artists, sculptors, editors, brand managers. They deserve better than to have their hard work pirated like this.

There’s also a serious question of brand identity. If this goes through, then Hasbro will have problems in the marketplace if it decides to ever do something with HeroQuest. Especially if Stephen, who’s still there, decides he wants to. Shouldn’t he have that right above everyone else?

And of course, it’s not just Hasbro. If this works, what prevents someone from getting the naming rights to any game in another country and putting out a pirated version of that game in English? This isn’t the Wild West. We need our protections to matter.

What, in your opinion, can designers do to ensure something like this doesn’t happen in the future?

Well, they can speak up against abuses of the system. That’s a start. But we may have to start putting walls around our designs, making it crystal clear who owns what, and who is not permitted to do anything with it. Our income streams are based on companies believing they have to pay us for our creations—the belief that we can make something, sell the rights to someone else, and then make an income off the sales of that item. If that confidence goes away, we might as well stop making games. I think everyone loses under that scenario.

So if you’re backing the HeroQuest game on Lanzanos or in any other forum, I hope you’ll take a hard look at the message you’re sending to designers like me. I’d like to keep doing this for a long time, and it’s your encouragement which makes it possible.

While not working as a Database Administrator, Keith Schleicher has been associated with Gaming Trend since 2003. While his love of video games started with the Telestar Alpha (a pong console with four different games), he trule started playing video games when he received the ill-fated TI-99/4A. While the Speech Synthesizer seemed to be the height of gaming, eventually a 286 AT computer running at 8/12 Hz and a CGA monitor would be his outlet for a while. Eventually he’d graduate to 386, 486, Pentium, and Athlon systems, building some of those systems while doing some hardware reviews and attending Comdex. With the release of the Dreamcast that started his conversion to the console world. Since then he has acquired an NES, SNES, PS2, PS3, PSP, GBA-SP, DS, Xbox, Xbox 360, Xbox One S, Gamecube, Wii, Switch, and Oculus Quest 2. While not playing video games he enjoys bowling, reading, playing board games, listening to music, and watching movies and TV. He originally hails from Wisconsin but is now living in Michigan with his wife and sons.

See below for our list of partners and affiliates: