Do you like gathering around a table (real or virtual) and chucking dice with your friends? Do you like smacking zombies in the head? Making bandits regret attacking your town? Hunting down dragons and claiming their horde for yourself? Ending the plans of evil-doers and being hailed as heroes?

Of course you do, those things are awesome!

You know what’s less awesome? Waiting five minutes for your turn, finishing in fifteen seconds, and then having to wait another five minutes to do anything. Getting knocked out just before your turn, healed back up, then downed again before getting to take your next turn. Wanting to chase down the bad guys now, but the cleric and the wizard are out of spell slots and need to long rest first. Knowing that they had to burn those spell slots because you failed to hit anything last combat. Having the perfect spell planned only for the battlefield to suddenly shift and now you need to re-read all your spells and pick a different one while the rest of the group waits for you.

Well, now there’s a game that can give you all of that awesome and none of that less-awesome, and that game is Draw Steel. But before we get into what Draw Steel does, here’s a little bit of history so you can understand why it does those things.

Draw Steel is a heroic fantasy TTRPG by MCDM Productions. MCDM was founded by YouTuber Matt Colville as a publisher of 3rd-party content for 5th Edition D&D. Matt himself is perhaps the most famous “DungeonTuber” thanks to his popular Running the Game video series. Many episodes of Running the Game would be the inspiration for MCDM products, and to a small extent that includes Draw Steel.

Between the crowd funding campaign for MCDMs most recent (and presumably final) 5E supplement, "Flee, Mortals!", and its actual release, there was an industry shakeup. If you haven’t heard of the “OGL Scandal”, just know that in January of 2023, Wizards of the Coast released proposed changes to the 5th Edition Open Gaming License. These changes would have devastated most 3rd-party publishers, and MCDM was no exception. While WOTC walked back the proposal, all 3rd-party publishers faced a choice: continue existing at least partially at the whim of another company or make their own game they control the license for.

Obviously, MCDM chose to make their own game. However, while the OGL scandal kicked things into high gear, it’s fair to say that they were already thinking in this direction. Many MCDM products were already being made to shore up various weaknesses in 5E. The monsters' rules for "Flee, Mortals!" was itself an attempt to adapt D&D combat into something more interesting, and several Running the Game videos were focused on working around things that are almost fundamental flaws. D&D today is largely a heroic fantasy game, but it’s still dragging around mechanics for ways it used to play. Maybe the solution is to throw it all away and start fresh.

So that’s what they did.

Draw Steel takes a look at current heroic fantasy and works hard to strip out everything that doesn’t make sense or slows things down. In this, it pulls a fair bit of inspiration from D&D 4th Edition. It’s got plenty of new things to add, too. Ability scores now are the modifier. No need for special dedicated healers, anyone can heal themselves and plenty can help others heal. No spell slots or short rests or need to memorize how dozens of spells work.

How it all works

Let’s talk about specific mechanics. In Draw Steel, you only really need three dice: two d10s and sometimes a d6. Its most obvious divergence from D&D—or really, most other games—is that there is no roll to hit. Instead, you roll 2d10 to see how effective an ability and its secondary effects are on a chart with three outcomes. You might not get the result you hoped for, but it always does something. The second biggest change is the concept of Heroic Resources. Each class has its own Resource, always gaining some when it’s their turn and when certain things happen in combat. Those resources are then spent on the big splashy moves every class has. In other words, as the fight goes on the heroes get stronger, not weaker. And since the resources are lost at the end of combat, there’s no reason not to spend them.

After those two things, there’s a ton of little, more subtle things that build on that foundation. As players win fights, they gain Victories. Each Victory grants you one heroic resource at the start of the next combat, until you take a Respite, at which point the Victories become XP… and Recoveries reset. Healing is done via these Recoveries, where a Recovery is ⅓ of a character's stamina. As mentioned, any character can spend a Recovery on their turn, but some abilities let you spend more than one or let others spend their own Recoveries. It’s the one resource that depletes, putting players in a sort of “push your luck” mechanic of balancing having a fat stack of Victories at the start of combat or being fresh on Recoveries.

Another example is the dying mechanic. There’s no unconsciousness and no death saving throws here. A dying player doesn’t actually die until they hit a negative stamina equal to half their stamina value. Instead, once their stamina is negativethey start bleeding and can’t heal themselves like normal, taking more damage every time they do a main action. Maybe they fall back and get help, maybe they go down swinging. Either way, they do it on their feet.

Draw Steel is a very tactical game, and as such, it is not designed for theater of the mind; a battle map is pretty much a requirement. Movement and positioning are important, and the team works together to get everyone where they need to be. Characters and monsters are constantly being kicked, thrown, shoved, and tossed. This isn’t just for funny effects. If they hit something and can’t move, the excess movement becomes damage to both the creature being moved and whatever it hits. Crates get shattered, pillars are broken, bandits go flying like bowling pins, walls get new doorways, and this is always bad for the poor thing crashing into them.

Now, in other games, this level of tactical planning can be a slog. For example, I’m sure we’ve all seen instances where a character ends up a few squares short of being able to do anything meaningful. I have not seen that in Draw Steel. Most of the classes that need to close the distance quickly are quick themselves. In addition to base movement, you have maneuvers and even some main actions that can add more movement. Even at level 1, every character has many options at their disposal, including a ranged attack, and at least one will be a solid choice.

Additionally, there is a lot of synergy at the table. Initiative isn’t fixed; it just passes between the players and the director. So people are always plotting when it makes sense for them to take their turn. Even when it is your turn, it doesn’t mean you are acting alone. Others can use triggered actions or buffs to help out with whatever you might be planning. And just because it’s not your turn does not mean you aren’t doing something. Multiple abilities exist to let other players take various actions off-turn, and everyone is waiting for when a trigger or some other ability might come into play. The action is filled with dramatic moments and rapid shifts in fortune. Players can be up on one turn and severely beaten down the next, only to bounce back with a vengeance, unleashing those high cost Heroic Abilities and some smart teamwork.

Where does all this happen? Well, Draw Steel has its own fantasy setting, but it’s not like what we’ve gotten used to. Over the last few decades, fantasy has sort of genericized into vaguely Tolkien-esque worlds. Not here. This is old school fantasy, the weird stuff. Sure, there’s elves and dwarves and orcs and dragons, and if that is all you want then the setting can accommodate. It’s ready to get wild though, with psionics, people living on the sun, and four-armed alien pirates who sail between planets in magic starships.

The Book

With all that groundwork laid, it’s time to dig into the book itself. Aside from a few pages on terminology and some lore stuff, Draw Steel: Heroes spends over 200 pages (and over half its entire length) just focused on character things. The bulk of those pages are for the classes and their abilities. Classes get a ton of ability options. The rest are for ancestries, backgrounds, kits, perks, and complications.

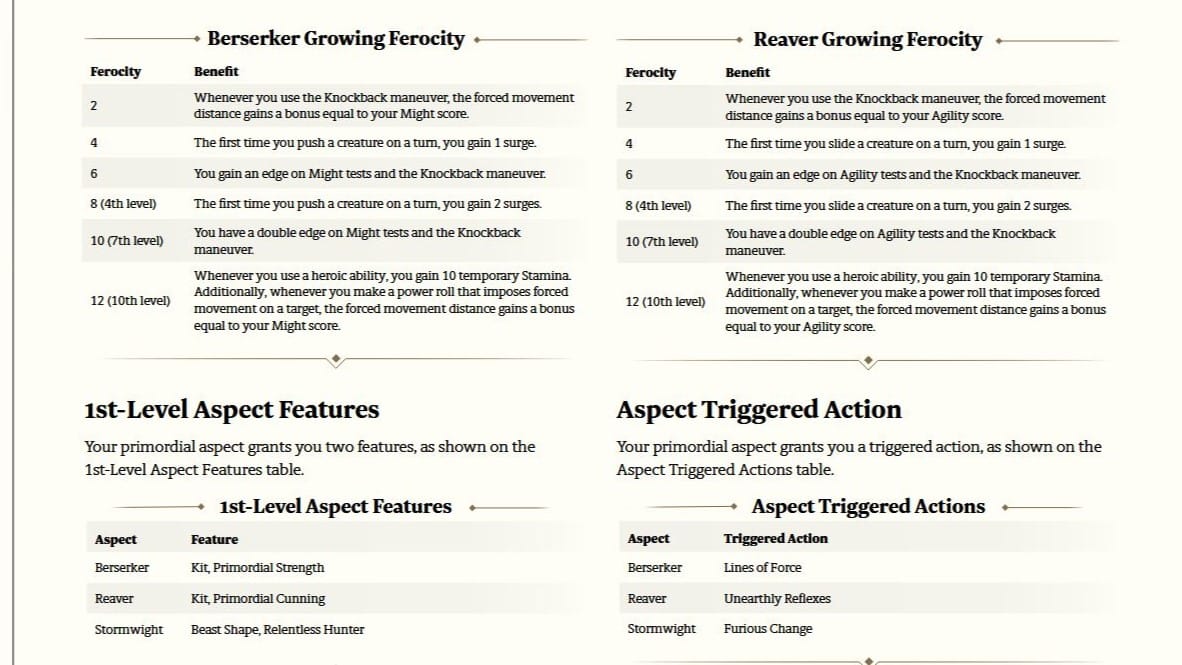

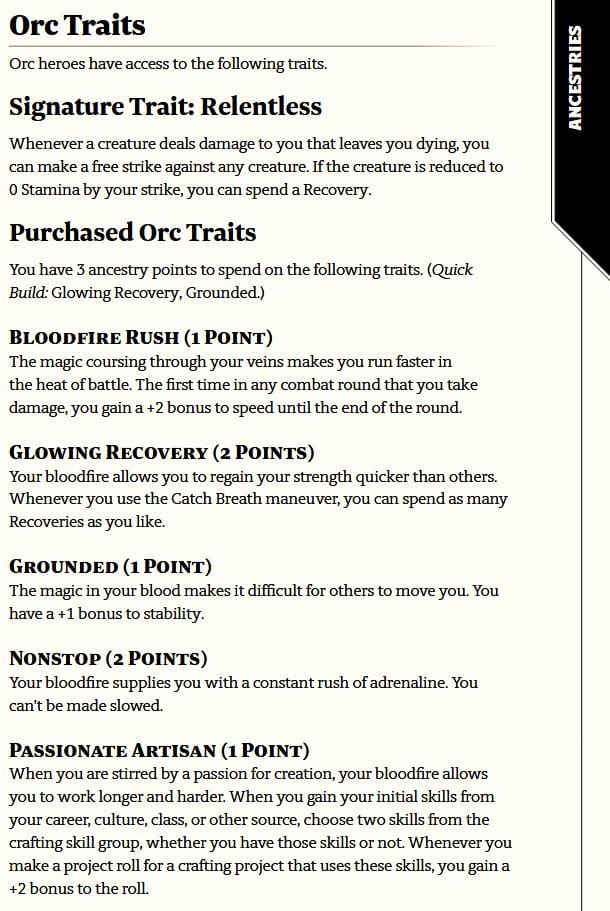

Each ancestry has signature traits and multiple unique trait options on a point buy system. So, every Orc will have “Relentless” but not all will have “Bloodfire Rush”. Backgrounds are split into cultures and careers, and those grant skill group options, languages, perks, and/or other bonuses.

Kits are how Draw Steel does equipment and are usually reserved for the more martial classes. Instead of specific pieces of gear, a kit more defines how a character fights. Each kit uses keywords for a weapon grouping, an armor grouping, a signature ability unique to that kit, and bonuses to movement, stability, damage, range, and stamina. So, the Shining Armor kit means heavy armor, a shield, and a medium weapon, while the Ranger kit wears medium armor, a bow, and a medium weapon. Each of these grouping keywords is given some examples, but it’s a cosmetic decision by the player; the kit itself determines the stats. There’s also nothing locking a character to a kit; they can change it if something isn’t working or they want to experiment.

The Classes chapter actually opens with a good bit of rules explanation. I suppose it’s hard to pick abilities if you don’t know what they mean. Terms are defined, movement rules explained, and areas-of-effect are given full color diagrams. A fundamental aspect of Draw Steel is that it operates on keywords. Every ability will have various keywords associated with it, and those determine how it interacts and is interacted with. All those words have to be defined. It’s essential stuff, but it is presented rather dryly. This is in stark contrast to how most of the rest of the game is presented.

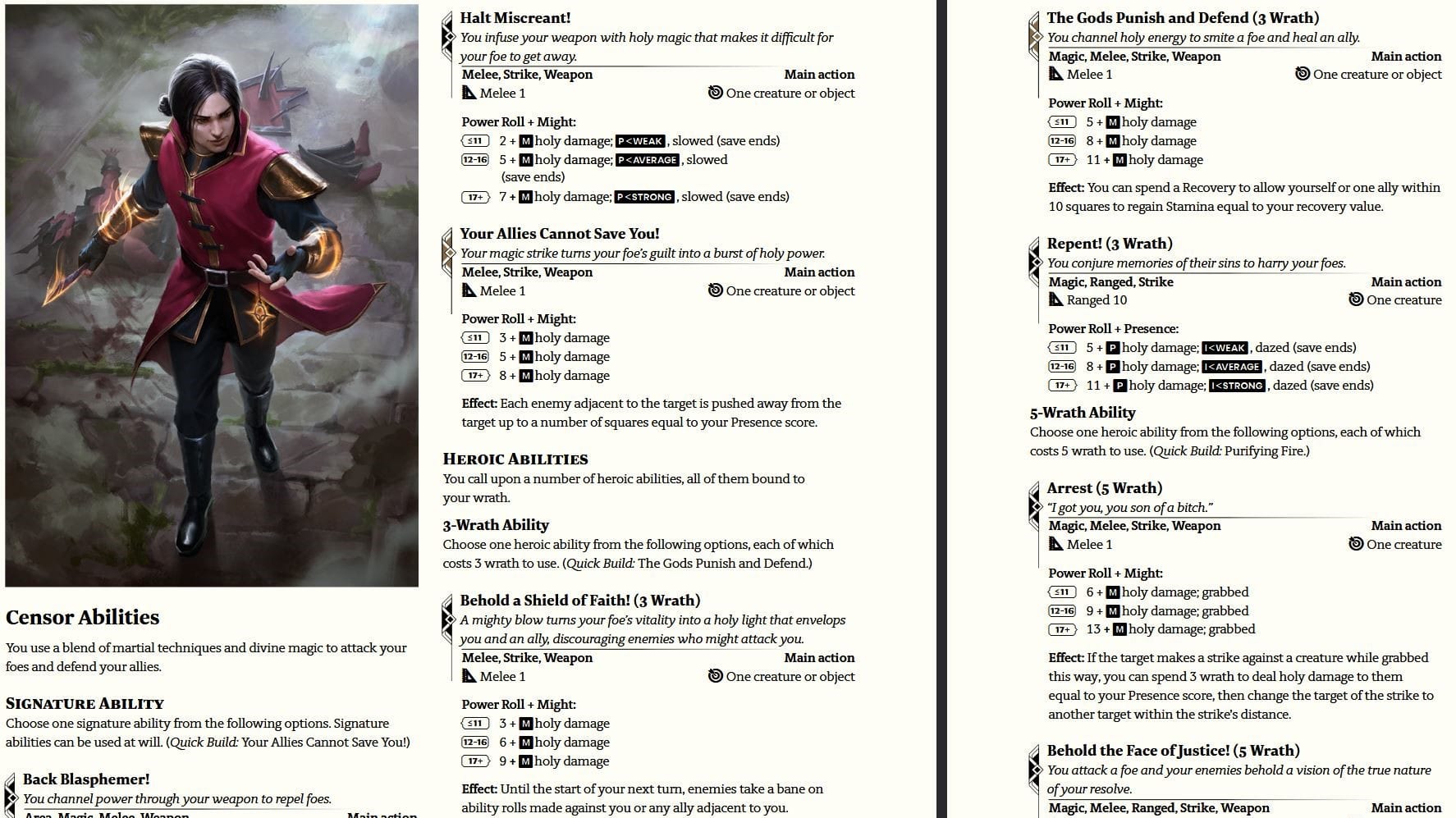

From there, it goes into specific classes. Heroes comes with nine classes, and most are roughly analogous to classes you’re probably familiar with. Each class has at least three subclasses, and, depending on the class and subclass, the analogy may not hold. All of this is just part of your Level One choices. Most classes will have a few things that come automatically from a subclass, and then will have to choose some additional Signature Abilities, a three-point and a five-point Heroic Ability, and any secondary abilities such as a Ward or Blessing.

A hallmark of Draw Steel is how evocative all these powers are. They come with names like “It is Justice You Fear”, “Behold the Mystery”, “Make Peace With Your God”, and “Classic Chandelier Stunt”. These names might not tell you exactly what a power does, but rarely do they disappoint. Many are tongue-in-cheek, and there’s a number of nerd culture references sprinkled around for good measure.

I want to draw special attention to Complications. While technically an optional rule, they are, in my opinion, one of the coolest and most unique things I’ve ever seen for a character option. There are exactly 100 to pick from, and there's even a handy chart if you want to let the dice decide for you. Each complication comes with a unique benefit and a drawback, and in description and effect range from “oh, that’s fun!” to “the writer that came up with this should seek help.”

I won’t spend much time on details, but examples include things like starting with a magic weapon, but it’s cursed. Being a crash-landed astronaut. Starting the game having made a deal with a devil, not to be confused with starting the game having made a deal with a devil without consulting a lawyer before signing. Yes, both are options. Or having your character actually be a sapient fungus that is animating a corpse. My personal favorite is having your head stolen by a magic giant but somehow not dying, so the only way you can see and talk is by psychically sharing other people's heads. Some are considerably less fantastical than these, but all are highly thematic and can give your character a ton of flavor.

Once you've passed the Complications chapter, you’ve finally moved beyond character creation and class specific things. It’s here, about halfway through the book, that the game’s rules start to be explained in detail. There’s a section on how ability tests work, and that includes an explanation of the Montage tests. Montages in Draw Steel are a sort of group check, explained and set up mechanically to work with how individual characters might contribute to the group check. They often require two rolls from each contributing character, with results checked, situations updated, and new ideas from the players needed to advance to the next roll. A solid blend of roleplay and mechanics without getting too bogged down by either.

Given what I’ve described above, you might think the Combat chapter is huge, but it’s actually only about fifteen pages long. There is a lot going on in combat here, but by the time you’ve reached this chapter, most of the specific terms have been defined. It’s a bunch of stuff, but none of it is particularly complicated in the fundamentals, and the rules here just put it all together. Overall, a simple and straightforward chapter.

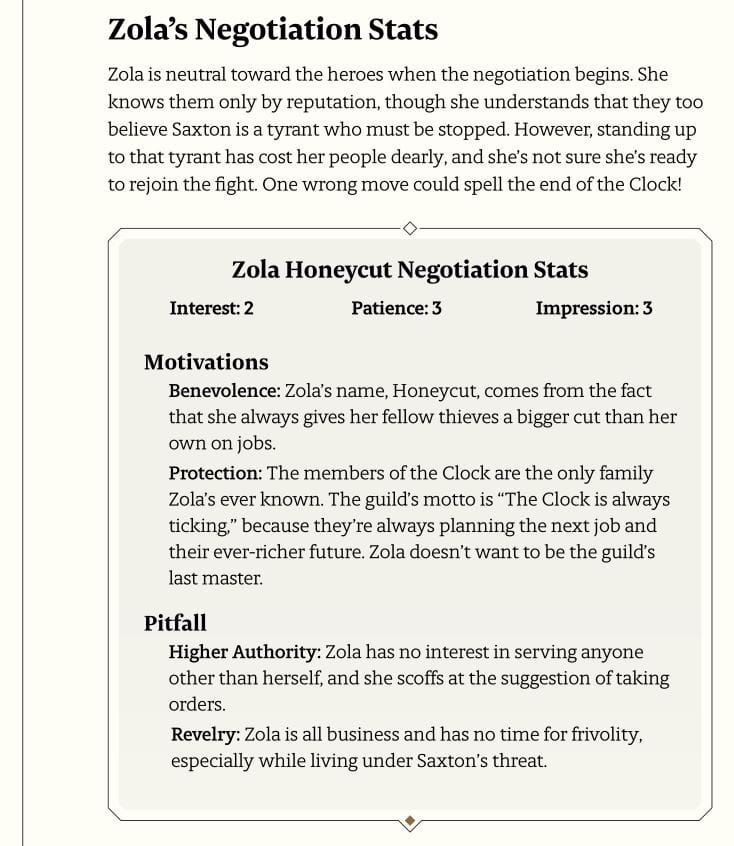

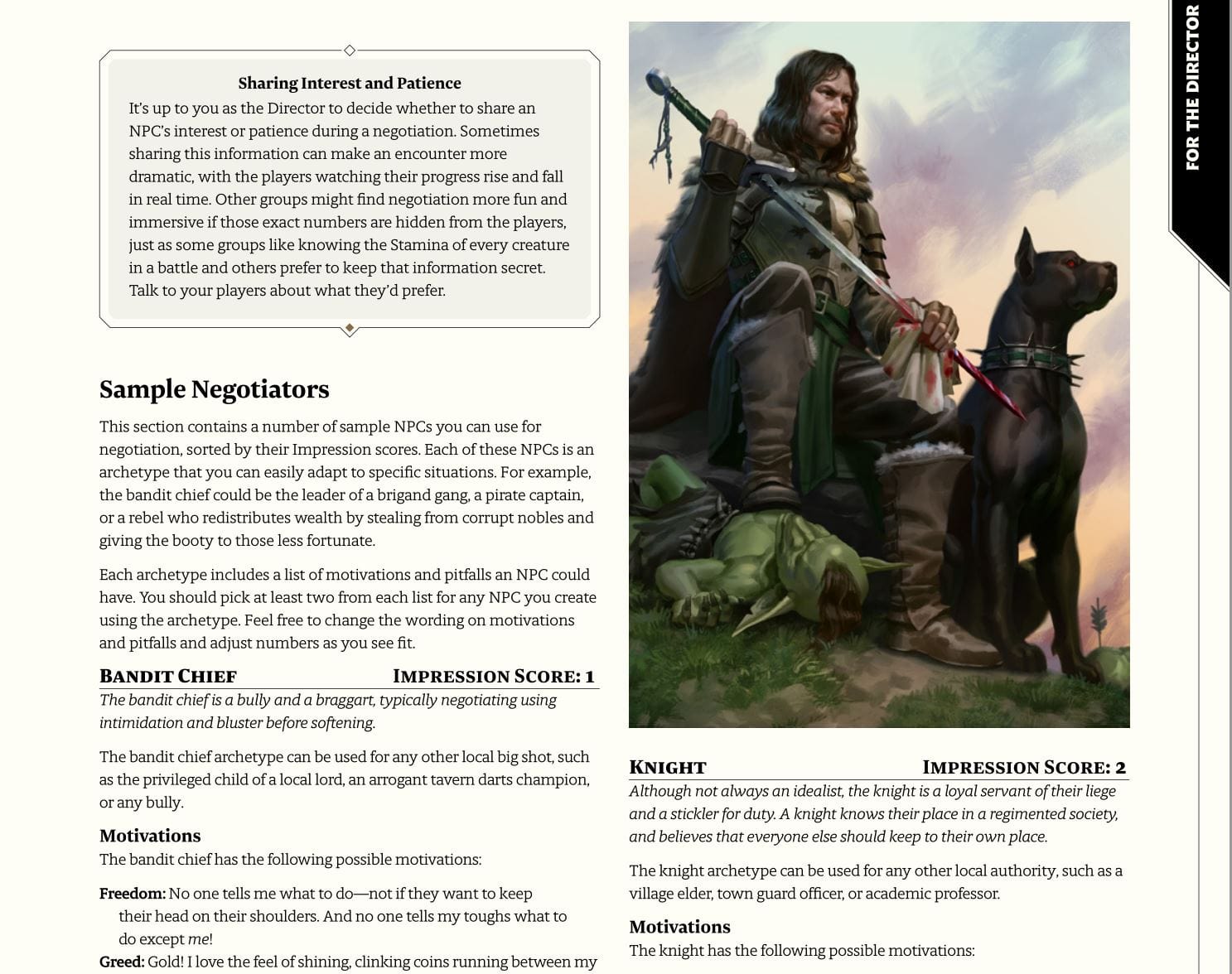

The next chapter brings us to a new type of gameplay: Negotiation. If you’ve played RPGs long enough you’ve seen times when the players haven’t quite gotten what they wanted from roleplaying a negotiation with an NPC, but they have gotten all that NPC is really willing to give up. The gamemaster might not want to end things while the players are still coming up with ideas, but pretty soon those ideas start going in circles. You end up with no clear signal that a conversation has gone as far as it’s going to, so the talking at the table still continues until the GM just has to cut it off. As with montage tests, negotiations are Draw Steel’s way of adding some gameplay elements to these situations without removing the roleplaying elements.

The system has some depth to it, creating stats for the negotiation that include Interest, Patience, Motivations, and Pitfalls. Characters pitch ideas with the goal to reach some kind of agreement before the NPC runs out of Patience or loses Interest. The easiest way for players to do that is to play to the NPC’s Motivations while avoiding their Pitfalls. It’s not purely mechanical either; it may be that the players have nothing to offer that motivates the NPC, which can make for really tough negotiations. Players may use various skills, abilities, roleplay, or other things to try and suss out motivations and pitfalls before a pitch.

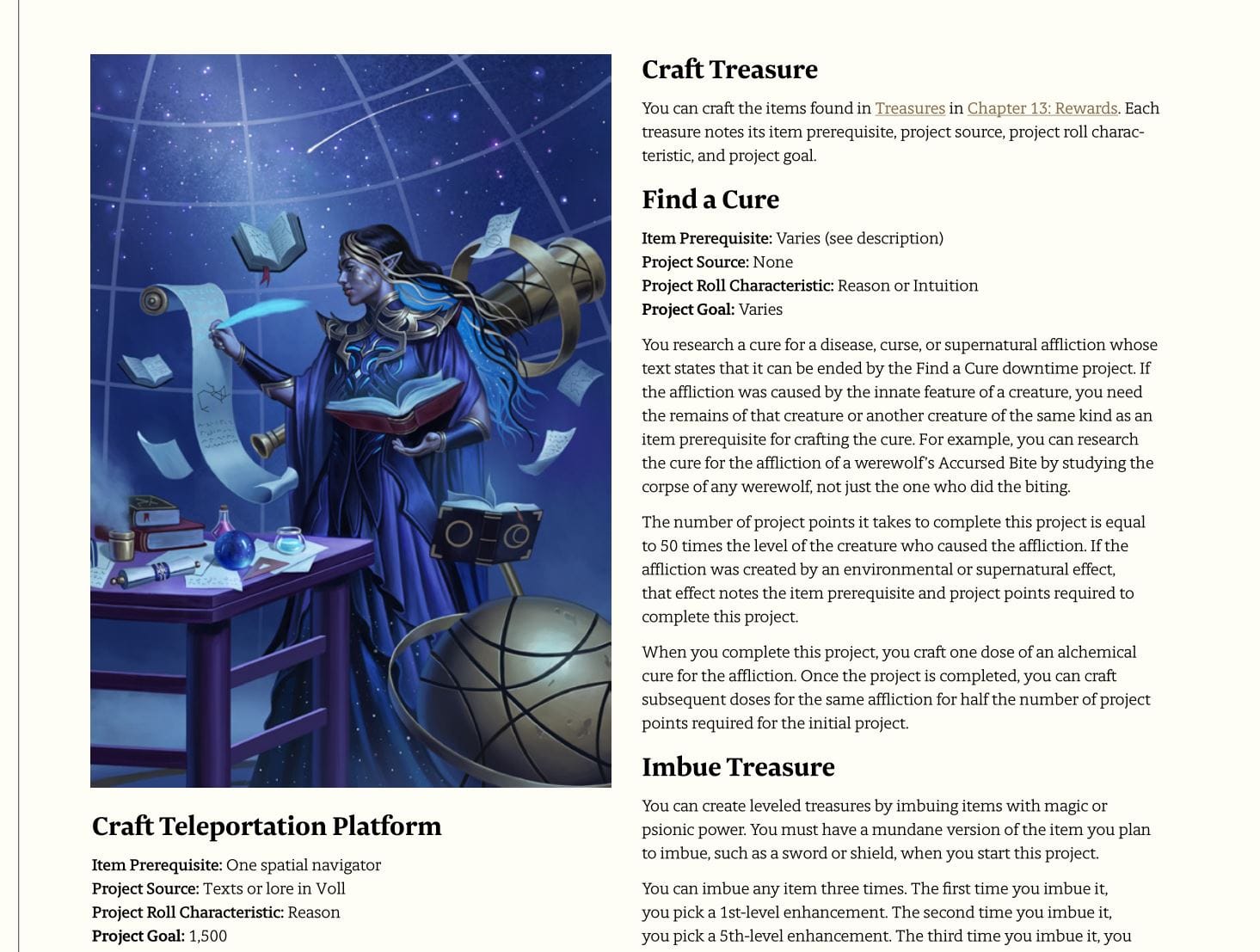

The last chapter of player rules is for Downtime Projects. These are undertaken by a character during a Respite and range from things like crafting magic items or building an airship to something as simple as going fishing. Each has its own requirements, prerequisites, and required materials, and each has a Project Points cost. Any player can undertake any project they meet the requirements for, or assist others in their projects. Rolls are made, and those results go into the Project Points total until the project is complete. Very few things are finished in one roll…it’s unlikely someone can build an airship in a day. There’s enough variety that there’s always something a player should be working on. Overall, a fun aspect of the game.

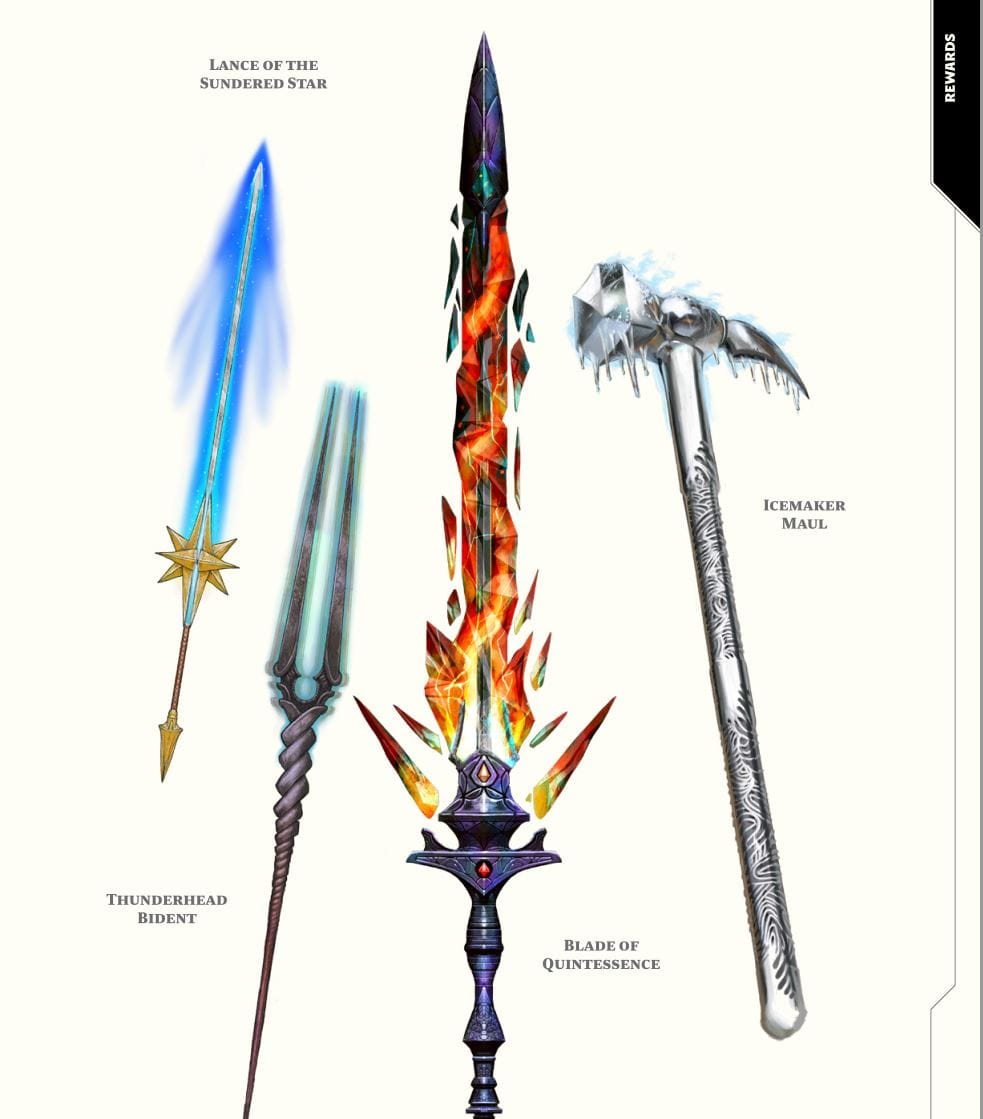

From here, the book goes into various rewards for players. Long before Draw Steel, Matt Colville had stated that players should be aware of what magical items and other bonuses exist, so they can strive toward them. Given the opportunity to do it himself, he did not let it pass by. Rewards primarily come in two forms: treasures and titles. Virtually all of them are usable by any character, though some are a better fit for certain types than others.

Treasures are items, often magical, that the players can equip or use. Some are consumables, such as a healing potion. Since these potions are one of the limited ways to get a recovery without spending one, they’re incredibly valuable to players. Others are items that have a small permanent benefit, called a trinket. These will give things like a damage reduction to a specific damage type, a bonus to abilities that have certain keywords, or other similar situational benefits.

The third type, leveled treasures, come with an interesting twist. These gain strength with their owner, unlocking new effects or bigger bonuses when the character reaches 5th and 9th level. These items are the ones most like the magic items you might be used to, including magic weapons and armor. Ever have the issue of “it’s a nice weapon, but I can’t use longswords” come up? Well, here they operate off the kit keyword groupings, which means if your kit can equip it, so can you. And if your current kit can’t, you can just change it.

All of these categories of items come with a formula for use in the downtime projects system. This means players don’t have to wait and get lucky; they are free to make whatever magic items they want in a downtime project as long as they know how. Don’t know how? Well, that’s its own downtime project. The systems synergize well.

Titles are something I’ve not seen in other games. They are able to be bestowed on characters who’ve completed some specific deed. Despite not actually being a physical item, they can carry considerable bonuses as strong as or stronger than magic items. Typically, these bonuses are reserved for the kind of circumstances in which it was gained. Most present the player with a choice of what bonus is gained, but all will be thematic to that area. For example, all the Zombie Slayer title options are useful against undead, but the title requires defeating a very powerful undead before it can be rewarded. If and when these titles are given out is up to the Director, but it’s an interesting alternative to just more magic items.

The last two types of rewards are Renown and Wealth. Renown reflects how famous a character is. This can have impacts on negotiations but is mostly used for managing followers. Famous characters can gain strongholds and be joined by npcs who will craft, research, or even fight for you. Wealth is used as an abstract system; if things are in your wealth range, you can just buy them. After all, haggling for a few coppers is hardly heroic, and real heroes aren’t in this for the money. Wealth can be increased by things like slaying a dragon and taking its hoard, or by being granted lands or property by grateful monarchs.

The next chapter is on religion in the baseline setting for Draw Steel. This can be of special interest to players of the religious classes, the Censor and the Conduit. There’s some great lore info and it’s well done, but there’s no need to do a deep dive here.

The final chapter is the Director’s. It goes into various aspects of game mastering, planning a campaign, dealing with issues between players, how to run an NPC, and so on. This advice has had some fifty years worth of refinement, and it shows here. It is concise, thorough, and well done.

Montages and Negotiations, being a new kind of system to the genre, are given special attention with detail on how they work from the DM’s side. This includes a suite of Negotiation “stat blocks” to serve as examples of types of NPCs and how they might work at different levels of play. Noticeable in its absence is anything concerning running or creating monsters. All of that information is reserved for the Draw Steel: Monsters book.

Each physical copy sold by MCDM comes with a pdf. As far as the book, I only have a few comments. The quality of binding is high and the book is solid with a nice shiny cover of a giant battle panorama. Very on-brand. A sewn-in ribbon would have been a welcome addition, but not having one is not unusual nor an expectation. As with other MCDM products, the artwork is top tier and each class gets a nice full-page scene. The rest of the book has a bit less art than is typical from them, and I would speculate that this was due to the size of the book. At 400 pages, it’s their largest book, and it has a mountain of info it needs to get out.

Counterpoints

I’ve said a lot of positives about the game so far, but the system isn’t perfect. No system is. So here are some negatives to consider.

The biggest hurdle I think most players will have is just getting started in the game. For someone completely new to Draw Steel, it’s a marathon of decision making. You pick your ancestry and then spend your ancestry points. You build a culture which is made up of three subtypes and each subtype grants a skill from one of the different skill groups. Then you pick a career, which comes with more skills, languages, perks, and an inciting incident. All of this can easily take over an hour if you read through every choice, and you haven’t even picked a class yet!

This is compounded by many of these things not being on the same pages or even the same sections, so a whole lot of book flipping or pdf scrolling is required. The game had many months of updated playtesting with feedback from the community. I’m sure MCDM had a ton of data for editing and layout when they arranged the pages, so I don’t fault them; the arrangement is likely about as optimized as it’s possible to be. The nature of having so many choices simply makes it impossible to put everything someone needs into as easy reach as we’d like it to be.

Of course, players still aren’t done! Now you pick your class. And once you have a class, then it’s on to subclass, signature abilities, heroic abilities, and kits or whatever else your class has going on. With all this new stuff, it’s a lot to throw at even veteran players.

Fortunately, due to Draw Steel’s very permissive licensing, there are already a number of free online tools to help make getting through these steps easier. The character building process is so involved that I can’t recommend that someone make their first character without using some kind of available tool. All of this said, by the time you’ve gone through all those steps, you will thoroughly know this character. The backstory and a sense of “who is this person” is there before you even finish.

In the same vein, the first few combats are going to be a mess. While the systems in play and the rolling mechanics are straightforward, there’s just a lot of things going on. Every round, a player gets a trigger, and on their turn there’s a main action, movement, and a maneuver. Some things, or some abilities, are free, so you might end up doing more than one of any of those. The stack of terminology is large, and everything has its own meaning. A Shift is different from a Slide, which is different from a Push, and a Surge is different from an Edge, and so on. It took us several sessions for everyone to get used to their characters and how they work. Even so, we still get to the end of a round and someone (often me) says “Oh, I forgot to use my trigger.”

I have a few other minor quibbles. There’s a color coded tab on the pages to let you know which chapter you’re on. With almost ⅓ of the entire book being on classes, having the entire classes section be one color feels like a missed chance to make all the page flipping a little better.

My other complaint is with Edges and Double Edges and Banes and Double Banes. An Edge grants a character +2 on a roll, but a Double Edge adds nothing and instead grants a result one tier higher than what is actually rolled. Banes are the same, just inverted. Simple enough. So what’s my issue? Well, for every other system in the game, mechanics that do something differently get a different name. All other mechanics flow into each other in a way that ends up being intuitive. Edges and Banes are the only mechanics that “double” like that, but having the double versions be different from the base versions just feels a little jarring when everything else flows so smoothly. Of course, having two more terms to memorize is maybe not the simpler option either. Again, it’s minor, but it is one of those things that my brain doesn’t want to let go of.

Conclusion

Time to stop picking nits and put all of this together. If you’ve made it this far, you may have realized that I’m enamored with this system. I’ve been basically burned out on fantasy TTRPGs for almost a year, but Draw Steel has me counting the days to the next session. Yes, creating that first character and getting through that first battle can be rough. It doesn’t take long until things start flowing smoothly, though.

It can be difficult to convey how much fun the combat is when it’s firing on all cylinders. Battles against solo monsters keep the whole party on the edge of their seat. Smashing through hordes of minions puts big dumb grins on everyone’s faces. Some of the people I’m playing with are very much not the tactical combat types, but even they get into the groove and can’t wait to drop that big, gaming changing ability. The fun is infectious.

Draw Steel: Heroes

Excellent

Draw Steel: Heroes has redefined what TTRPG combat can be and how much fun can be had. This is the book to get you started on your new adventures.

Pros

- Rewarding, high-octane action combat

- Tons of character depth without being overly complex

- Doesn’t shirk the non-combat pillars of play even if they can get overshadowed

Cons

- Lengthy list of character options means a lengthy creation process

- New system has so many things happening that it will take time to adjust

This review is based on a copy provided by GamingTrend.

Be sure to check out our review of the other Draw Steel core book:

Draw Steel: Monsters review